8.8 Employee Performance Evaluation

Learning Objectives

- Understand where goals and objectives fit in employee development.

- See how goals and objectives are part of an effective employee performance evaluation process.

Goals, Objectives, and Performance Reviews

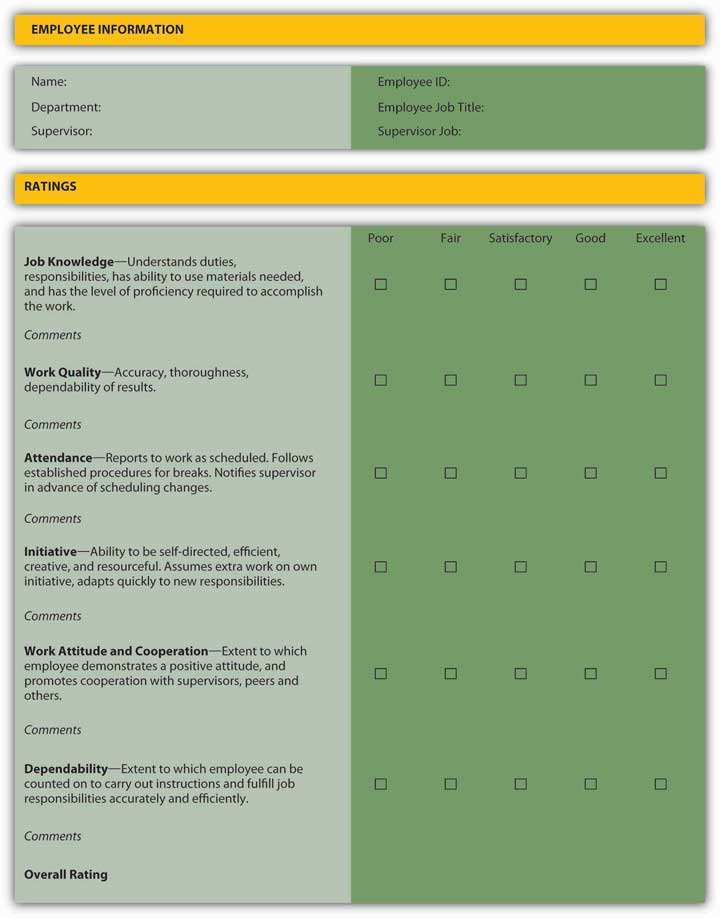

Since leadership is tasked with accomplishing things through the efforts of others, an important part of your principles of management tool kit is the development and performance evaluation of people. A performance evaluation is a constructive process to acknowledge an employee’s performance. Goals and objectives are a critical component of effective performance evaluations, so we need to cover the relationship among them briefly in this section. For instance, the example evaluation form needs to have a set of measurable goals and objectives spelled out for each area. Some of these, such as attendance, are more easy to describe and quantify than others, such as knowledge. Moreover, research suggests that individual and organizational performance increase 16% when an evaluation system based on specific goals and objectives is implemented (Rynes, et. al., 2002).

Role and Limitations of Performance Evaluations

Most organizations conduct employee performance evaluations at least once a year, but they can occur more frequently when there is a clear rationale for doing so—for instance, at the end of a project, at the end of each month, and so on. For example, McKinsey, a leading strategy consulting firm, has managers evaluate employees at the end of every consulting engagement. So, in addition to the annual performance evaluation, consultants can receive up to 20 mini-evaluations in a year. Importantly, the timing should coincide with the needs of the organization and the development needs of the employee.

Figure 8.10

Performance evaluation based on clear goals and objectives leaves little doubt about the desired outcome.

Pixabay – CC0 public domain.

Performance evaluations are critical. Organizations are hard-pressed to find good reasons why they can’t dedicate an hour-long meeting at least once a year to ensure the mutual needs of the employee and organization are being met. Performance reviews help managers feel more honest in their relationships with their subordinates and feel better about themselves in their supervisory roles. Subordinates are assured clear understanding of what goals and objectives are expected from them, their own personal strengths and areas for development, and a solid sense of their relationship with their supervisor. Avoiding performance issues ultimately decreases morale, decreases credibility of management, decreases the organization’s overall effectiveness, and wastes more of management’s time to do what isn’t being done properly.

Finally, it is important to recognize that performance evaluations are a not a panacea for individual and organizational performance problems. Studies show that performance-appraisal errors are extremely difficult to eliminate (Rynes, et. al., 2002). Training to eliminate certain types of errors often introduces other types of errors and sometimes reduces accuracy. The most common appraisal error is leniency, and managers often realize they are committing it. Mere training is insufficient to eliminate these kinds of errors: action that is more systematic is required, such as intensive monitoring or forced rankings.

Another potential error a manager may make is called the “halo effect”. This is the concept that a manager may look at one positive attribute of an employee and generalize that to believe that other attributes are also positive. For example, a manager may like a sales person’s interpersonal skills with customers but then overlook that they are poor at record keeping and support of their peers.

Managers may also fall victim to recency error. That occurs when a manager only looks at the most recent performance of an employee and ignores or disregards earlier performance.

An Example of the Performance Review Process

For the purpose of this example, let’s assume that the organization has determined that annual performance evaluations fit the strategic needs of the organization and the developmental needs of employees. This does not mean however that management and employees discuss goals, objectives, and performance only once a year. In our example, the organization has opted to have a midyear information meeting and then an end-of-year performance evaluation meeting.

