Chapter 2 – Courts and the Legal Process

2.6 How a Case Proceeds in Court

In this section, we consider how lawsuits are begun and how they make their way through the Courts. Courts do not reach out for cases. Instead, cases are brought to them, usually when an attorney files a case with the right court on behalf of a person that believes they have suffered a legal harm. Once correctly filed, the case will proceed through the various processes designed with due process concerns in mind. In the United States, we have an adversarial court process, which means that the parties oppose each other throughout the litigation, with the goal of “winning” their case. The lawyer, if one is employed by the litigant, serves as an advocate for the client’s claim. Their duty would be to shape the evidence and the argument—the line of reasoning about the evidence—to advance his client’s cause and persuade the court of its rightness. The lawyer for the opposing party will be doing the same thing, of course, for her client. The judge (or, if one is sitting, the jury) must sort out the facts and reach a decision from this cross-fire of evidence and argument. The litigant that initiated the case has the burden of proof, which in a civil trial is generally a “preponderance of the evidence” which means that the plaintiff’s evidence must outweigh whatever evidence the defendant can muster that casts doubts on the plaintiff’s claim. Let’s review the process in more depth below.

Initial Pleadings and Process

Complaint and Summons

Beginning a lawsuit is simple and is spelled out in the rules of procedure by which each court system operates. A civil plaintiff begins a lawsuit by filing a complaint—a document clearly explaining the grounds for suit—with the clerk of the court. A complaint will have several key components as it serves as an initial pleading and sets the stage for the remainder of the litigation. The complaint will have a caption which indicates the parties to the lawsuit, the court the case is filed in, and the type of case, as well as identifying information called a docket number so the case can be tracked. The complaint must establish that the court has jurisdiction to decide the controversy, and the complaint must state the nature of the plaintiff’s claim and the relief that is being asked for (usually an award of money, but sometimes an injunction, or a declaration of legal rights). In addition, the complaint is signed, attesting to its truthfulness. Once the complaint is filed with the court, the defendant must be served with the complaint and summons. The summons is a court document stating the name of the plaintiff and their attorney and directing the defendant to respond to the complaint within a fixed time period.

Jurisdiction and Venue

As the complaint must establish that the Court has the power to decide the case, the complaint must be filed in a correct location. The Court must have subject matter jurisdiction over the claim in the complaint, and the complaint must be filed in the proper geographic location – called venue.

Service of Process

As stated above, the defendant in the case must be “served”—that is, must receive notice that he has been sued. This delivery of notice is referred to as service of process. Service can be done by physically presenting the defendant with a copy of the summons and complaint. But sometimes the defendant is difficult to find (or deliberately avoids the marshal or other process server). The rules spell out a variety of ways by which individuals and corporations can be served. These include using U.S. Postal Service certified mail or serving someone already designated to receive service of process. A corporation or partnership, for example, is often required by state law to designate a “registered agent” for purposes of getting public notices or receiving a summons and complaint.

Timing of Filing

The timing of the filing is important. Almost every possible legal complaint is governed by a federal or state statute of limitations, which requires a lawsuit to be filed within a certain period of time. For example, in many states a lawsuit for injuries resulting from an automobile accident must be filed within two years of the accident or the plaintiff forfeits his right to proceed. As noted earlier, making a correct initial filing, and including the required components of a complaint in a court that has subject matter jurisdiction is critical to avoiding statute of limitations problems.

Answer and Affirmative Defenses

Once a complaint is appropriately served, the Defendant in a lawsuit files an answer. The answer is the initial pleading of the defendant that is a written response to the plaintiff’s claims. The answer typically either ‘admits’ or ‘denies’ the allegations made by the plaintiff. Admitted allegations are accepted as true, while denied allegations require the plaintiff to prove their case. Therefore, most allegations are denied. The answer may also include “affirmative defenses,” which are legal reasons that, if proven, would excuse the defendant from liability. Affirmative defenses can also introduce new facts or principles to justify the defendant’s actions. As an example, the issue of the statute of limitations, referenced above, could be an affirmative defense if by defendant’s calculations the plaintiff did not file their complaint in time. The answer may also include counterclaims against the plaintiff or cross-claims against other defendants. The answer is filed within a specific time frame governed by the rules of the court in which the complaint was filed.

