SEEING YOUR BREATH

Why can you “see your breath” on a cold day? The air you exhale through your nose and mouth is warm like the inside of your body. Exhaled air also contains a lot of water vapor, because it passes over moist surfaces from the lungs to the nose or mouth. The water vapor in your breath cools suddenly when it reaches the much colder outside air. This causes the water vapor to condense into a fog of tiny droplets of liquid water. You release water vapor and other gases from your body through the process of respiration.

WHAT IS RESPIRATION?

Respiration is the life-sustaining process in which gases are exchanged between the body and the outside atmosphere. Specifically, oxygen moves from the outside air into the body; and water vapor, carbon dioxide, and other waste gases move from inside the body to the outside air. Respiration is carried out mainly by the respiratory system. It is important to note that respiration by the respiratory system is not the same process as cellular respiration —which occurs inside cells — although the two processes are closely connected. Cellular respiration is the metabolic process in which cells obtain energy, usually by “burning” glucose in the presence of oxygen. When cellular respiration is aerobic, it uses oxygen and releases carbon dioxide as a waste product. Respiration by the respiratory system supplies the oxygen needed by cells for aerobic cellular respiration and removes the carbon dioxide produced by cells during cellular respiration.

Respiration by the respiratory system actually involves two subsidiary processes. One process is ventilation, or breathing. Ventilation is the physical process of conducting air to and from the lungs. The other process is gas exchange. This is the biochemical process in which oxygen diffuses out of the air and into the blood, while carbon dioxide and other waste gases diffuse out of the blood and into the air. All of the organs of the respiratory system are involved in breathing, but only the lungs are involved in gas exchange.

