Chapter 11 – Written Contracts

11.1 General Perspectives on the Statute of Frauds

Introduction to the Statute of Frauds

In prior chapters, we have focused on the question of whether the parties created a valid contract and have examined the requirements of agreement through offer and acceptance, consideration, capacity and legality. Assuming that these requirements have been met, we now turn to the form and meaning of the contract itself. This Chapter answers two important questions:

- Does the contract have to be in a written form?

- If the contract is in written form and there is a dispute, how do we know what the contract means?

Generally, a contract need not be in writing to be enforceable. However, over time and due to concerns about fraudulent contracting, several statutes were enacted that have the impact of requiring certain contracts to be written in order to be enforceable.

Historical Perspective

Historically, an oral agreement to pay a high-fashion model $2 million to pose for photographs is as binding as if the language of the deal were printed on parchment and signed in the presence of twenty witnesses. For three centuries, however, a large exception grew up around what came to be known as the Statute of Frauds. The first Statute of Frauds was enacted in England in 1677 under the formal name “An Act for the Prevention of Frauds and Perjuries.” The English statute’s two sections dealing with contracts read as follows:

[Sect. 4]…no action shall be brought

- whereby to charge any executor or administrator upon any special promise, to answer damages out of his own estate;

- or whereby to charge the defendant upon any special promise to answer for the debt, default or miscarriages of another person;

- or to charge any person upon any agreement made upon consideration of marriage;

- or upon any contract or sale of lands, tenements or hereditaments, or any interest in or concerning them;

- or upon any agreement that is not to be performed within the space of one year from the making thereof;

unless the agreement upon which such action shall be brought, or some memorandum or note thereof, shall be in writing, and signed by the party to be charged therewith, or some other person thereunto by him lawfully authorized.

[Sect. 17]…no contract for the sale of any goods, wares and merchandizes, for the price of ten pounds sterling or upwards, shall be allowed to be good, except the buyer shall accept part of the goods so sold, and actually receive the same, or give something in earnest to bind the bargain or in part of payment, or that some note or memorandum in writing of the said bargain be made and signed by the parties to be charged by such contract, or their agents thereunto lawfully authorized.

As may be evident from the title of the act and the language used within it, the general purpose of the law is to provide evidence, in areas of some complexity and importance, that a contract was actually made. Succinctly, the purpose is to prevent fraud in certain types of contracts by requiring a written contract.

Notice, of course, that this is a statute; it is a legislative intrusion into the common law of contracts. In addition, the name given to this class of statutes can be somewhat confusing. These statutes do not deal with fraud as you might normally think of it. They are, instead, attempts to avoid fraud in contracting. The Statute of Frauds, therefore, tells us when a contract is required to be evidenced by a writing and signed by the party to be bound to that contract.

The Statute of Frauds has been enacted in form similar to the seventeenth-century act in every state except Maryland and New Mexico – where judicial decisions have given it legal effect – and Louisiana. With minor exceptions in Minnesota, Wisconsin, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania, the laws all embrace the same categories of contracts that are required to be in writing. Early in the twentieth century, Section 17 was replaced by a section of the Uniform Sales Act, and this in turn has now been replaced by provisions in the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC).

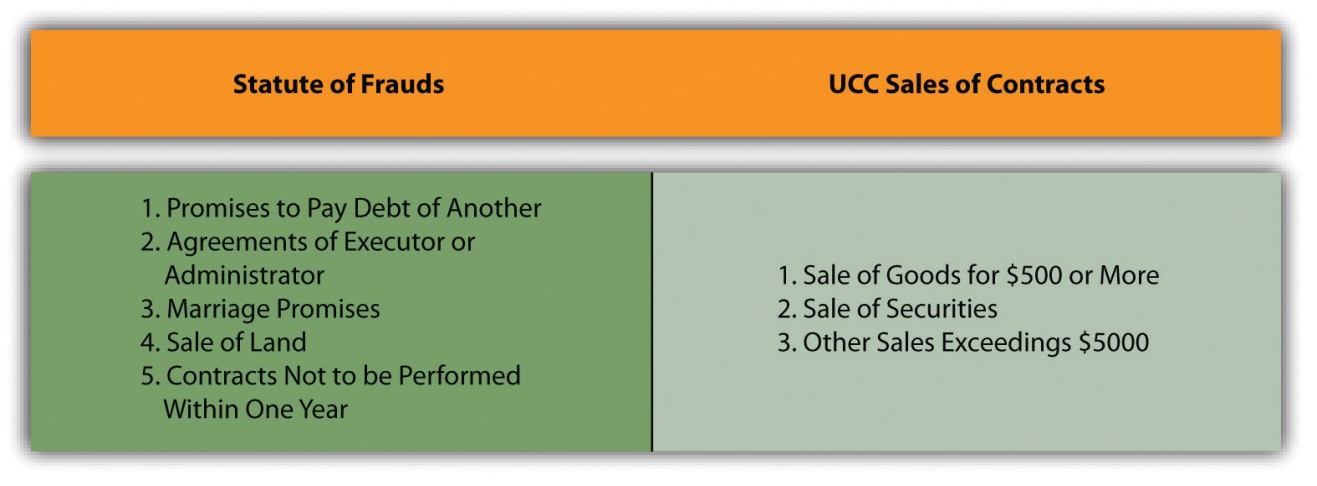

Figure 11.1 Contracts Required to Be in Writing

However ancient, the Statute of Frauds is alive and well in the United States. Today it is used as a technical defense in many contract actions, often with unfair results: it can be used by a person to wriggle out of an otherwise perfectly fine oral contract (it is said then to be used “as a sword instead of a shield”). Consequently, courts interpret the law strictly and over the years have enunciated a host of exceptions—making what appears to be a simple law quite complex. Indeed, after more than half a century of serious scholarly criticism, the British Parliament repealed most of the statute in 1954. Even in New Jersey, in 1995 there was some rolling back of our home state requirements for the Statutes of Frauds. Yet, because business transactions regularly span across state lines, it is important to understand all of the Statutes of Frauds that are in place in the United States today.

Check your Understanding

a legally binding and enforceable agreement that meets all the essential elements required by contract law

a specific proposal to enter into an agreement with another; an offer is essential to the formation of an enforceable contract

agreeing verbally or in writing to the terms of a contract, which is one of the requirements to show there was a contract

a benefit that is of value to both parties, which must be bargained for between the parties and is the essential reason for a party entering into a contract

legal ability of an individual or entity to enter into a binding contract and be held legally responsible for their actions and obligations under that contract

strict adherence to law; the quality of being legal

a law in every state that requires certain types of documents to be in writing and signed by the party to be charged (usually, the defendant in a lawsuit)

a set of statutes governing the conduct of business, sales, warranties, negotiable instruments, loans secured by personal property and other commercial matters