Motions and Discovery

The early phases of a civil action are characterized by many different kinds of motions and the exchange of mutual fact-finding between the parties that is known as discovery. After the pleadings, the parties may make various motions, which are requests to the judge to rule on legal issues in the case. Motions in the early stages of a lawsuit usually aim to dismiss the lawsuit, to have it moved to another venue, or to compel the other party to act in certain ways during the discovery process.

Motions

In litigation, a “motion” is a formal request made by one party to a lawsuit (the moving party) asking the court to take a specific action or make a particular decision. If a party wins a motion, or loses one for that matter, it can streamline the legal issues in the case substantially.

Motions to Dismiss at Pleadings Stage

A complaint and subsequent pleadings are usually quite general and give little detail. But in some instances, a case can be decided based on the pleadings alone. For example, if the defendant fails to answer the complaint, the Plaintiff can move for the court to enter a default judgment, awarding the plaintiff what they seek.

A defendant that believes that the complaint is defective can move to dismiss the complaint on the grounds that the plaintiff failed to “state a claim on which relief can be granted,” or on the basis that there is no subject matter jurisdiction for the court chosen by the plaintiff, or on the basis that there is no personal jurisdiction over the defendant. The defendant is saying, in effect, that even if all the plaintiff’s allegations are true, they do not amount to a legal claim that can be heard by the court.

Motion for Summary Judgment

A “motion for summary judgment” is a legal request made by a party to a lawsuit, asking the court to decide the case or specific claims in their favor without going to trial. This motion is typically filed after the parties have conducted discovery (summarized below) such that key facts in the case are known to both parties. If there is no triable question of fact or law, there is no reason to have a trial with a jury, and a judge could simply decide the case.

Discovery

If the claim made by the plaintiff involves a factual dispute, the case will usually involve some degree of discovery, where each party tries to get as much information out of the other party as the discovery rules allow. In a civil action, the parties are entitled to learn the facts of the case before trial. The basic idea is to help the parties determine what the evidence might be, who the potential witnesses are, and what specific issues are relevant. Full discovery helps determine which cases should genuinely go to trial to be heard by a jury, and which cases can be amicably settled. It helps each side understand the strengths and weaknesses of their opponent’s claims and defenses. There are several methods by which discovery can take place, the most common of which are listed here:

| Interrogatories | Written questions that one party sends to the other which the recipient is required to answer under oath. Interrogatories seek factual information, legal contentions, or details about the parties’ claims and defenses. |

| Depositions | Oral testimony given under oath outside of court, typically recorded by a court reporter. Parties or witnesses answer questions posed by attorneys. Depositions help gather firsthand accounts and allow each party to assess credibility. |

| Requests for Production | Formal requests for specific documents, electronically stored information, or tangible items relevant to the case. These requests seek evidence such as contracts, emails, reports, and records. |

| Requests for Admission | Written requests asking the opposing party to admit or deny specific statements or facts. Admissions streamline the issues by eliminating the need to prove certain facts at trial. An allegation that was denied in the pleading stage of the lawsuit might now be admitted after full discovery. |

| Physical and Mental Examinations | When a person’s physical or mental condition is relevant to the case, such as in a personal injury case, a court may order an examination by a qualified medical professional. |

The lawyers, not the court, run the discovery process. For example, one party simply makes a written demand, stating the time at which the deposition will take place or the type of documents it wishes to inspect and make copies of. A party unreasonably resisting discovery methods (whether depositions, written interrogatories, or requests for documents) can be challenged using a motion to compel discovery as judges can be brought into the process to push reluctant parties to make more disclosure or to protect a party from irrelevant or unreasonable discovery requests. For example, the party receiving the discovery request can apply to the court for a protective order if it can show that the demand is for privileged material (e.g., a party’s lawyers’ records are not open for inspection) or that the demand was made to harass the opponent. In complex cases between companies, the discovery of documents can run into tens of millions of pages and can take years. Depositions can consume days or even weeks of an executive’s time.