RESPIRATORY ORGANS

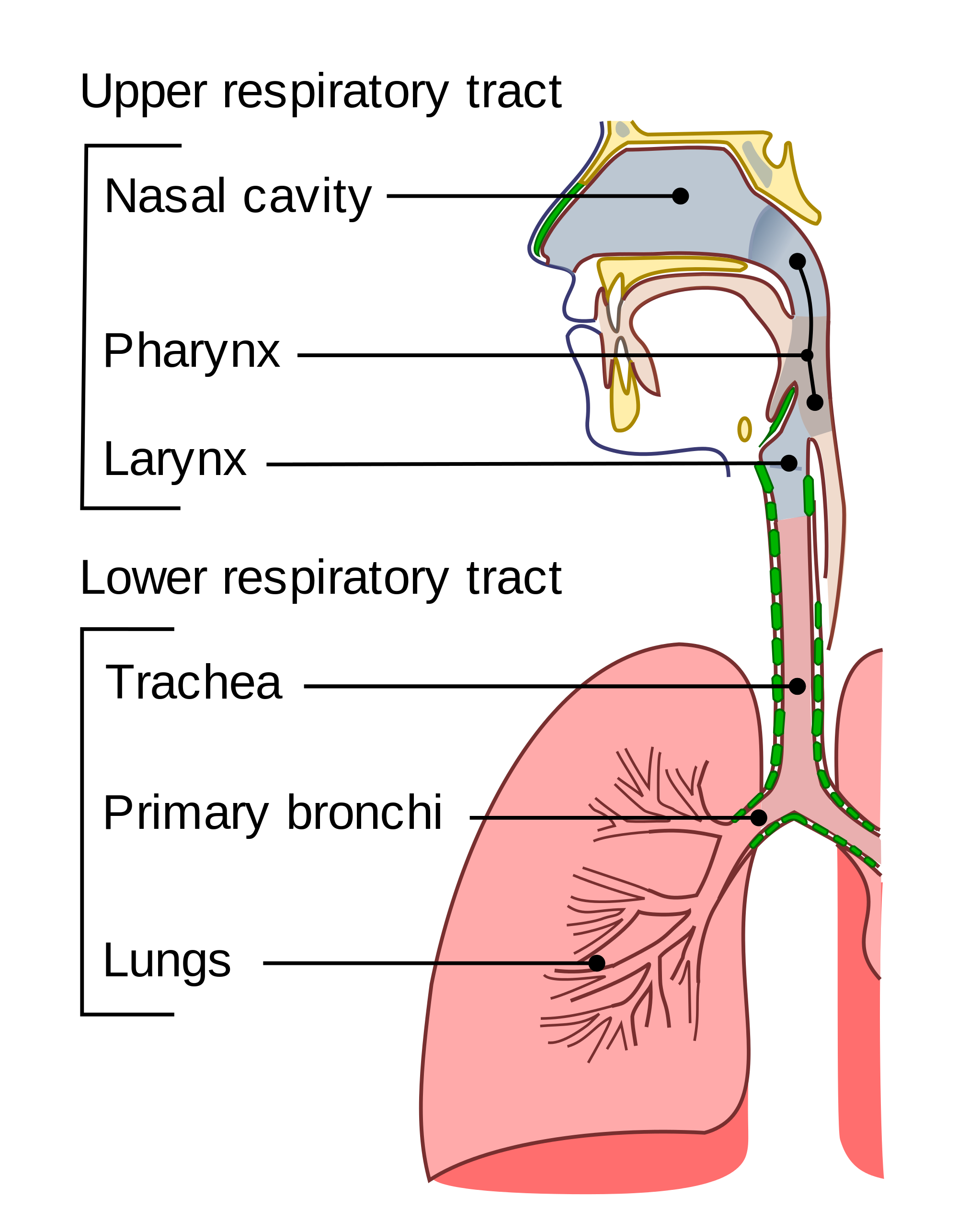

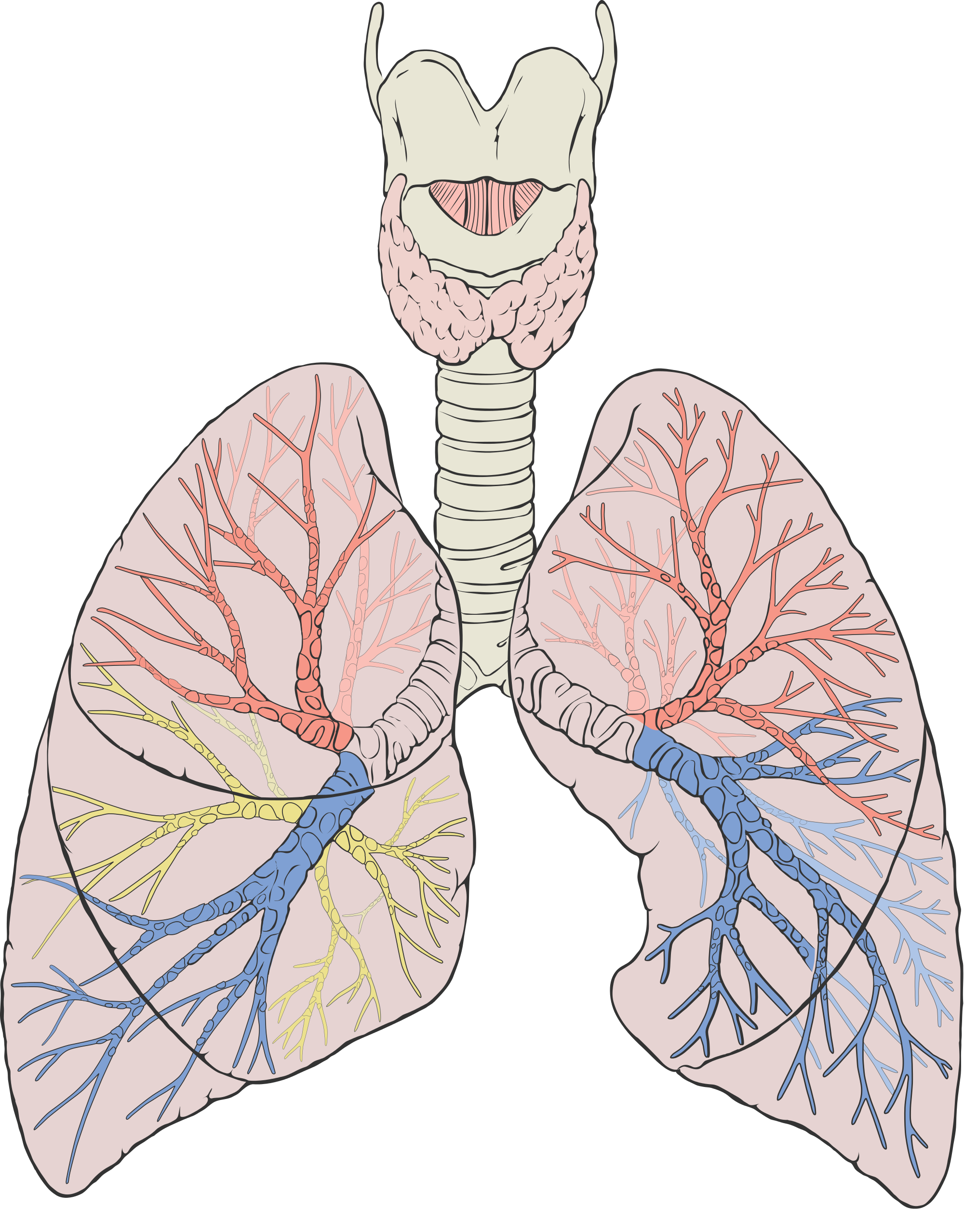

The organs of the respiratory system form a continuous system of passages, called the respiratory tract, through which air flows into and out of the body. The respiratory tract has two major divisions: the upper respiratory tract and the lower respiratory tract. The organs in each division are shown in Figure 12.2. In addition to these organs, certain muscles of the thorax (body cavity that fills the chest) are also involved in respiration by enabling breathing. Most important is a large muscle called the diaphragm, which lies below the lungs and separates the thorax from the abdomen. Smaller muscles between the ribs also play a role in breathing.

