7.3 Job Design

A fundamental aspect of designing an organization is how to assign jobs to individual contributors.

Job Design

Many of us assume that the most important motivator at work would be pay. Yet, studies point to a different factor as the major influence over worker motivation: Job design. How a job is designed has a major impact on employee motivation, job satisfaction, commitment to organization, as well as absenteeism and turnover. Job design is just one of the many organizational design decisions managers must make when engaged in the organizing function.

The question of how to properly design jobs so that employees are more productive and more satisfied has received managerial and research attention since the beginning of the 20th century.

Scientific Management and Job Specialization

Perhaps the earliest attempt to design jobs was presented by Frederick Taylor in his 1911 book Principles of Scientific Management. Scientific management proposed a number of ideas that have been influential in job design. One idea was to minimize waste by identifying the best method to perform the job to ensure maximum efficiency. Another one of the major advances of scientific management was job specialization, which entails breaking down tasks to their simplest components and assigning them to employees so that each person would perform few tasks in a repetitive manner. While this technique may be very efficient in terms of automation and standardization, from a motivational perspective, these jobs will be boring and repetitive and therefore associated with negative outcomes such as absenteeism (Campion & Thayer, 1987). Job specialization is also an ineffective way of organizing jobs in rapidly changing environments where employees close to the problem should modify their approach based on the demands of the situation (Wilson, 1999).

Rotation, Job Enlargement, and Enrichment

One of the early alternatives to job specialization was job rotation, which involves moving employees from job to job at regular intervals, thereby relieving the monotony and boredom typical in repetitive jobs. For example, Maids International, a company that provides cleaning services to households and businesses, uses job rotation such that maids cleaning the kitchen in one house would clean the bedroom in another house (Denton, 1994). Using this technique, among others, the company was able to reduce its turnover level. In a study conducted in a supermarket, cashiers were rotated to work in different departments. As a result of the rotation, employee stress level was reduced as measured by their blood pressure. Moreover, they reported fewer pain symptoms in their neck and shoulders (Rissen, et. al., 2002).

Job rotation has a number of advantages for organizations. It is an effective way for employees to acquire new skills, as the rotation involves cross-training to new tasks; this means that organizations increase the overall skill level of their employees (Campion, et. al., 1994). In addition, job rotation is a means of knowledge transfer between departments (Kane, et. al., 2005). For the employees, rotation is a benefit because they acquire new skills, which keeps them marketable in the long run.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that companies successfully rotate high-level employees to train their managers and increase innovativeness in the company. For example, Nokia uses rotation at all levels, such as assigning lawyers to act as country managers or moving network engineers to handset design. These approaches are thought to bring a fresh perspective to old problems (Wylie, 2003). India’s information technology giant Wipro, which employs about 80,000 employees, uses a 3-year plan to groom future leaders of the company by rotating them through different jobs (Ramamurti, 2001).

Job enlargement refers to expanding the tasks performed by employees to add more variety. Like job rotation, job enlargement can reduce boredom and monotony as well as use human resources more effectively. When jobs are enlarged, employees view themselves as being capable of performing a broader set of tasks (Parker, 1998). Job enlargement is positively related to employee satisfaction and higher-quality customer services, and it increases the chances of catching mistakes (Campion & McClelland, 1991). At the same time, the effects of job enlargement may depend on the type of enlargement. For example, exclusively giving employees simpler tasks had negative consequences on employee satisfaction with the job of catching errors, whereas giving employees more tasks that require them to be knowledgeable in different areas seemed to have more positive effects (Campion & McClelland, 1993).

Job enrichment is a job redesign technique that allows workers more control over how they perform their own tasks, giving them more responsibility. As an alternative to job specialization, companies using job enrichment may experience positive outcomes such as reduced turnover, increased productivity, and reduced absences (McEvoy & Cascio, 1985; Locke, et. al., 1976). This may be because employees who have the authority and responsibility over their own work can be more efficient, eliminate unnecessary tasks, take shortcuts, and overall increase their own performance. At the same time, there is some evidence that job enrichment may sometimes cause employees to be dissatisfied (Locke, et. al., 1976). The reason may be that employees who are given additional autonomy and responsibility may expect greater levels of pay or other types of compensation, and if this expectation is not met, they may feel frustrated. One more thing to remember is that job enrichment may not be suitable for all employees (Cherrington & Lynn, 1980; Hulin & Blood, 1968). Not all employees desire to have control over how they work, and if they do not have this desire, they may feel dissatisfied in an enriched job.