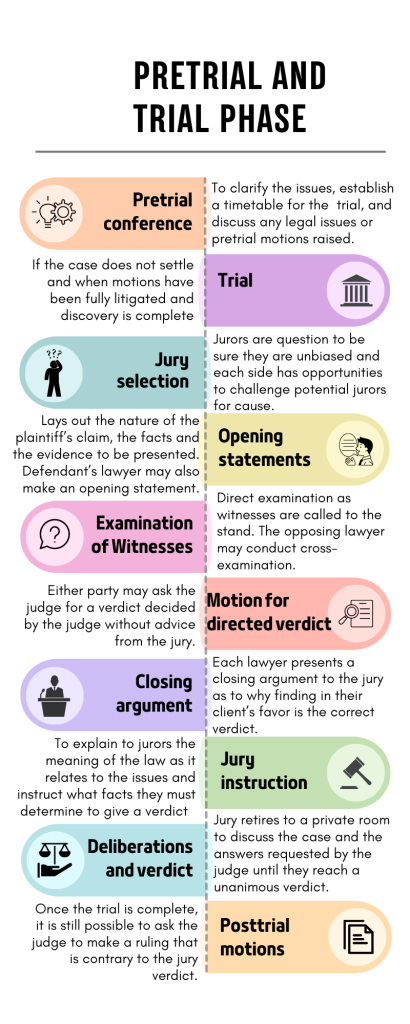

The Pretrial and Trial Phase

Once the discovery period is complete, the case moves on to trial if it has not been settled. Most cases are settled before this stage; perhaps 85 percent of all civil cases end before trial, and more than 90 percent of criminal prosecutions end with a guilty plea.

Pretrial Conference

Depending on the nature and complexity of the case, the court may hold a pretrial conference to clarify the issues and establish a timetable for the upcoming trial, as well as discuss any legal issues or pretrial motions raised in the case. The pretrial conference may also be used as a settlement conference to see if the parties can work out their differences and avoid trial altogether. If the judge believes that settlement is a possibility, the judge will explore the strengths and weaknesses of each party’s case with the attorneys. The parties may decide that it is more prudent or efficient to settle than to risk going to trial.

Trial

If the case does not settle, motions have been fully litigated, and discovery is complete, the case will be scheduled for trial.

Jury Selection

At trial, the first order of business is to select a jury. The judge and sometimes the lawyers are permitted to question the jurors to be sure that they are unbiased. This questioning is known as the voir dire (pronounced vwahr-DEER). This is an important process, and a great deal of thought goes into selecting the jury, especially in high-profile cases. A jury panel can be as few as six persons, or as many as twelve, with alternates selected and sitting in court in case one of the jurors is unable to continue. In a long trial, having alternates is essential; even in shorter trials, most courts will have at least two alternate jurors.

In both criminal and civil trials, each side has opportunities to challenge potential jurors for cause. For example, in the Robinsons’ case against Audi, the attorneys representing Audi will want to know if any prospective jurors have ever owned an Audi, what their experience has been, and if they had a similar problem (or worse) with their Audi that was not resolved to their satisfaction. If so, the defense attorney could well believe that such a juror has a potential for a bias against her client. In that case, she could use a for cause challenge, explaining to the judge the basis for her challenge. The judge, at her discretion, could either accept the for-cause reason or reject it.

Even if an attorney cannot articulate a for-cause reason acceptable to the judge, she may use one of several peremptory challenges that most states (and the federal system) allow. A trial attorney with many years of experience may have a sixth sense about a potential juror and, in consultation with the client, may decide to use a peremptory challenge to avoid having that juror on the panel.

Opening Statements

After the jury is sworn and seated, the plaintiff’s lawyer makes an opening statement, laying out the nature of the plaintiff’s claim, the facts of the case as the plaintiff sees them, and the evidence that the lawyer will present. The defendant’s lawyer may also make an opening statement or may reserve his right to do so at the end of the plaintiff’s case.

Examination of Witnesses

Once opening statements are completed, the plaintiff’s lawyer then calls witnesses and presents the physical evidence that is relevant to her proof, called the plaintiff’s case in chief. The initial questioning of witnesses by the party that calls them to the stand is a direct examination. Testimony at trial is usually far from a smooth narration. The rules of evidence (that govern the kinds of testimony and documents that may be introduced at trial) and the question-and-answer format tend to make the presentation of evidence choppy and difficult to follow.

