Chapter 4 – Introduction to Tort Law

4.2 Types of Torts

There are three kinds of torts: intentional torts, negligent torts, and strict liability torts. Intentional torts arise from intentional acts, whereas unintentional torts often result from carelessness. Both intentional torts and negligent torts imply some fault on the part of the defendant. In strict liability torts, by contrast, there may be no fault at all, but tort law will sometimes require a defendant to make up for the victim’s losses even where the defendant was not careless and did not intend to do harm.

Dimensions of Tort Liability

There is a clear moral basis for recovery through the legal system where the defendant has been careless (negligent) or has intentionally caused harm. Using the concepts that we are free and autonomous beings with basic rights, we can see that when others interfere with either our freedom or our autonomy, we will usually react negatively. As the old saying goes, “Your right to swing your arm ends at the tip of my nose.” The law takes this even one step further: under intentional tort law, if you frighten someone by swinging your arms toward the tip of her nose, you may have committed the tort of assault, even if there is no actual touching (battery).

Under a capitalistic market system, rational economic rules also call for no negative externalities. That is, actions of individuals, either alone or in concert with others, should not negatively impact third parties. The law will try to compensate third parties who are harmed by your actions, even though it knows that a money judgment cannot actually mend a badly injured victim.

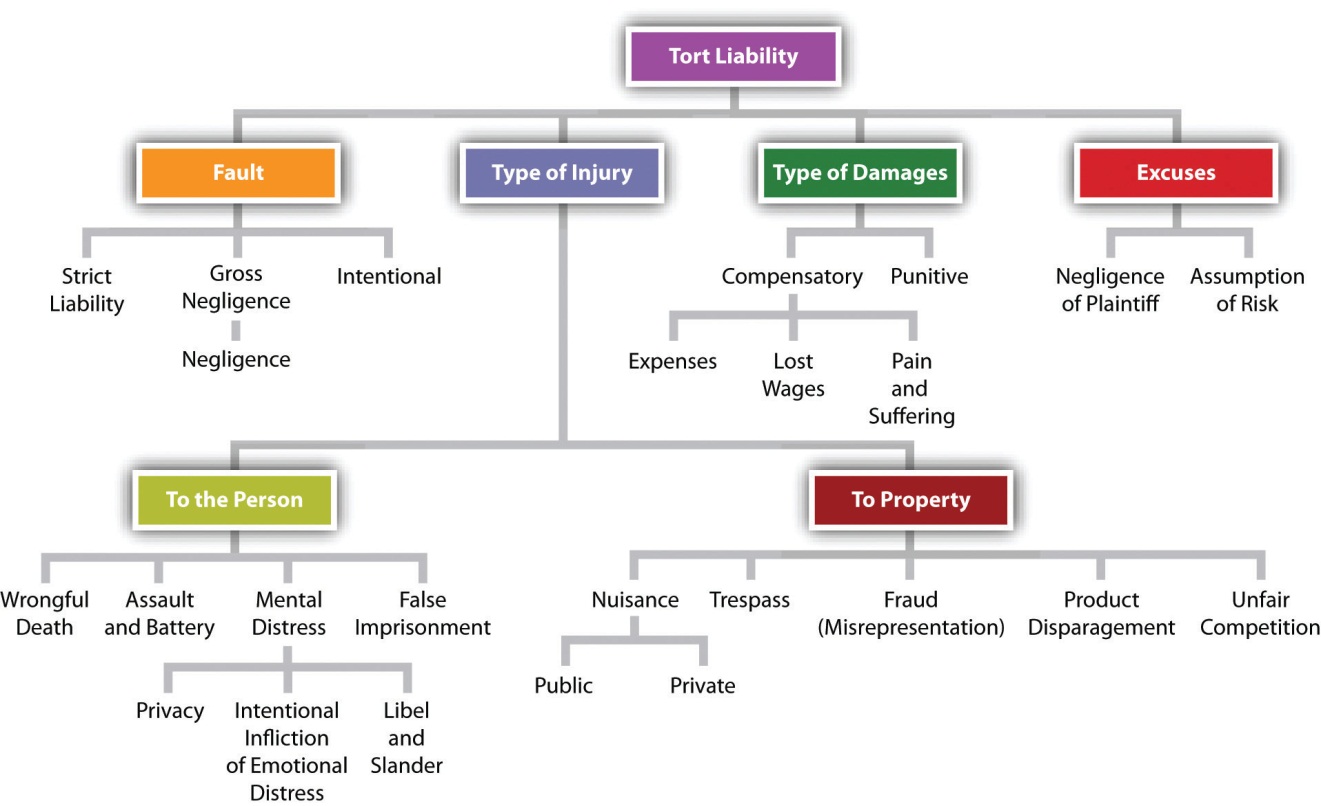

Figure 4.1 Dimensions of Tort Liability

Fault

Tort principles can be viewed along different dimensions. One is the fault dimension which requires a wrongful act by a defendant for the plaintiff to recover damages. The intent behind that act, however, need not be a specific intent. In other words, an innocent or relatively innocent action may still provide the basis for liability. Nevertheless, tort law—except for strict liability—relies on standards of fault, or blameworthiness.

The most obvious standard is willful conduct. If the defendant intentionally injures another, there is little argument about fault and tort liability. Thus, all crimes resulting in injury to a person or property (murder, assault, arson, etc.) are also torts, and the plaintiff may bring a civil lawsuit to recover damages for injuries to his person, family, or property.

Most tort suits do not rely on intentional fault. Most tort suits arise from negligent conduct that in the circumstances is careless or poses unreasonable risks of causing damage. Most automobile accident and medical malpractice suits are examples of negligence suits.

The fault dimension is a continuum. At one end of the continuum is the deliberate desire to do injury. The middle ground is occupied by careless conduct or negligence, and then at the other end of the continuum – no fault – is conduct that most would consider entirely blameless. In other words, the defendant may have observed all possible precautions and yet still be held liable. This is called strict liability. Here are examples illustrating the three different types of torts discussed in this section.

Sandy is at a shooting range practicing her marksmanship. Sandy gets into an argument with James. While yelling at James, Sandy points the gun toward him, and the gun discharges unexpectedly and a bullet strikes and injures James.