Job Characteristics Model

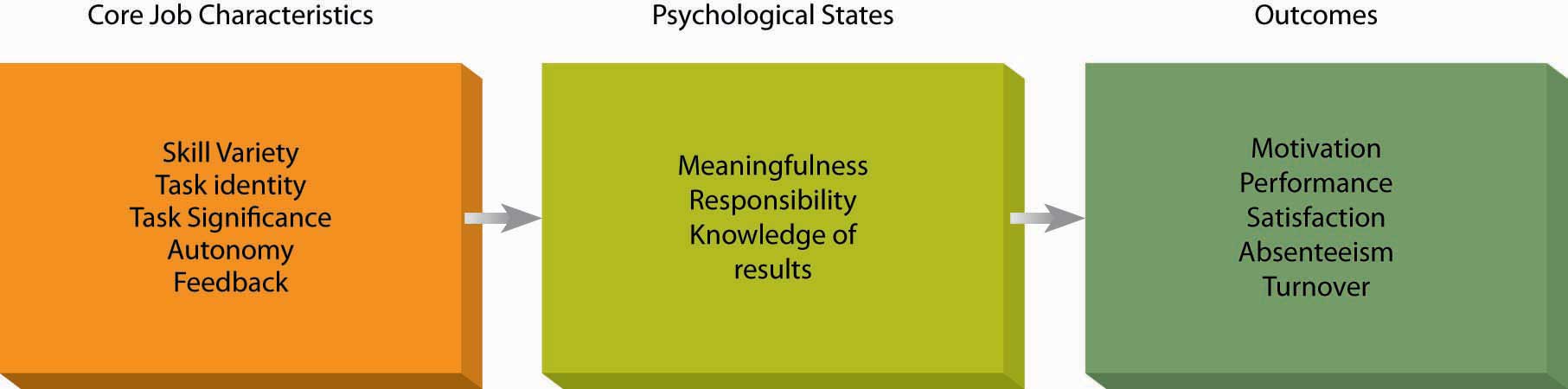

The job characteristics model is one of the most influential attempts to design jobs to increase their motivational properties (Hackman & Oldham, 1975). Proposed in the 1970s by Hackman and Oldham, the model describes five core job dimensions, leading to three critical psychological states, which lead to work-related outcomes. In this model, shown in the following figure, there are five core job dimensions.

Figure 7.3.16 Job Characteristics Model

Adapted from Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1975). Development of the job diagnostic survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60, 159–170.

Skill variety refers to the extent to which the job requires the person to use multiple high-level skills. A car wash employee whose job consists of directing employees into the automated carwash demonstrates low levels of skill variety, whereas a car wash employee who acts as a cashier, maintains carwash equipment, and manages the inventory of chemicals demonstrates high skill variety.

Task identity refers to the degree to which the person completes a piece of work from start to finish. A Web designer who designs parts of a Web site will have low task identity because the work blends in with other Web designers’ work, and in the end, it will be hard for the person to claim responsibility for the final output. The Webmaster who designs the entire Web site will have high task identity.

Task significance refers to whether the person’s job substantially affects other people’s work, health, or well-being. A janitor who cleans the floor at an office building may find the job low in significance, thinking it is not an important job. However, janitors cleaning the floors at a hospital may see their role as essential in helping patients recover in a healthy environment. When they see their tasks as significant, employees tend to feel that they are making an impact on their environment and their feelings of self worth are boosted (Grant, 2008).

Autonomy is the degree to which the person has the freedom to decide how to perform tasks. As an example, a teacher who is required to follow a predetermined textbook, cover a given list of topics, and use a specified list of classroom activities has low autonomy, whereas a teacher who is free to choose the textbook, design the course content, and use any materials she sees fit has higher levels of autonomy. Autonomy increases motivation at work, but it also has other benefits. Autonomous workers are less likely to adopt a “this is not my job” attitude and instead be proactive and creative (Morgeson, et. al., 2005; Parker, et. al., 1997; Parker, et. al., 2006; Zhou, 1998). Giving employees autonomy is also a great way to train them on the job. For example, Gucci’s CEO Robert Polet describes autonomy he received while working at Unilever as the key to his development of leadership talents (Gumbel, 2008).

Feedback refers to the degree to which the person learns how effective he or she is at work. Feedback may come from other people such as supervisors, peers, subordinates, customers, or from the job. A salesperson who makes informational presentations to potential clients but is not informed whether they sign up has low feedback. If this salesperson receives a notification whenever someone who has heard his presentation becomes a client, feedback will be high.

The mere presence of feedback is not sufficient for employees to feel motivated to perform better, however. In fact, in about one-third of the cases, feedback was detrimental to performance (Kluger & DeNisi, 1996). In addition to whether feedback is present, the character of the feedback (positive or negative), whether the person is ready to receive the feedback, and the manner in which feedback was given will all determine whether employees feel motivated or demotivated as a result of feedback.