Anyone who has watched an actual televised trial or a television melodrama featuring a trial scene will appreciate the nature of the trial itself: witnesses are asked questions about a number of issues that may or may not be related, the opposing lawyer will frequently object to the question or the form in which it is asked, and the jury may be sent from the room while the lawyers argue at the bench before the judge.

After direct examination of each witness is over, the opposing lawyer may conduct cross-examination. The formal rules of direct testimony are then relaxed, and the cross-examiner may probe the witness more informally, asking questions that may not seem immediately relevant. The opposing attorney may become harsh trying to cast doubt on a witness’s credibility, trying to trip her up and show that the answers she gave are false or not to be trusted. This use of cross-examination, along with the requirement that the witness must respond to questions that are at all relevant to the questions raised by the case, distinguishes common-law courts from those of authoritarian regimes around the world.

Following cross-examination, the plaintiff’s lawyer may then question the witness again: this is called redirect examination and is used to demonstrate that the witness’s original answers were accurate and to show that any implications otherwise, suggested by the cross-examiner, were unwarranted. The cross-examiner may then engage the witness in recross-examination, and so on. The process usually stops after cross-examination or redirect.

During the trial, the judge’s chief responsibility is to see that the trial is fair to both sides. One big piece of that responsibility is to rule on the admissibility of evidence. A judge may rule that a particular question is out of order—that is, not relevant or appropriate—or that a given document is irrelevant. Where the attorney is convinced that a particular witness, a particular question, or a particular document (or part thereof) is critical to her case, she may preserve an objection to the court’s ruling by saying “exception,” in which case the court stenographer will note the exception, and the attorney may raise these issues on appeal should there be one.

At the end of the plaintiff’s case, the defendant presents his case in chief, following the same procedure just outlined. The plaintiff is then entitled to present rebuttal witnesses, if necessary, to deny or argue with the evidence the defendant has introduced. The defendant in turn may present “surrebuttal” witnesses.

Motion for Directed Verdict

When all testimony has been introduced, either party may ask the judge for a motion for directed verdict—a verdict decided by the judge without advice from the jury. This motion may be granted if the plaintiff has failed to introduce evidence that is legally sufficient to meet her burden of proof or if the defendant has failed to do the same on issues on which she has the burden of proof. (For example, the plaintiff alleges that the defendant owes him money and introduces a signed promissory note. The defendant cannot show that the note is invalid. The defendant must lose the case unless he can show that the debt has been paid or otherwise discharged.)

The defendant can move for a directed verdict at the close of the plaintiff’s case, but the judge will usually wait to hear the entire case until deciding whether to do so. Directed verdicts are not usually granted, since it is the jury’s job to determine the facts in dispute.

Closing Argument

If the judge refuses to grant a directed verdict, each lawyer will then present a closing argument to the jury (or, if there is no jury, to the judge alone). The closing argument is used to tie up the loose ends, as the attorney tries to bring together various seemingly unrelated facts into a story that will make sense to the jury, and make the argument as to why finding in their client’s favor is the correct verdict.

Jury Instruction

After closing arguments, the judge will instruct the jury. The purpose of jury instruction is to explain to the jurors the meaning of the law as it relates to the issues they are considering and to tell the jurors what facts they must determine if they are to give a verdict for one party or the other. Each lawyer will have prepared a set of written instructions that she hopes the judge will give to the jury. These will be tailored to advance her client’s case. Many a verdict has been overturned on appeal because a trial judge has wrongly instructed the jury. The judge will carefully determine which instructions to give and often will use a set of pattern instructions provided by the state bar association or the supreme court of the state. These pattern jury instructions are often safer because they are patterned after language that appellate courts have used previously, and appellate courts are less likely to find reversible error in the instructions. In civil cases, the plaintiff has the burden of proof, typically of proving their claim by a preponderance of the evidence. The jury will be instructed on what this means and how to apply this burden of proof.

Deliberations and Verdict

After all instructions are given, the jury will retire to a private room and discuss the case and the answers requested by the judge for as long as it takes to reach a unanimous verdict. In New Jersey, civil cases are not required to be unanimous. Instead, only 5/6 of the jurors need to agree on a verdict. If the jury cannot reach a decision, this is called a hung jury, and the case will have to be retried. When a jury does reach a verdict, it delivers it in court with both parties and their lawyers present. The jury is then discharged, and control over the case returns to the judge. (If there is no jury, the judge will usually announce in a written opinion his findings of fact and how the law applies to those facts. Juries just announce their verdicts and do not state their reasons for reaching them.)