At some point in the year, the supervisor should hold a formal discussion with each staff member to review individual activities to date and to modify the goals and objectives that employee is accountable for. This agreed-upon set of goals and objectives is sometimes called an employee performance plan. There should be no surprises at this meeting. The supervisor should have been actively involved in continual assessment of his or her staff through regular contact and coaching. If major concerns arise, the performance plan can be modified or the employees can receive development in areas in which they may be weak. This also is a time for the employee to provide formal feedback to the supervisor on the coaching, on the planning, and on how the process seems to be working.

At the end of the year, a final review of the activities and plans for developing the next year’s objectives begin. Again, this is a chance to provide constructive and positive feedback and to address any ongoing concerns about the employee’s activities and competencies. Continuing education opportunities can be identified, and for those systems linked to compensation, salary raises will be linked to the employee’s performance during the year. Again, there should be no surprises to either employee or supervisor, as continual assessment and coaching should take place throughout the year. Supervisors and managers are involved in the same series of activities with their own supervisors to ensure that the entire organization is developing and focused on the same common objectives.

There are many varieties of performance management systems available, but you must be aware that you will need to tailor any system to suit the needs of the organization and the staff. As the organization and its competitive environment change over time, the system will also need to develop to reflect changes to employee competencies, ranking systems, and rewards linked to the plan.

How do you handle your reviews, that is, when you are the focus of the review process? “Your Performance Review” summarizes some key ideas you might keep in mind for your next review.

Your Performance Review

There are typically three areas you should think about when having your own performance reviewed: (1) preparation for the review, (2) what to do if the review is negative, and (3) what should you ultimately take away from the review.

Prepare for an upcoming review. Document your achievements and list anything you want to discuss at the review. If you haven’t kept track of your achievements, you may have to spend some time figuring out what you have accomplished since your last review and, most importantly, how your employer has benefited, such as increased profits, grown the client roster, maintained older clients, and so on. These are easier to document when you have had clear goals and objectives.

What should you do if you get a poor review? If you feel you have received an unfair review, you should consider responding to it. You should first try to discuss the review with the person who prepared it. Heed this warning, however. Wait until you can look at the review objectively. Was the criticism you received really that off the mark or are you just offended that you were criticized in the first place? If you eventually reach the conclusion that the review was truly unjust, then set an appointment to meet with your reviewer. If there are any points that were correct, acknowledge those. Use clear examples that counteract the criticisms made. A paper trail is always helpful. Present anything you have in writing that can back you up. If you didn’t leave a paper trail, remember to do this in the future.

What should you take away from a performance review? Ultimately, you should regard your review as a learning opportunity. For instance, did you have clear goals and objectives such that your performance was easy to document? You should be able to take away valuable information, whether it is about yourself or your reviewer.

Best Practices

While there is no single “best way” to manage performance evaluations, the collective actions across a number of high-performing firms suggests a set of best practices.

- Decide what you are hoping to achieve from the system. Is it to reward the stars and to correct problems? Or is its primary function to be a tool in focusing all staff activities through better planning?

- Develop goals and objectives that inspire, challenge, and stretch people’s capabilities. Once goals and objectives are clearly communicated and accepted, enlist broad participation, and do not shut down ideas. Support participation and goal attainment through the reward system, such as with gainsharing or other group incentive programs.

- Ensure you have commitment from the top. Planning must begin at the executive level and be filtered down through the organization to ensure that employees’ plans are meaningful in the context of the organization’s direction. Top managers should serve as strong role models for the performance evaluation process and attach managerial consequences to the quality of performance reviews (for instance, McKinsey partners are evaluated on how well they develop their consultants, not just the profitability of their particular practice).

- Ensure that all key staff are involved in the development of the performance management processes from the early phases. Provide group orientations to the program to decrease anxiety over the implementation of a new system. It will ensure a consistent message communicated about the performance management system.

- If the performance management system is not linked to salary, be sure employees are aware of it. For example, university business school professors are paid salaries based on highly competitive external labor markets, not necessarily the internal goals and objectives of the school such as high teaching evaluations, and so on. Make sure employees know the purpose of the system and what they get out of it.

- Provide additional training for supervisors on how to conduct the midyear and year-end performance reviews. Ensure that supervisors are proficient at coaching staff. Training, practice, and feedback about how to avoid appraisal errors are necessary, but often insufficient, for eliminating appraisal errors. Eliminating errors may require alternative approaches to evaluation, such as forced distribution (for instance, General Electric must rank the lowest 10% of performers and often ask them to find work with another employer).

- Plan to modify the performance management system over time, starting with goals and objectives, to meet your organization’s changing needs. Wherever possible, study employee behaviors in addition to attitudes; the two do not always converge.

Key Takeaway

This section outlined the relationship between goals and objectives and employee performance evaluation. Performance evaluation is a tool that helps managers align individual performance with organizational goals and objectives. You saw that the tool is most effective when evaluation includes well-developed goals and objectives that are developed with the needs of both the organization and employee in mind. The section concluded with a range of best practices for the performance evaluation process, including the revision of goals and objectives when the needs of the organization change.

Exercises

- How are goals and objectives related to employee performance evaluation?

- How often should performance evaluations be performed?

- What kinds of goals and objectives might be best for performance evaluation to be most effective?

- What should be included in an employee performance plan?

- What performance evaluation best practices appear to most directly involve goals and objectives?

References

Rynes, S., Brown, K., & Colbert, A. 2002. Seven common misconceptions about human resource practices: Research findings versus practitioner beliefs. Academy of Management Executive, 16(3): 92–102.