Chapter 5 – Introduction to Contract Law

5.2 Sources of Contract Law

The most important sources of contract law are state case law and state statutes (though there are also many federal statutes governing how contracts are made by and with the federal government).

Case Law

Law made by judges is called case law. Because contract law was made up in the common-law courtroom by individual judges as they applied rules to resolve disputes before them, it grew over time to formidable proportions. Because of this, much of U.S. contract law is rooted in common law principles. Common law is law that has developed over time through judicial decisions in individual contract disputes and claims. Courts in the United States have issued rulings in contract-related cases for centuries, creating a body of precedent that serves as the foundation of contract law. Thus, by the early twentieth century, tens of thousands of contract disputes had been submitted to the courts for resolution, and the published opinions written by judges, if collected in one place, would have filled dozens of bookshelves. Clearly this mass of material was too unwieldy for efficient use. A similar problem also had developed in the other leading branches of the common law.

The Restatement (Second) of Contracts

Disturbed by the plethora of cases, the difficulty in finding a specific case, and the resulting uncertainty of the law, a group of prominent American judges, lawyers, and law teachers founded the American Law Institute (ALI) in 1923 to attempt to clarify, simplify, and improve the law. One of the ALI’s first projects, and ultimately one of its most successful, was the drafting of the Restatement of the Law of Contracts, completed in 1932. A revision—the Restatement (Second) of Contracts—was undertaken in 1964 and completed in 1979. Hereafter, references to “the Restatement” pertain to the Restatement (Second) of Contracts.

The Restatements (they also exist in the other fields of law besides contracts, including torts and property) are detailed analyses of the decided cases in each field. Encompassing a wide range of disciplines, the Restatements summarize the common law principles as they have evolved across the majority of U.S. jurisdictions. In addition to presenting common law doctrines, the Restatements offer commentary, hypothetical scenarios illustrating the application of these principles, and summaries of relevant cases.

The Restatement won prompt respect in the courts and has been cited in innumerable cases. The Restatements are not authoritative, in the sense that they are not actual judicial precedents; but they are nevertheless weighty interpretive texts, and judges frequently look to them for guidance. They are as close to “black letter” rules of law as exist anywhere in the American common-law legal system.

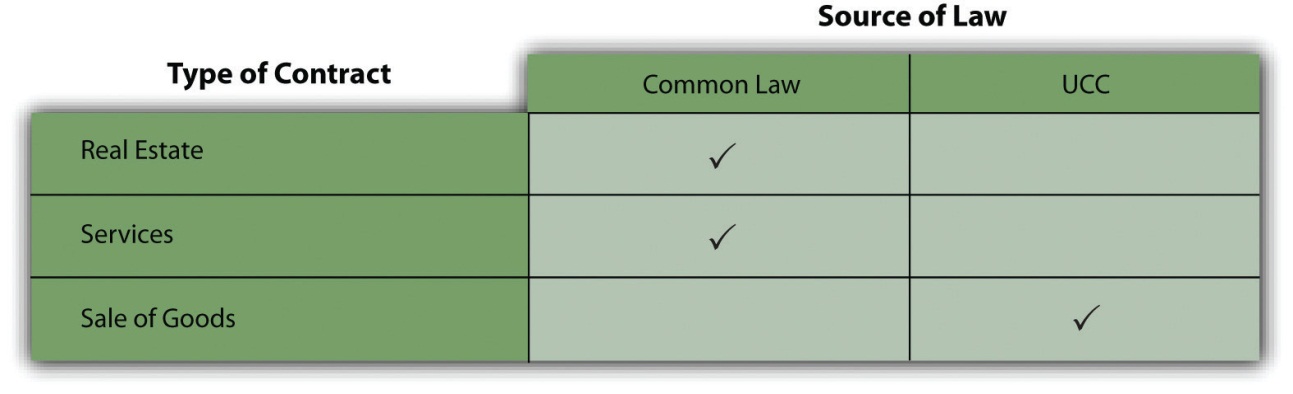

Today, common law or case law (the terms are mostly synonymous) governs contracts for the sale of real estate and services. “Services” refers to acts or deeds (like plumbing, drafting documents, driving a car) as opposed to the sale of property.