Posttrial Motions

Once the trial is complete, it is still possible to ask the judge to make a ruling that is contrary to the jury verdict. The losing party at trial is allowed to ask the judge for a new trial or for a judgment notwithstanding the verdict (often called a JNOV, from the Latin non obstante veredicto).

Motion for a New Trial: A motion for a new trial is a request made by a party after a trial has concluded, asking the court to set aside the jury’s verdict and order a new trial. This motion is typically based on perceived errors or irregularities that occurred during the trial that may have influenced the outcome. The party seeking a new trial asserts that some legal error, procedural mistake, or unfairness occurred during the trial process that warrants another opportunity to present their case.

Judgment Notwithstanding the Verdict (JNOV): A JNOV is a motion that challenges the jury’s verdict after trial. It is typically filed by the losing party, arguing that the jury’s verdict was not supported by sufficient evidence or was legally erroneous. In other words, the party contends that even if all the evidence is viewed in the light most favorable to the winning party, no reasonable jury could have reached the verdict that was reached.

Post-trial, a party may renew a prior motion for directed verdict. A judge who decides that a directed verdict is appropriate will usually wait to see what the jury’s verdict is. If it is favorable to the party the judge thinks should win, she can rely on that verdict. If the verdict is for the other party, the judge can grant the motion for JNOV. This is a safer way to proceed because if the judge is reversed on appeal, a new trial is not necessary. The jury’s verdict always can be restored, whereas without a jury verdict (as happens when a directed verdict is granted before the case goes to the jury), the entire case must be presented to a new jury.

Case 2.2

Ferlito v. Johnson & Johnson Products, Inc., 771 F. Supp. 196 (U.S. District Ct., Eastern District of Michigan 1991)

GADOLA, J.

Plaintiffs Susan and Frank Ferlito, husband and wife, attended a Halloween party in 1984 dressed as Mary (Mrs. Ferlito) and her little lamb (Mr. Ferlito). Mrs. Ferlito had constructed a lamb costume for her husband by gluing cotton batting manufactured by defendant Johnson & Johnson Products (“JJP”) to a suit of long underwear. She had also used defendant’s product to fashion a headpiece, complete with ears. The costume covered Mr. Ferlito from his head to his ankles, except for his face and hands, which were blackened with Halloween paint. At the party Mr. Ferlito attempted to light his cigarette by using a butane lighter. The flame passed close to his left arm, and the cotton batting on his left sleeve ignited. Plaintiffs sued defendant for injuries they suffered from burns which covered approximately one-third of Mr. Ferlito’s body.

Following a jury verdict entered for plaintiffs November 2, 1989, the Honorable Ralph M. Freeman entered a judgment for plaintiff Frank Ferlito in the amount of $555,000 and for plaintiff Susan Ferlito in the amount of $ 70,000. Judgment was entered November 7, 1989. Subsequently, on November 16, 1989, defendant JJP filed a timely motion for judgment notwithstanding the verdict pursuant to Fed.R.Civ.P. 50(b) or, in the alternative, for new trial. Plaintiffs filed their response to defendant’s motion December 18, 1989; and defendant filed a reply January 4, 1990. Before reaching a decision on this motion, Judge Freeman died. The case was reassigned to this court April 12, 1990.

MOTION FOR JUDGMENT NOTWITHSTANDING THE VERDICT

Defendant JJP filed two motions for a directed verdict, the first on October 27, 1989, at the close of plaintiffs’ proofs, and the second on October 30, 1989, at the close of defendant’s proofs. Judge Freeman denied both motions without prejudice. Judgment for plaintiffs was entered November 7, 1989; and defendant’s instant motion, filed November 16, 1989, was filed in a timely manner.

The standard for determining whether to grant a j.n.o.v. is identical to the standard for evaluating a motion for directed verdict:

In determining whether the evidence is sufficient, the trial court may neither weigh the evidence, pass on the credibility of witnesses nor substitute its judgment for that of the jury. Rather, the evidence must be viewed in the light most favorable to the party against whom the motion is made, drawing from that evidence all reasonable inferences in his favor. If after reviewing the evidence…the trial court is of the opinion that reasonable minds could not come to the result reached by the jury, then the motion for j.n.o.v. should be granted.