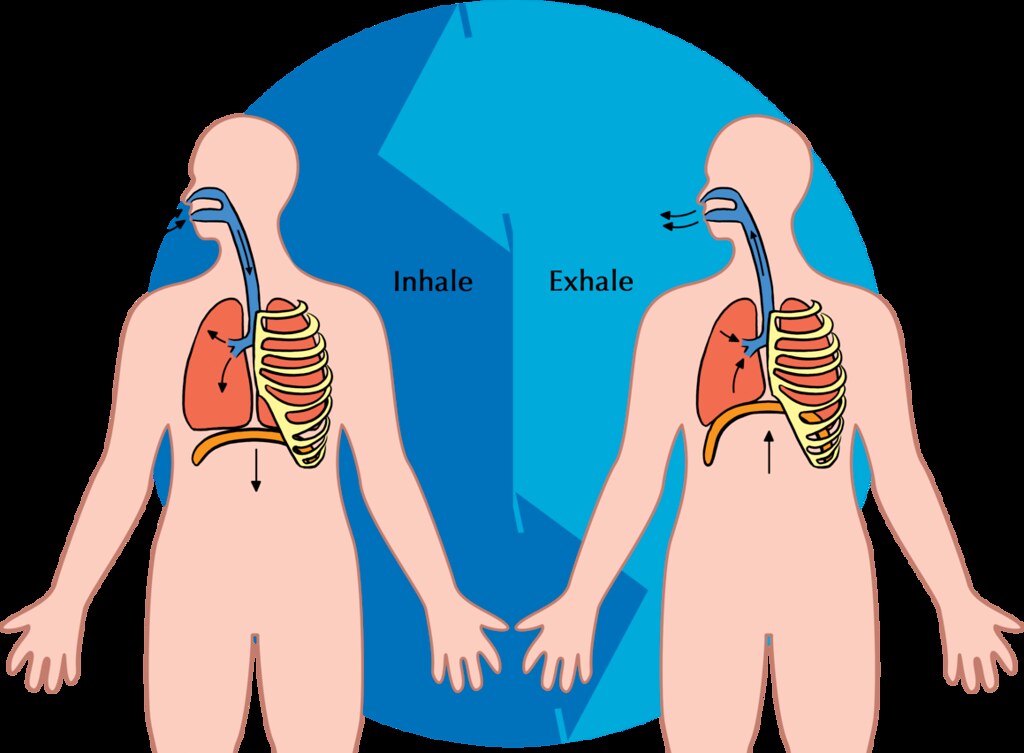

Figure 12.2 During breathing, inhaled air enters the body through the nose and passes through the respiratory tract to the lungs. Exhaled air travels from the lungs in the opposite direction.

Figure 12.2 During breathing, inhaled air enters the body through the nose and passes through the respiratory tract to the lungs. Exhaled air travels from the lungs in the opposite direction.

UPPER RESPIRATORY TRACT

All of the organs and other structures of the upper respiratory tract are involved in conduction, or the movement of air into and out of the body. Upper respiratory tract organs provide a route for air to move between the outside atmosphere and the lungs. They also clean, humidify, and warm the incoming air. No gas exchange occurs in these organs.

Nasal Cavity

The nasal cavity is a large, air-filled space in the skull above and behind the nose in the middle of the face. It is a continuation of the two nostrils. As inhaled air flows through the nasal cavity, it is warmed and humidified by blood vessels very close to the surface of this epithelial tissue. Hairs in the nose and mucous produced by mucous membranes help trap larger foreign particles in the air before they go deeper into the respiratory tract. In addition to its respiratory functions, the nasal cavity also contains chemoreceptors needed for sense of smell, and contribution to the sense of taste.

Pharynx

The pharynx is a tube-like structure that connects the nasal cavity and the back of the mouth to other structures lower in the throat, including the larynx. The pharynx has dual functions — both air and food (or other swallowed substances) pass through it, so it is part of both the respiratory and the digestive systems. Air passes from the nasal cavity through the pharynx to the larynx (as well as in the opposite direction). Food passes from the mouth through the pharynx to the esophagus.