Sandy is at a shooting range practicing her marksmanship and showing James how to use her gun. James has not handled a gun before, and Sandy gives James the gun without making sure that the gun isn’t loaded with live bullets. It turns out the gun is loaded, it discharges unexpectedly and a bullet strikes and injures James.

Sandy is at a shooting range practicing her marksmanship. The gun she uses is made by a manufacturer with a reputation for producing high-quality firearms. However, due to an unforeseen manufacturing defect in one batch of guns, a small number of them occasionally discharge unexpectedly. Sandy has unknowingly purchased one of those guns. Sandy is using reasonable safety precautions while using the gun, but without any warning the gun discharges unexpectedly injuring James.

Nature of Injury

Tort liability varies by the type of injury caused. The most obvious type of injury is physical harm to the person (assault, battery, infliction of emotional distress, negligent exposure to toxic pollutants, wrongful death). Mental suffering can be redressed if it is a result of physical injury (e.g., shock and depression following an automobile accident). A few states now permit recovery for mental distress without a physical injury (a mother’s shock at seeing her son injured by a car while both were crossing the street). Other protected interests include a person’s reputation (injured by defamatory statements or writings), a person’s privacy (injured by those who divulge secrets of his personal life), and a person’s economic interests (misrepresentation to secure an economic advantage, certain forms of unfair competition).

Other torts don’t result in harm to a person, but instead result in harm to their property (trespass, nuisance, interference with contract).

Damages

Since the purpose of tort law is to compensate the victim for harm actually done, damages are usually measured by the extent of the injury. Expressed in money terms, these include replacement of property destroyed, compensation for lost wages, reimbursement for medical expenses, and dollars that are supposed to approximate the pain that is suffered. Damages for these injuries are called compensatory damages.

In certain instances, the courts will permit an award of punitive damages. As the word punitive implies, the purpose is to punish the defendant’s actions. Because a punitive award (sometimes called exemplary damages) is at odds with the general purpose of tort law, it is allowable only in aggravated situations. The law in most states permits recovery of punitive damages only when the defendant has deliberately committed a wrong with malicious intent or has otherwise done something outrageous.

Punitive damages are rarely allowed in negligence cases for that reason. But if someone sets out intentionally and maliciously to hurt another person, punitive damages may well be appropriate. Punitive damages are intended not only to punish the wrongdoer, by exacting an additional and sometimes heavy payment (the exact amount is left to the discretion of jury and judge), but also to deter others from similar conduct. The punitive damage award has been subject to heavy criticism in recent years in cases in which it has been awarded against manufacturers. One fear is that huge damage awards on behalf of a multitude of victims could swiftly bankrupt the defendant. Unlike compensatory damages, punitive damages are taxable.

