Chapter 6 – The Agreement

6.4 The Acceptance

To result in a legally binding contract, an offer must be accepted by the offeree. Just as the law helps define and shape an offer and its duration, so too does the law govern the nature and manner of acceptance. The Restatement defines acceptance of an offer as “a manifestation of assent to the terms thereof made by the offeree in a manner invited or required by the offer.” In showing that there is an assent to an offer, the acceptance will reflect back the intention and terms of the offer, either by the making of a mutual promise or by performance or partial performance of a requested action. If there is doubt about whether the offer requests a return promise or a return act, the Restatement, Section 32, provides that the offeree may accept with either a promise or performance. The UCC also adopts this view; under Section 2-206(1)(a), “an offer to make a contract shall be construed as inviting acceptance in any manner and by any medium reasonable in the circumstances” unless the offer unambiguously requires a certain mode of acceptance.

The person to whom a promise is directed is ordinarily the person whom the offeror contemplates will make a return promise or perform the act requested. As such, in the typical case, the offeror directs the offer to the offeree, and that party is then in the position to accept the offer, or decide not to accept. Under the common law, whoever is invited to furnish consideration to the offeror is the offeree, and only an offeree may accept an offer. Yet in some situations, a promise can be made to one person who is not expected to do anything in return. In this case, consideration necessary to weld the offer and acceptance into a legal contract can be given by a third party. A common example is sale to a minor. George promises to sell his automobile to Bartley, age seventeen, if Bartley’s father will promise to pay $3,500 to George. Bartley is the promisee (the person to whom the promise is made) but not the offeree; Bartley cannot legally accept George’s offer. Only Bartley’s father, who is called on to pay for the car, can accept, by making the promise requested. And notice what might seem obvious: a promise to perform as requested in the offer is itself a binding acceptance.

When Is Acceptance Effective?

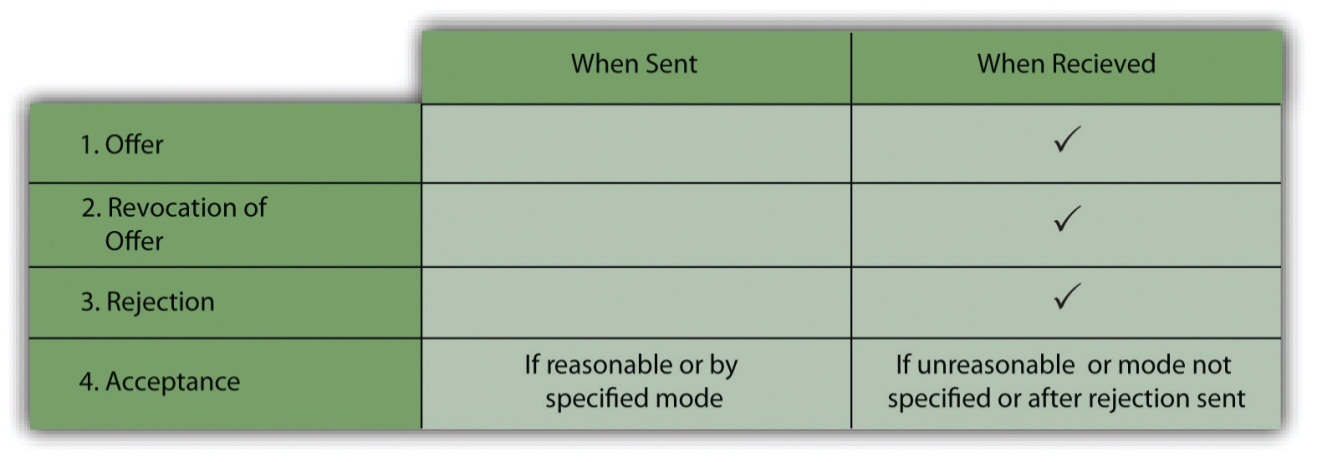

As noted previously, an offer, a revocation of the offer, and a rejection of the offer are not effective until received. However, the same rules will not apply when evaluating whether an acceptance is effective. When communications are instantaneous, such as in a face-to-face negotiation, the precise moment of acceptance is not in question. So, too, would be negotiations taking place over telephone or other means of communicating in real time such as Facetime, or Zoom. But disagreements can arise in contracts that are negotiated via means that are not in real time, such as via email.

Stipulations as to Acceptance

One common situation arises when the offeror stipulates the mode of acceptance (e.g., return mail, fax, or carrier pigeon). If the offeree uses the stipulated mode, then the acceptance is deemed effective when it is sent. Even though the offeror has no knowledge of the acceptance at that moment, the contract has been formed. Moreover, according to the Restatement, if the offeror says that the offer can be accepted only by the specified mode, that mode must be used or any acceptance by an alternative mode is invalid.