Larynx

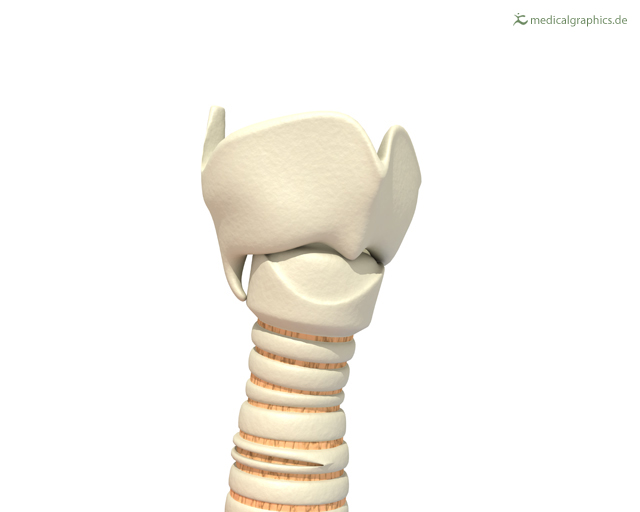

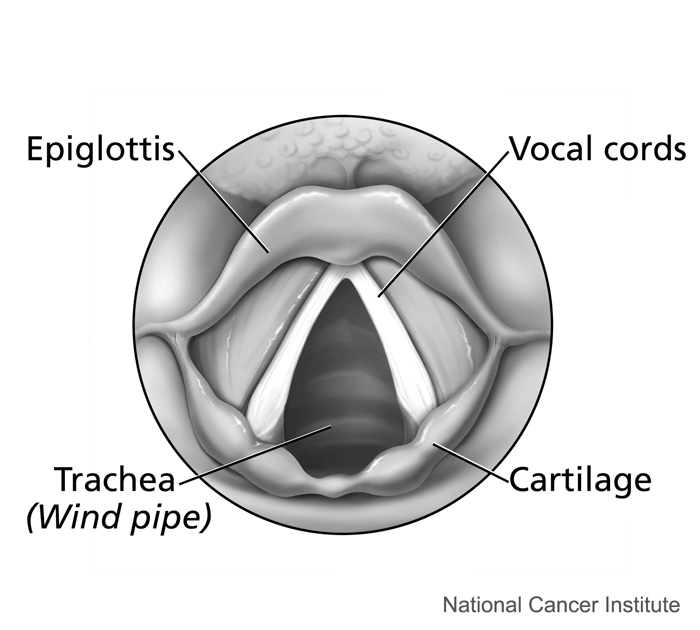

The larynx connects the pharynx and trachea, and helps to conduct air through the respiratory tract. The larynx is also called the voice box, because it contains the vocal cords, which vibrate when air flows over them, thereby producing sound. You can see the vocal cords in the larynx in Figures 12.3 and 12.4. Certain muscles in the larynx move the vocal cords apart to allow breathing. Other muscles in the larynx move the vocal cords together to allow the production of vocal sounds. The latter muscles also control the pitch of sounds and help control their volume.

A very important function of the larynx is protecting the trachea from aspirated food. When swallowing occurs, the backward motion of the tongue forces a flap called the epiglottis to close over the entrance to the larynx. (You can see the epiglottis in both Figure 12.3 and 12.4.) This prevents swallowed material from entering the larynx and moving deeper into the respiratory tract. If swallowed material does start to enter the larynx, it irritates the larynx and stimulates a strong cough reflex. This generally expels the material out of the larynx, and into the throat.

Figure 12.3 The larynx as viewed from externally. Figure 12.4 The larynx as viewed from the top.

Larynx Model – Respiratory System, Dr. Lotz, 2018.

LOWER RESPIRATORY TRACT

The trachea and other passages of the lower respiratory tract conduct air between the upper respiratory tract and the lungs. These passages form an inverted tree-like shape (Figure 12.5), with repeated branching as they move deeper into the lungs. All told, there are an astonishing 2,414 kilometers (1,500 miles) of airways conducting air through the human respiratory tract! It is only in the lungs, however, that gas exchange occurs between the air and the bloodstream.

Trachea

The trachea, or windpipe, is the widest passageway in the respiratory tract. It is about 2.5 cm wide and 10-15 cm long (approximately 1 inch wide and 4–6 inches long). It is formed by rings of cartilage, which make it relatively strong and resilient. The trachea connects the larynx to the lungs for the passage of air through the respiratory tract. The trachea branches at the bottom to form two bronchial tubes.