To recover in a “failure to warn” product liability action, a plaintiff must prove each of the following four elements of negligence: (1) that the defendant owed a duty to the plaintiff, (2) that the defendant violated that duty, (3) that the defendant’s breach of that duty was a proximate cause of the damages suffered by the plaintiff, and (4) that the plaintiff suffered damages.

To establish a prima facie case that a manufacturer’s breach of its duty to warn was a proximate cause of an injury sustained, a plaintiff must present evidence that the product would have been used differently had the proffered warnings been given.1[Citations omitted] In the absence of evidence that a warning would have prevented the harm complained of by altering the plaintiff’s conduct, the failure to warn cannot be deemed a proximate cause of the plaintiff’s injury as a matter of law. [In accordance with procedure in a diversity of citizenship case, such as this one, the court cites Michigan case law as the basis for its legal interpretation.]

…

A manufacturer has a duty “to warn the purchasers or users of its product about dangers associated with intended use.” Conversely, a manufacturer has no duty to warn of a danger arising from an unforeseeable misuse of its product. [Citation] Thus, whether a manufacturer has a duty to warn depends on whether the use of the product and the injury sustained by it are foreseeable. Gootee v. Colt Industries Inc., 712 F.2d 1057, 1065 (6th Cir. 1983); Owens v. Allis-Chalmers Corp., 414 Mich. 413, 425, 326 N.W.2d 372 (1982). Whether a plaintiff’s use of a product is foreseeable is a legal question to be resolved by the court. Trotter, supra. Whether the resulting injury is foreseeable is a question of fact for the jury.2 Thomas v. International Harvester Co., 57 Mich. App. 79, 225 N.W.2d 175 (1974).

In the instant action no reasonable jury could find that JJP’s failure to warn of the flammability of cotton batting was a proximate cause of plaintiffs’ injuries because plaintiffs failed to offer any evidence to establish that a flammability warning on JJP’s cotton batting would have dissuaded them from using the product in the manner that they did.

Plaintiffs repeatedly stated in their response brief that plaintiff Susan Ferlito testified that “she would never again use cotton batting to make a costume…” However, a review of the trial transcript reveals that plaintiff Susan Ferlito never testified that she would never again use cotton batting to make a costume. More importantly, the transcript contains no statement by plaintiff Susan Ferlito that a flammability warning on defendant JJP’s product would have dissuaded her from using the cotton batting to construct the costume in the first place. At oral argument counsel for plaintiffs conceded that there was no testimony during the trial that either plaintiff Susan Ferlito or her husband, plaintiff Frank J. Ferlito, would have acted any different if there had been a flammability warning on the product’s package. The absence of such testimony is fatal to plaintiffs’ case; for without it, plaintiffs have failed to prove proximate cause, one of the essential elements of their negligence claim.

In addition, both plaintiffs testified that they knew that cotton batting burns when it is exposed to flame. Susan Ferlito testified that she knew at the time she purchased the cotton batting that it would burn if exposed to an open flame. Frank Ferlito testified that he knew at the time he appeared at the Halloween party that cotton batting would burn if exposed to an open flame. His additional testimony that he would not have intentionally put a flame to the cotton batting shows that he recognized the risk of injury of which he claims JJP should have warned. Because both plaintiffs were already aware of the danger, a warning by JJP would have been superfluous. Therefore, a reasonable jury could not have found that JJP’s failure to provide a warning was a proximate cause of plaintiffs’ injuries.

The evidence in this case clearly demonstrated that neither the use to which plaintiffs put JJP’s product nor the injuries arising from that use were foreseeable. Susan Ferlito testified that the idea for the costume was hers alone. As described on the product’s package, its intended uses are for cleansing, applying medications, and infant care. Plaintiffs’ showing that the product may be used on occasion in classrooms for decorative purposes failed to demonstrate the foreseeability of an adult male encapsulating himself from head to toe in cotton batting and then lighting up a cigarette.

ORDER

NOW, THEREFORE, IT IS HEREBY ORDERED that defendant JJP’s motion for judgment notwithstanding the verdict is GRANTED.

IT IS FURTHER ORDERED that the judgment entered November 2, 1989, is SET ASIDE.