If the offeror specifies no particular mode, then acceptance is effective when transmitted, as long as the offeree uses a reasonable method of acceptance. It is implied that the offeree can use the same means used by the offeror or a means of communication customary to the industry.

The “Mailbox Rule”

The use of the postal service is customary, so acceptances are considered effective when mailed, regardless of the method used to transmit the offer. In other words, under the mailbox rule, an acceptance is generally effective and binding on the parties at the moment it is sent or deposited in a mailbox.

The mailbox rule may seem to create particular difficulties for people in business. As the acceptance is effective when sent, the offeror is unaware of the acceptance. The offeror will eventually become aware of the acceptance when it is ultimately received, but that will be after the agreement is formed. It is even possible that the letter notifying the offeror of an acceptance is lost and never arrives. Despite this concern, the law recognizes that in contracts negotiated through correspondence, this burden will always fall to one of the parties. So, if the rule were that the acceptance is not effective until received by the offeror, then the offeree would not be able to rely on the existence of an agreement. As between the two, it seems fairer to place the burden on the offeror, since he or she alone has the power to fix the moment of effectiveness. All the offeror need do is specify in the offer that acceptance is not effective until received.

The mailbox rule eliminates an additional burden of acknowledging the acceptance in order for the agreement to become effective. But note that the offeree must use a mode of acceptance that is reasonable—acceptance is deemed effective only when received.

Acceptance “Outruns” Rejection

When the offeree sends a rejection first and then later transmits a superseding acceptance, the “effective when received” rule also applies. Suppose a seller offers a buyer two cords of firewood and says the offer will remain open for a week. On the third day, the buyer writes the seller, rejecting the offer. The following evening, the buyer rethinks his firewood needs, and on the morning of the fifth day, he sends an e-mail accepting the seller’s terms. The previously mailed letter arrives the following day. Since the letter rejecting the offer had not yet been received, the offer had not been rejected. For there to be a valid contract, the e-mailed acceptance must arrive before the mailed rejection. If the e-mail were hung up in cyberspace, through no fault of the buyer, so that the letter arrived first, the seller would be correct in assuming the offer was terminated—even if the e-mail arrived a minute later. In short, where “the acceptance outruns the rejection” the acceptance is effective.

Figure 9.1 – Summary of Rules for Timing of Offer and Acceptance

Electronic Communications

Electronic communications are increasingly common. Many contracts are negotiated by e-mail, accepted and “signed” electronically. Generally speaking, this does not change the rules. The Uniform Electronic Transactions Act (UETA) was promulgated (i.e., disseminated for states to adopt) in 1999. It is one of a number of uniform acts, like the Uniform Commercial Code. As of June 2010, forty-seven states and the U.S. Virgin Islands had adopted the statute. The introduction to the act provides that “the purpose of the UETA is to remove barriers to electronic commerce by validating and effectuating electronic records and signatures.” In general, the UETA provides the following:

- A record or signature may not be denied legal effect or enforceability solely because it is in electronic form

- A contract may not be denied legal effect or enforceability solely because an electronic record was used in its formation

- If a law requires a record to be in writing, an electronic record satisfies the law

- If a law requires a signature, an electronic signature satisfies the law

The UETA, though, doesn’t address all the problems with electronic contracting. Clicking on a computer screen may constitute a valid acceptance of a contractual offer, but only if the offer is clearly communicated. In Specht v. Netscape Communications Corp., customers who had downloaded a free online computer program complained that it effectively invaded their privacy by inserting into their machines “cookies”; they wanted to sue, but the defendant said they were bound to arbitration. They had clicked on the Download button, but hidden below it were the licensing terms, including the arbitration clause. The federal court of appeals held that there was no valid acceptance. The court said, “We agree with the district court that a reasonably prudent Internet user in circumstances such as these would not have known or learned of the existence of the license terms before responding to defendants’ invitation to download the free software, and that defendants therefore did not provide reasonable notice of the license terms. In consequence, the plaintiffs’ bare act of downloading the software did not unambiguously manifest assent to the arbitration provision contained in the license terms.”

If a faxed document is sent but for some reason not received or not noticed, the emerging law is that the mailbox rule does not apply. A court would examine the circumstances with care to determine the reason for the nonreceipt or for the offeror’s failure to notice its receipt. A person has to have fair notice that his or her offer has been accepted, and modern communication makes the old-fashioned mailbox rule—that acceptance is effective upon dispatch—problematic.

Silence is Not Acceptance

Ordinarily, for there to be a contract, the offeree must make some positive manifestation of assent to the offeror’s terms. The law does not impose on the offeree a duty to speak. Therefore, an offeror cannot usually word his offer in such a way that the offeree’s failure to respond can be construed as an acceptance.