Bronchi and Bronchioles

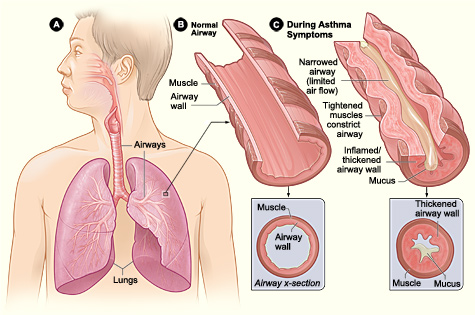

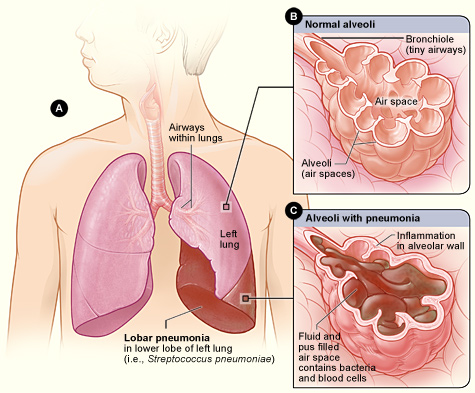

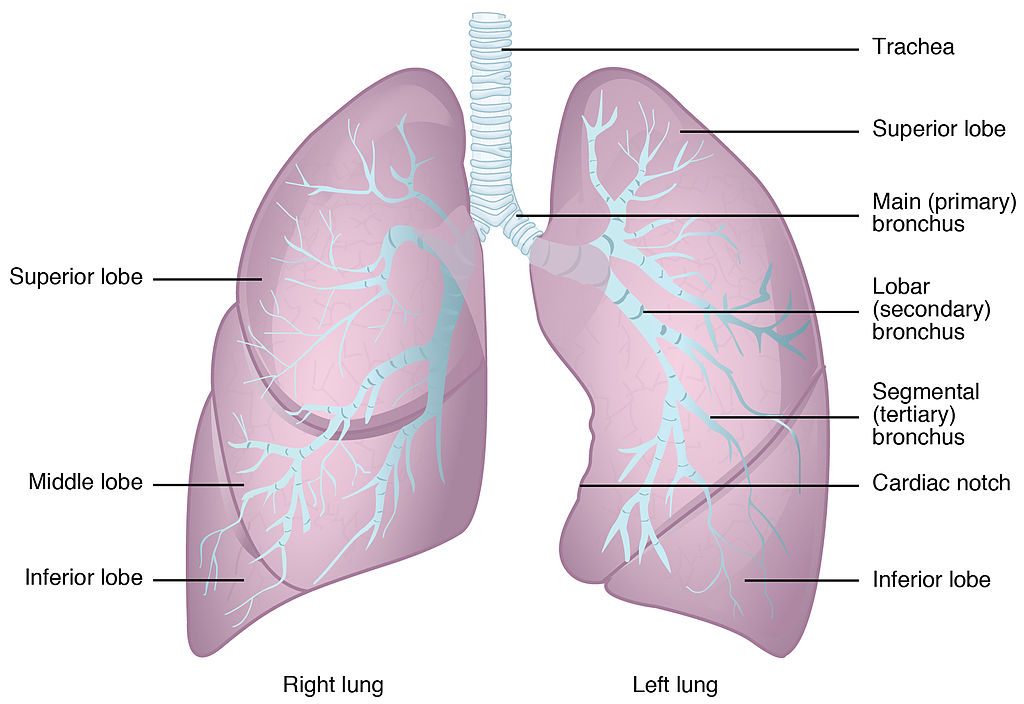

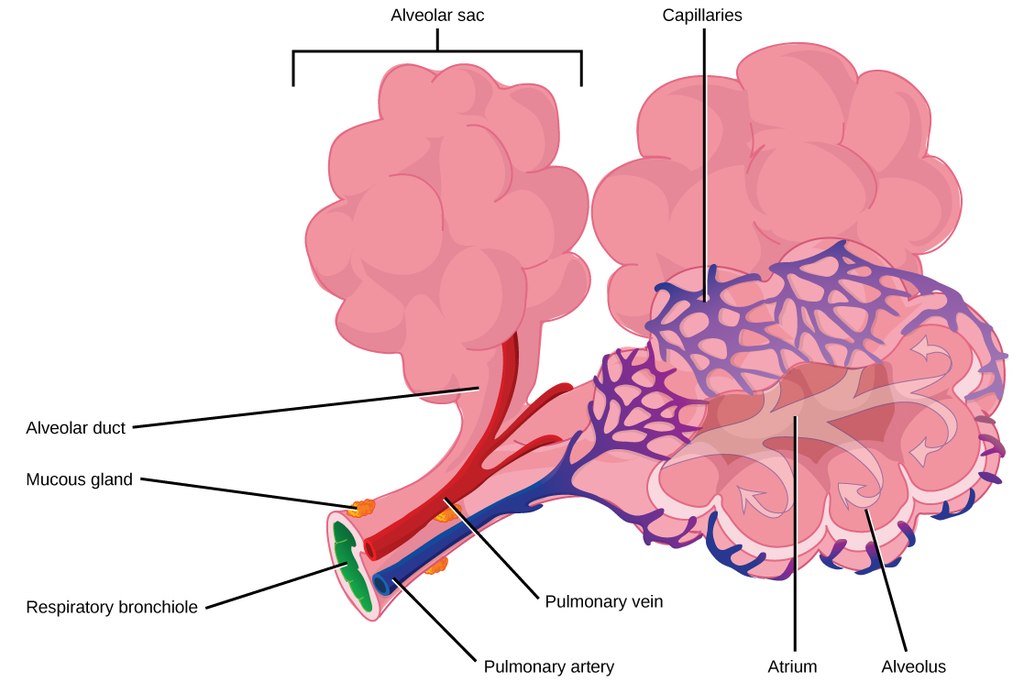

There are two main bronchial tubes, or bronchi (singular, bronchus), called the right and left bronchi. The bronchi carry air between the trachea and lungs. Each bronchus branches into smaller, secondary bronchi; and secondary bronchi branch into still smaller tertiary bronchi. The smallest bronchi branch into very small tubules called bronchioles. The tiniest bronchioles end in alveolar ducts, which terminate in clusters of minuscule air sacs, called alveoli(singular, alveolus), in the lungs.

Lungs

The lungs are the largest organs of the respiratory tract. They are suspended within the pleural cavity of the thorax. The lungs are surrounded by two thin membranes called pleura, which secrete