IT IS FURTHER ORDERED that the clerk will enter a judgment in favor of the defendant JJP.

Case questions

- The opinion focuses on proximate cause. As we will see when we study tort law, a negligence case cannot be won unless the plaintiff shows that the defendant has breached a duty and that the defendant’s breach has actually and proximately caused the damage complained of. What, exactly, is the alleged breach of duty by the defendant here?

- Explain why Judge Gadola reasoning that JJP had no duty to warn in this case. After this case, would they then have a duty to warn, knowing that someone might use their product in this way?

Judgment, Appeal, and Execution

Judgment or Order

At the end of a trial, the judge will enter an order that makes findings of fact (often with the help of a jury) and conclusions of law. The judge will also make a judgment as to what relief or remedy should be given. Often it is an award of money damages to one of the parties. The losing party may ask for a new trial at this point or within a short period of time following. Once the trial judge denies any such request, the judgment—in the form of the court’s order—is final.

Appeal

If the loser’s motion for a new trial or a JNOV is denied, the losing party may appeal but must ordinarily post a bond sufficient to ensure that there are funds to pay the amount awarded to the winning party. In an appeal, the appellant aims to show that there was some prejudicial error committed by the trial judge. There will be errors, of course, but the errors must be significant (i.e., not harmless). The basic idea is for an appellate court to ensure that a reasonably fair trial was provided to both sides. Enforcement of the court’s judgment—an award of money, an injunction—is usually stayed (postponed) until the appellate court has ruled. As noted earlier, the party making the appeal is called the appellant, and the party defending the judgment is the appellee (or in some courts, the petitioner and the respondent).

During the trial, the losing party may have objected to certain procedural decisions by the judge. In compiling a record on appeal, the appellant needs to show the appellate court some examples of mistakes made by the judge—for example, having erroneously admitted evidence, having failed to admit proper evidence that should have been admitted, or having wrongly instructed the jury. The appellate court must determine if those mistakes were serious enough to amount to prejudicial error.

Appellate and trial procedures are different. The appellate court does not hear witnesses or accept evidence. It reviews the record of the case—the transcript of the witnesses’ testimony and the documents received into evidence at trial—to try to find a legal error on a specific request of one or both of the parties. The parties’ lawyers prepare briefs (written statements containing the facts in the case), the procedural steps taken, and the argument or discussion of the meaning of the law and how it applies to the facts. After reading the briefs on appeal, the appellate court may dispose of the appeal without argument, issuing a written opinion that may be very short or many pages. Often, though, the appellate court will hear oral argument. (This can be months, or even more than a year after the briefs are filed.) Each lawyer is given a short period of time, usually no more than thirty minutes, to present his client’s case. The lawyer rarely gets a chance for an extended statement because he is usually interrupted by questions from the judges. Through this exchange between judges and lawyers, specific legal positions can be tested and their limits explored.

Depending on what it decides, the appellate court will affirm the lower court’s judgment, modify it, reverse it, or remand it to the lower court for retrial or other action directed by the higher court. The appellate court itself does not take specific action in the case; it sits only to rule on contested issues of law. The lower court must issue the final judgment in the case. As we have already seen, there is the possibility of appealing from an intermediate appellate court to the state supreme court in twenty-nine states and to the U.S. Supreme Court from a ruling from a federal circuit court of appeal. In cases raising constitutional issues, there is also the possibility of appeal to the Supreme Court from the state courts.

Like trial judges, appellate judges must follow previous decisions, or precedent. But not every previous case is a precedent for every court. Lower courts must respect appellate court decisions, and courts in one state are not bound by decisions of courts in other states. State courts are not bound by decisions of federal courts, except on points of federal law that come from federal courts within the state or from a federal circuit in which the state court sits. A state supreme court is not bound by case law in any other state. But a supreme court in one state with a type of case it has not previously dealt with may find persuasive reasoning in decisions of other state supreme courts.

Federal district courts are bound by the decisions of the court of appeals in their circuit, but decisions by one circuit court are not precedents for courts in other circuits. Federal courts are also bound by decisions of the state supreme courts within their geographic territory in diversity jurisdiction cases. All courts are bound by decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court, except the Supreme Court itself, which seldom reverses itself but on occasion has overturned its own precedents.