Excuses

The law does not condemn every act that ultimately results in injury. Excuses are recognized under certain circumstances when the defendant’s actions, although they might have caused harm, are considered justified or excusable due to specific reasons.

One common rule of exculpation is assumption of risk. A baseball fan who sits along the third base line close to the infield assumes the risk that a line drive foul ball may fly toward him and strike him. He will not be permitted to complain in court that the batter should have been more careful or that management should have either warned him or put up a protective barrier.

Another excuse is negligence of the plaintiff. If two drivers are careless and hit each other on the highway, some states will refuse to permit either to recover from the other. Still another excuse is consent: two boxers in the ring consent to being struck with fists (but not to being bitten on the ear).

Breach of Duty of Care

Breach of duty of care occurs when the defendant fails to meet the standard of care that a reasonably prudent person would have exercised in similar circumstances. A plaintiff must demonstrate that the defendant’s actions (or inactions) fell below the expected standard of care, indicating negligence. Essentially, the defendant’s behavior did not meet the level of care that a reasonable person would have taken.

Establishing a breach of the duty of due care where the defendant has violated a statute or municipal ordinance is eased considerably with the doctrine of negligence per se, a doctrine common to all U.S. state courts. If a legislative body sets a minimum standard of care for particular kinds of acts to protect a certain set of people from harm and a violation of that standard causes harm to someone in that set, the defendant is negligent per se. For example, If Harvey is driving sixty-five miles per hour in a fifty-five-mile-per-hour zone when he crashes into Haley’s car and the police accident report establishes that or he otherwise admits to going ten miles per hour over the speed limit, Haley does not have to prove that Harvey has breached a duty of due care. She will only have to prove that the speeding was an actual and proximate cause of the collision and will also have to prove the extent of the resulting damages to her.

Causation: Actual Cause and Proximate Cause

Causation involves establishing a direct link between the defendant’s breach of duty and the harm suffered by the plaintiff. In tort theory, there are two kinds of causes that a plaintiff must prove: actual cause and proximate cause. Actual cause (causation in fact) can be found if the connection between the defendant’s act and the plaintiff’s injuries passes the “but for” test: if an injury would not have occurred “but for” the defendant’s conduct, then the defendant is the cause of the injury. Still, this is not enough causation to create liability. The injuries to the plaintiff must also be foreseeable, or not “too remote,” for the defendant’s act to create liability. This is proximate cause: a cause that is not too remote or unforeseeable. For proximate cause, foreseeability is key. The harm suffered by the plaintiff must have been a foreseeable consequence of the defendant’s breach of duty.

a deliberate act that causes harm to another, and for which the injured person may sue the wrongdoer for damages

a tort claim that arises when a person or entity is careless and that carelessness injures or harms someone

a tort in which liability is imposed without regard to fault

responsibility for wrongdoing or failure

physical or mental damage

(1) the threat of immediate harm or offense of contact or (2) any act that would arouse reasonable apprehension of imminent harm

unauthorized and harmful or offensive physical contact with another person that causes injury

the state of being legally responsible for something

1) the money awarded to one party because of an injury or loss caused by another party; and 2) the harm an injured party suffers because of another party's wrongful conduct

failure to use reasonable care, resulting in injury or property damage to another

a wrongful act that causes injury

a legal claim that allows individuals to seek compensation for severe emotional distress or mental anguish caused by the intentional and outrageous conduct of another party

intentionally going on land that belongs to someone else or putting something on someone else’s property and refusing to remove it

the unreasonable interference with another person's use and enjoyment of their property

a third party intentionally takes actions to disrupt or interfere with an existing contractual relationship between two parties

damages awarded in a lawsuit as a punishment and example to others for malicious, evil or particularly fraudulent acts

damages awarded over and above special and general damages to punish a losing party's willful or malicious misconduct; sometimes called punitive damages

(1) a legal defense that a defendant can use in a negligence lawsuit if it can be shown that plaintiff voluntarily and knowingly accepted the risks associated with a certain activity or situation, and therefore, the defendant should not be held liable for any resulting injuries or harm; (2) the act of contracting to take over a risk

a failure or violation of a legal obligation -- for example, a failure to perform a contract (breaching its terms)

an obligation to use due care toward others in order to protect them from unnecessary risk of harm

negligence due to a violation of law designed to protect the public, such as a speed limit or building code

establishing a direct link between the defendant's breach of duty and the harm suffered by the plaintiff

a legal relationship, created by law or contract, in which a person or business owes something to another

cause in fact

a cause that is not too remote or unforeseeable