fluid that allows the lungs to move freely within the pleural cavity. This is necessary so the lungs can expand and contract during breathing. In Figure 13.2.6, you can see that each of the two lungs is divided into sections. These are called lobes, and they are separated from each other by connective tissues. The right lung is larger and contains three lobes. The left lung is smaller and contains only two lobes. The smaller left lung allows room for the heart, which is just left of the center of the chest.

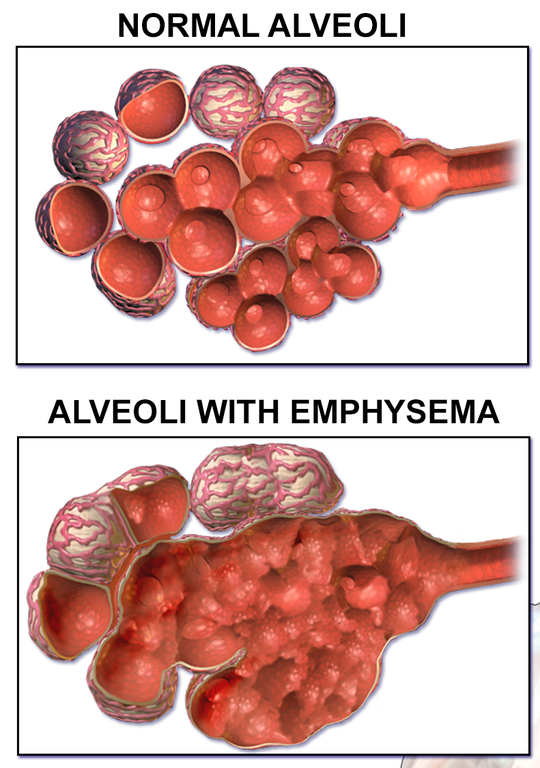

As mentioned previously, the bronchi terminate in bronchioles which feed air into alveoli, tiny sacs of simple squamous epithelial tissue which make up the bulk of the lung. The cross-section of lung tissue in the diagram below (Figure 12.7) shows the alveoli, in which gas exchange takes place with the capillary network that surrounds them.