Statutory Law: The Uniform Commercial Code

Common-law contract principles govern contracts for real estate and services. Because of the historical development of the English legal system, contracts for the sale of goods came to be governed by a different body of legal rules. In its modern American manifestation, that body of rules is an important statute: the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC), especially Article 2, which deals with the sale of goods.

History of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC)

In addition to the overabundance of cases that was discussed above, in commercial transactions there was an another barrier to legal efficiency in contracting. The development of the common law through judicial interpretation meant that the law varied, sometimes greatly, from state to state. This was a serious impediment to business as the American economy became nationwide during the twentieth century. Although there had been some uniform laws concerned with commercial deals—including the Uniform Sales Act, first published in 1906—few were widely adopted and none nationally.

Enter the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC). The UCC is a model law developed by the ALI and the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws; it has been adopted in one form or another by the legislatures in all fifty states, the District of Columbia, and the American territories. It is a “national” law not enacted by Congress—it is not federal law but uniform state law.

Initial drafting of the UCC began in 1942 and was ten years in the making, involving the efforts of hundreds of practicing lawyers, law teachers, and judges. A final draft, promulgated by the ALI, was endorsed by the American Bar Association and published in 1951. Various revisions followed in different states, threatening the uniformity of the UCC. The ALI responded by creating a permanent editorial board to oversee future revisions. In one or another of its various revisions, the UCC has been adopted in whole or in part in all American jurisdictions. The UCC is now a basic law of relevance to every business and business lawyer in the United States, even though it is not entirely uniform because different states have adopted it at various stages of its evolution—an evolution that continues still.

Organization of the UCC

The UCC consists of nine major substantive articles, each dealing with separate though related subjects. The articles are as follows:

- Article 1: General Provisions

- Article 2/2A: Sales and Leases of Goods

- Article 3: Commercial Paper

- Article 4/4A: Bank Deposits and Collections and Funds Transfers

- Article 5: Letters of Credit

- Article 6: Bulk Transfers

- Article 7: Warehouse Receipts, Bills of Lading, and Other Documents of Title

- Article 8: Investment Securities

- Article 9: Secured Transactions

Article 2 deals with the sale of goods, which the UCC defines as “all things…which are movable at the time of identification to the contract for sale other than the money in which the price is to be paid.” As these sales/leases are accomplished by contracting, agreements covered by Articles 2/2A which relate to the present or future sale of goods also make up the law of contracts.

Figure 5.1 Sources of Law

International Sales Law

The Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods

A Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (CISG) was approved in 1980 at a diplomatic conference in Vienna. (A convention is a preliminary agreement that serves as the basis for a formal treaty.) The CISG has been adopted by more than forty countries, including the United States.

The CISG is significant for three reasons. First, it is a uniform law governing the sale of goods—in effect, an international Uniform Commercial Code. The major goal of the drafters was to produce a uniform law acceptable to countries with different legal, social, and economic systems. Second, although provisions in the CISG are generally consistent with the UCC, there are significant differences. For instance, under the CISG, consideration is not required to form a contract, and there is no Statute of Frauds (a requirement that certain contracts be evidenced by a writing). Third, the CISG represents the first attempt by the U.S. Senate to reform the private law of business through its treaty powers, for the CISG preempts the UCC. The CISG is not mandatory; parties to an international contract for the sale of goods may choose to have their agreement governed by different law, perhaps the UCC, or, say, Japanese contract law. The CISG does not apply to contracts for the sale of (1) ships or aircraft, (2) electricity, or (3) goods bought for personal, family, or household use, nor does it apply (4) where the party furnishing the goods does so only incidentally to the labor or services part of the contract.

Check Your Understanding

the body of law derived from judicial decisions rather than from statutes or constitutions

a legal treatise from the second series of the Restatements of the Law which seeks to inform judges and lawyers about general principles of contract common law

in common law legal systems, refers to well-established legal rules that are no longer subject to reasonable dispute

a set of statutes governing the conduct of business, sales, warranties, negotiable instruments, loans secured by personal property and other commercial matters

a benefit that is of value to both parties, which must be bargained for between the parties and is the essential reason for a party entering into a contract