Not everything a court says in an opinion is a precedent. Strictly speaking, only the exact holding is binding on the lower courts. A holding is the theory of the law that applies to the particular circumstances presented in a case. The courts may sometimes declare what they believe to be the law with regard to points that are not central to the case being decided. These declarations are called dicta (the singular, dictum), and the lower courts do not have to give them the same weight as holdings.

Execution

When a party has no more possible appeals, it usually pays up voluntarily. If not voluntarily, then the losing party’s assets can be seized or its wages or other income garnished to satisfy the judgment. This is called executing the judgment. If the final judgment is an injunction, failure to follow its dictates can lead to a contempt citation, with a fine or jail time imposed.

Student Video of the Litigation Timeline

Footnotes

Footnotes

1 By “prima facie case,” the court means a case in which the plaintiff has presented all the basic elements of the cause of action alleged in the complaint. If one or more elements of proof are missing, then the plaintiff has fallen short of establishing a prima facie case, and the case should be dismissed (usually on the basis of a directed verdict).

2 Note the division of labor here: questions of law are for the judge, while questions of “fact” are for the jury. Here, “foreseeability” is a fact question, while the judge retains authority over questions of law. The division between questions of fact and questions of law is not an easy one, however.

the first document filed with the court (actually with the County Clerk or Clerk of the Court) by a person or entity claiming legal rights against another

a court document stating the name of the plaintiff and their attorney and directing the defendant to respond to the complaint within a fixed time period

the jurisdiction of a court over the subject, type, or cause of action of a case that allows the court to issue a binding judgment

the specific geographic location or district where a legal case is heard or tried

the delivery of copies of legal documents such as summons, complaint, subpoena, order to show cause (order to appear and argue against a proposed order), writs, notice to quit the premises, and certain other documents, usually by personal delivery to the defendant or other person to whom the documents are directed

a defendant's written response to a plaintiff's initial court filing (called a complaint or petition)

statements in a response to a civil lawsuit which excuse or justify the behavior on which the lawsuit is based.

a formal investigation—governed by court rules—conducted before trial by all parties to a lawsuit to find evidence that can be used to present claims or defenses at trial, to find out what evidence other parties will use at trial, and to support its position during settlement negotiations

a formal request made by one party to a lawsuit (the moving party) asking the court to take a specific action or make a particular decision

the right to dismiss or excuse a potential juror during jury selection without having to give a reason

a legal request made by a party to a lawsuit, asking the court to decide the case or specific claims in their favor without going to trial

written questions that one party sends to the other which the recipient is required to answer under oath

oral testimony given under oath outside of court, typically recorded by a court reporter

formal requests for specific documents, electronically stored information, or tangible items relevant to the case

written requests asking the opposing party to admit or deny specific statements or facts

a court-ordered examination by a qualified medical professional of a person's physical or mental condition

a proceeding attended by the parties to an action and a judge or magistrate and held at a party's request or on the judge's initiative for the purpose of focusing the issues, making discovery, entering into stipulations, obtaining rulings, and dealing with any matters that may facilitate fair and efficient disposition of the case including settlement

French for "to speak the truth," this is the questioning in court of prospective jurors by a judge or attorneys

a party's request that the judge dismiss a potential juror from serving on a jury by providing a valid legal reason why he shouldn't serve

the right to dismiss or excuse a potential juror during jury selection without having to give a reason

a statement made by an attorney or self-represented party at the beginning of a trial before evidence is introduced

initial questioning of witness by the party calling them to the stand

the opportunity for the attorney (or an unrepresented party) to ask questions in court of a witness who has testified in a trial on behalf of the opposing party

an additional direct examination of a witness following cross-examination

examination of a witness after redirect examination

a ruling by a judge, typically made after the plaintiff has presented all of its evidence but before the defendant puts on its case, that awards judgment to the defendant

a jury's decision after a trial, which becomes final when accepted by the judge

the final argument by an attorney on behalf of the client after all evidence has been produced for both sides

the judge explains to the jurors the meaning of the law as it relates to the issues they are considering and tells them what facts they must determine in order to give a verdict

a trial court for federal cases in a court district, which is all or a portion of a state

the act of finishing, carrying out, or performing as required, as in fulfilling one's obligations under a contract, plan, or court order