Exceptions

The Restatement recognizes three situations in which silence can operate as an acceptance. The first occurs when the offeree takes a benefit from the offeror and avails himself of services proffered by the offeror, even though he could have rejected them and had reason to know that the offeror offered them expecting compensation. The second situation occurs when the offer states that the offeree may accept without responding and the offeree, remaining silent, intends to accept. The intention of the offeree is key. The third situation is that of previous dealings, in which only if the offeree intends not to accept is it reasonable to expect him to say so. To illustrate these three exceptions, suppose Emma subscribes to a cloud-based software service, and her subscription is up for renewal. If Emma continues to use the software and benefits from it after the renewal without objecting to the fee or canceling the renewal, she has accepted taking the benefit. If the original terms of use and agreement between the parties explicitly state, “Your subscription will be automatically renewed after one year unless you notify us within 30 days that you wish to cancel,” and Emma receives a notice about the renewal but doesn’t respond or cancel her subscription within the specified timeframe, this is acceptance as allowed in the offer. Finally, if Emma has been using this software for several years, and every year the software company sends her a renewal notice with similar terms, and she has never canceled her subscription in the past, the software company would base Emma’s acceptance on the history of their previous dealings.

Video on Acceptance

This video explains acceptance of unilateral and bilateral contracts.

Case 6.3

Hobbs v. Massasoit Whip Co., 33 N.E. 495 (Mass. 1893)

HOLMES, J.

This is an action for the price of eel skins sent by the plaintiff to the defendant, and kept by the defendant some months, until they were destroyed. It must be taken that the plaintiff received no notice that the defendant declined to accept the skins. The case comes before us on exceptions to an instruction to the jury that, whether there was any prior contract or not, if skins are sent to the defendant, and it sees fit, whether it has agreed to take them or not, to lie back, and to say nothing, having reason to suppose that the man who has sent them believes that it is taking them, since it says nothing about it, then, if it fails to notify, the jury would be warranted in finding for the plaintiff.

Standing alone, and unexplained, this proposition might seem to imply that one stranger may impose a duty upon another, and make him a purchaser, in spite of himself, by sending goods to him, unless he will take the trouble, and bear the expense, of notifying the sender that he will not buy. The case was argued for the defendant on that interpretation. But, in view of the evidence, we do not understand that to have been the meaning of the judge and we do not think that the jury can have understood that to have been his meaning. The plaintiff was not a stranger to the defendant, even if there was no contract between them. He had sent eel skins in the same way four or five times before, and they had been accepted and paid for. On the defendant’s testimony, it was fair to assume that if it had admitted the eel skins to be over 22 inches in length, and fit for its business, as the plaintiff testified and the jury found that they were, it would have accepted them; that this was understood by the plaintiff; and, indeed, that there was a standing offer to him for such skins.

In such a condition of things, the plaintiff was warranted in sending the defendant skins conforming to the requirements, and even if the offer was not such that the contract was made as soon as skins corresponding to its terms were sent, sending them did impose on the defendant a duty to act about them; and silence on its part, coupled with a retention of the skins for an unreasonable time, might be found by the jury to warrant the plaintiff in assuming that they were accepted, and thus to amount to an acceptance. [Citations] The proposition stands on the general principle that conduct which imports acceptance or assent is acceptance or assent, in the view of the law, whatever may have been the actual state of mind of the party—a principle sometimes lost sight of in the cases. [Citations]

Exceptions overruled.

Case questions

- What is an eel, and why would anybody make a whip out of its skin?

- Why did the court here deny the defendant’s assertion that it never accepted the plaintiff’s offer?

- If it reasonably seems that silence is acceptance, does it make any difference what the offeree really intended?

Activity 6B

You be the Judge

In the early days of the internet, an internet services provider called America Online (AOL) dominated the market. One of its sales tactics was to use pop-up ads for products where it would directly bill its customers for those products a customer agreed to purchase by clicking a purchase button. The problem was that many people who received products at their doorstep – like digital cameras, digital CDs, printer fax/machines, and even a “Gardening for Dummies” book – said they never agreed to purchase the products. Yet, they were charged and billed for their purchase. As you think about this situation, what are the pros and cons of silence as acceptance in relationship to this type of shopping experience. Should we have different rules of law to apply where one party has payment information from the other party, as AOL did for its customers, allowing for billing without an affirmative acceptance?

Check Your Understanding

a specific proposal to enter into an agreement with another; an offer is essential to the formation of an enforceable contract

agreeing verbally or in writing to the terms of a contract, which is one of the requirements to show there was a contract

cancellation of a contract by the parties to it

a rule by which an acceptance is effective and binding on the parties at the moment it is sent or deposited in a mailbox

an act published by the Uniform Law Commission in 1999 giving electronic signatures and records (including contracts) the same legal effect as traditional handwritten signatures and paper documents under the statute of frauds

one to whom an offer is made

one who makes an offer