|

|

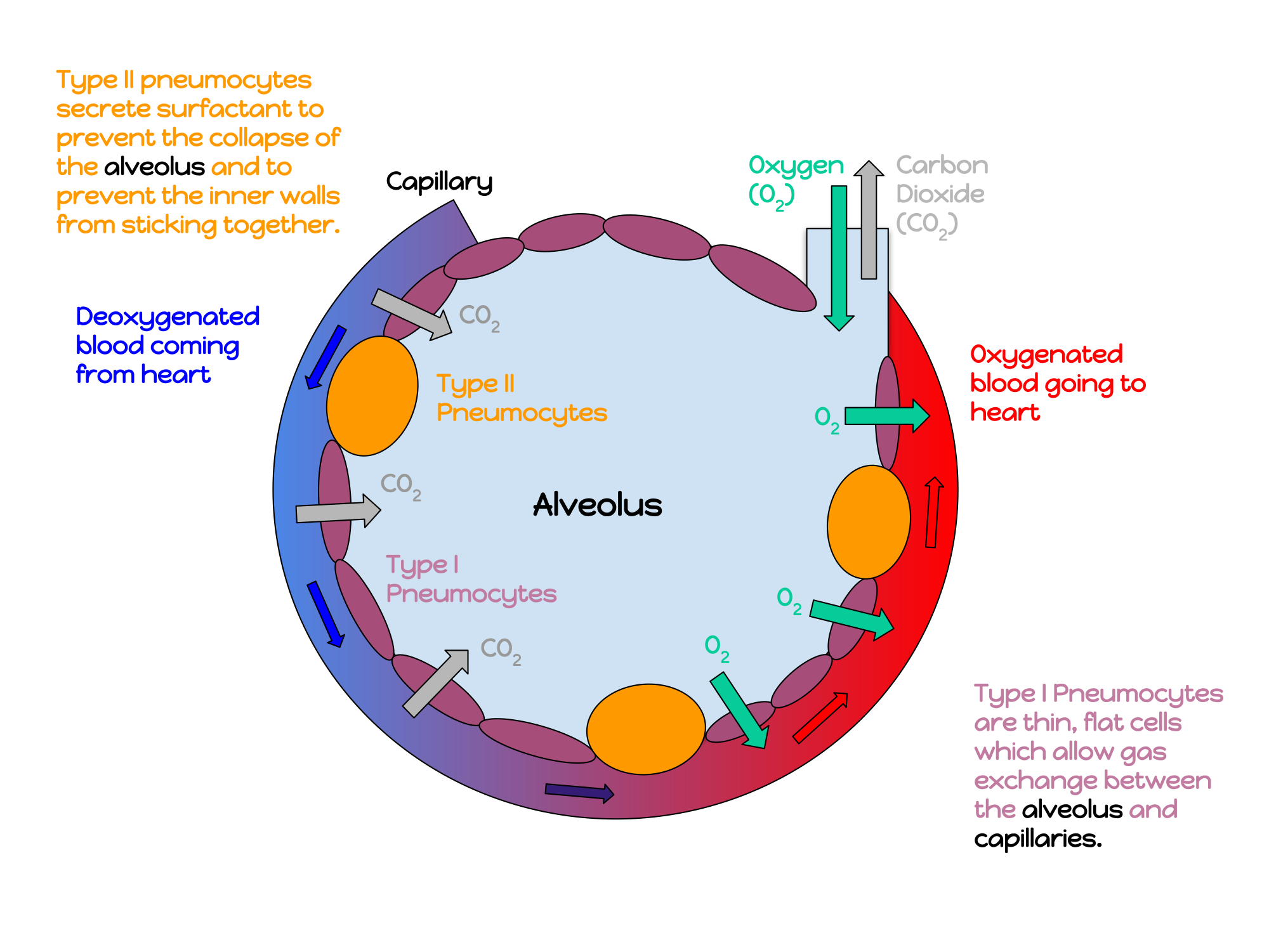

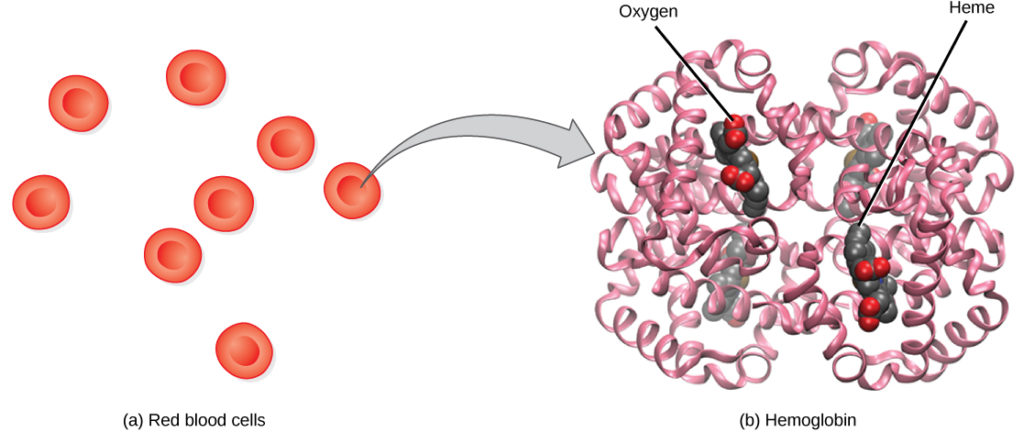

Lung tissue consists mainly of alveoli (see Figures 12.7 and 12.8). These tiny air sacs are the functional units of the lungs where gas exchange takes place. The two lungs may contain as many as 700 million alveoli, providing a huge total surface area for gas exchange to take place. In fact, alveoli in the two lungs provide as much surface area as half a tennis court! Each time you breathe in, the alveoli fill with air, making the lungs expand. Oxygen in the air inside the alveoli is absorbed by the blood via diffusion in the mesh-like network of tiny capillaries that surrounds each alveolus. The blood in these capillaries also releases carbon dioxide (also by diffusion) into the air inside the alveoli. Each time you breathe out, air leaves the alveoli and rushes into the outside atmosphere, carrying waste gases with it.

The lungs receive blood from two major sources. They receive deoxygenated blood from the right side of the heart. This blood absorbs oxygen in the lungs and carries it back to the left side heart to be pumped to cells throughout the body. The lungs also receive oxygenated blood from the heart that provides oxygen to the cells of the lungs for cellular respiration.

PROTECTING THE RESPIRATORY SYSTEM

You may be able to survive for weeks without food and for days without water, but you can survive without oxygen for only a matter of minutes — except under exceptional circumstances — so protecting the respiratory system is vital. Ensuring that a patient has an open airway is the first step in treating many medical emergencies. Fortunately, the respiratory system is well protected by the ribcage of the skeletal system. The extensive surface area of the respiratory system, however, is directly exposed to the outside world and all its potential dangers in inhaled air. It should come as no surprise that the respiratory system has a variety of ways to protect itself from harmful substances, such as dust and pathogens in the air.

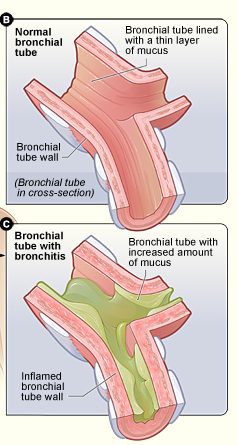

The main way the respiratory system protects itself is called the mucociliary escalator. From the nose through the bronchi, the respiratory tract is covered in epithelium that contains mucus-secreting goblet cells. The mucus traps particles and pathogens in the incoming air. The epithelium of the respiratory tract is also covered with tiny cell projections called cilia (singular, cilium), as shown in the animation. The cilia constantly move in a sweeping motion upward toward the throat, moving the mucus and trapped particles and pathogens away from the lungs and toward the outside of the body. The upward sweeping motion of cilia lining the respiratory tract helps keep it free from dust, pathogens, and other harmful substances.

Mucociliary clearance, I-Hsun Wu, 2015.

Sneezing is a similar involuntary response that occurs when nerves lining the nasal passage are irritated. It results in forceful expulsion of air from the mouth, which sprays millions of tiny droplets of mucus and other debris out of the mouth and into the air, as shown in Figure 12.9. This explains why it is so important to sneeze into a tissue (rather than the air) if we are to prevent the transmission of respiratory pathogens.

How the Respiratory System Works with Other Organ Systems

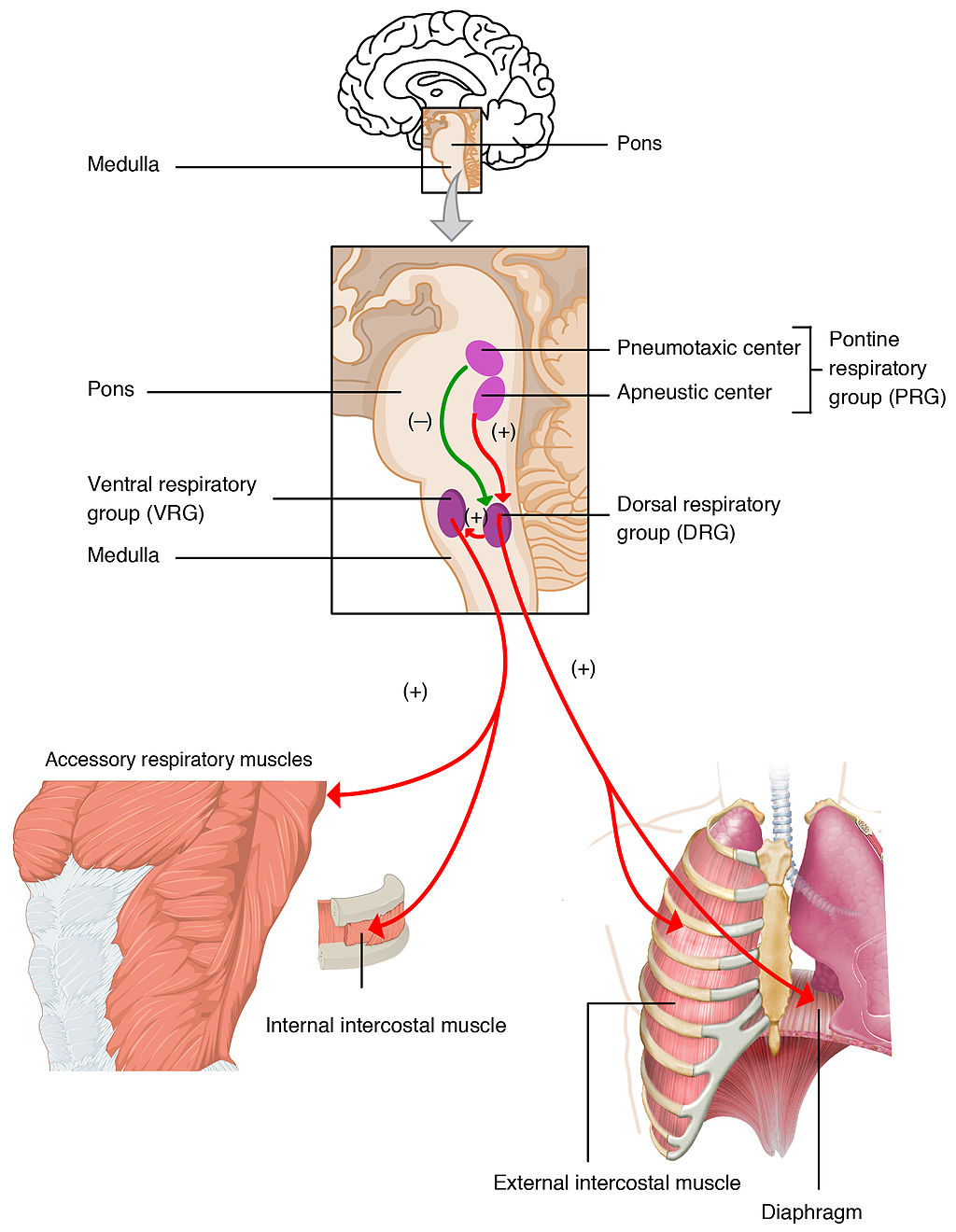

The amount of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the blood must be maintained within a limited range for survival of the organism. Cells cannot survive for long without oxygen, and if there is too much carbon dioxide in the blood, the blood becomes dangerously acidic (pH is too low). Conversely, if there is too little carbon dioxide in the blood, the blood becomes too basic (pH is too high). The respiratory system works hand-in-hand with the nervous and cardiovascular systems to maintain homeostasis in blood gases and pH.

It is the level of carbon dioxide — rather than the level of oxygen — that is most closely monitored to maintain blood gas and pH homeostasis. The level of carbon dioxide in the blood is detected by cells in the brain, which speed up or slow down the rate of breathing through the autonomic nervous system as needed to bring the carbon dioxide level within the normal range. Faster breathing lowers the carbon dioxide level (and raises the oxygen level and pH), while slower breathing has the opposite effects. In this way, the levels of carbon dioxide, oxygen, and pH are maintained within normal limits.

The respiratory system also works closely with the cardiovascular system to maintain homeostasis. The respiratory system exchanges gases with the outside air, but it needs the cardiovascular system to carry them to and from body cells. Oxygen is absorbed by the blood in the lungs and then transported through a vast network of blood vessels to cells throughout the body, where it is needed for aerobic cellular respiration. The same system absorbs carbon dioxide from cells and carries it to the respiratory system for removal from the body.

FEATURE: MY HUMAN BODY

Choking due to a foreign object becoming lodged in the airway results in nearly 5 thousand deaths in Canada each year. In addition, choking accounts for almost 40% of unintentional injuries in infants under the age of one. For the sake of your own human body, as well as those of loved ones, you should be aware of choking risks, signs, and treatments.

Choking is the mechanical obstruction of the flow of air from the atmosphere into the lungs. It prevents breathing, and may be partial or complete. Partial choking allows some — though inadequate — air flow into the lungs. Prolonged or complete choking results in asphyxia, or suffocation, which is potentially fatal.

Obstruction of the airway typically occurs in the pharynx or trachea. Young children are more prone to choking than are older people, in part because they often put small objects in their mouth and do not understand the risk of choking that they pose. Young children may choke on small toys or parts of toys, or on household objects, in addition to food. Foods that are round (hotdogs, carrots, grapes) or can adapt their shape to that of the pharynx (bananas, marshmallows), are especially dangerous, and may cause choking in adults, as well as children.

How can you tell if a loved one is choking? The person cannot speak or cry out, or has great difficulty doing so. Breathing, if possible, is labored, producing gasping or wheezing. The person may desperately clutch at his or her throat or mouth. If breathing is not soon restored, the person’s face will start to turn blue from lack of oxygen. This will be followed by unconsciousness, brain damage, and possibly death if oxygen deprivation continues beyond a few minutes.

If an infant is choking, turning the baby upside down and slapping him on the back may dislodge the obstructing object. To help an older person who is choking, first encourage the person to cough. Give them a few hard back slaps to help force the lodged object out of the airway. If these steps fail, perform the Heimlich maneuver on the person. See the series of videos below, from ProCPR, which demonstrate several ways to help someone who is choking based on age.

Figure 12.18 Transport of carbon dioxide

Figure 12.18 Transport of carbon dioxide