Chapter 5 – Introduction to Contract Law

5.4 Classifications of Contracts

Contracts are classified in different ways. Ascribing a classification to a contract helps to learn about that contract, and potential rights and obligations under that contract. This section will describe the primary ways that contracts are classified.

Express, Implied or Quasi Contracts

A contract is either express, implied-in-fact (implied) or imposed by the court as an implied in law contract (quasi).

Express Contract

An express contract is a contract in which the terms and conditions are explicitly stated, either orally or in writing, with the intent of both parties to enter a contract. It’s a clear and definite agreement between the parties. For example, a homeowner hires a plumber to fix a leaky hose fixture outside their house. The homeowner and the plumber have a written agreement that outlines the specific terms of the plumbing service, such as the scope of work, the cost, and the timeline for completion. Even if neither party signs the document, this would still be an express contract, as the agreement is clearly expressed in words.

Implied Contract (Implied in Fact)

An implied contract is a contract in which the agreement is not explicitly stated in words but is inferred from the conduct and actions of the parties involved. An implied contract between the homeowner and the plumber could arise if the homeowner calls the plumber and the plumber performs the work, fixing the leaky hose fixture outside the house without discussing specific terms of the agreement. Clearly, both parties intended for the plumber to be paid for any work completed, but the detailed understanding between the two parties was not directly discussed, resulting in an implied contract.

Quasi Contract

Unlike both express and implied contracts, which embody an actual agreement of the parties, a quasi contract does not arise from the agreement of the parties. In fact, there is a lack of agreement in quasi contract situations. This is why a quasi contract is an obligation said to be “imposed by law” in order to avoid unjust enrichment of one person at the expense of another. In other words, it is an obligation imposed by a judge to prevent injustice, and not a contract at all. Suppose, for example, that a local plumbing company mistakenly sends a plumber to your house, thinking it belongs to the neighbor on the next block who had called for a repair to the leaky hose outside their house. On arrival to your home, the plumber actually does find a leaking hose and fixes it while you are home. You never communicated with the plumbing company even though you saw the repair taking place. Although it is true there is no contract, the law implies a contract for the value of the material: of course you will have to pay for the service you received.

Case 5.1

Roger’s Backhoe Service, Inc. v. Nichols, 681 N.W.2d 647 (Iowa 2004)

CARTER, J.

Defendant, Jeffrey S. Nichols, is a funeral director in Muscatine.…In early 1998 Nichols decided to build a crematorium on the tract of land on which his funeral home was located. In working with the Small Business Administration, he was required to provide drawings and specifications and obtain estimates for the project. Nichols hired an architect who prepared plans and submitted them to the City of Muscatine for approval. These plans provided that the surface water from the parking lot would drain onto the adjacent street and alley and ultimately enter city storm sewers. These plans were approved by the city.

Nichols contracted with Roger’s [Backhoe Service, Inc.] for the demolition of the foundation of a building that had been razed to provide room for the crematorium and removal of the concrete driveway and sidewalk adjacent to that foundation. Roger’s completed that work and was paid in full.

After construction began, city officials came to the jobsite and informed Roger’s that the proposed drainage of surface water onto the street and alley was unsatisfactory. The city required that an effort be made to drain the surface water into a subterranean creek, which served as part of the city’s storm sewer system. City officials indicated that this subterranean sewer system was about fourteen feet below the surface of the ground.…Roger’s conveyed the city’s mandate to Nichols when he visited the jobsite that same day.

It was Nichols’ testimony at trial that, upon receiving this information, he advised…Roger’s that he was refusing permission to engage in the exploratory excavation that the city required. Nevertheless, it appears without dispute that for the next three days Roger’s did engage in digging down to the subterranean sewer system, which was located approximately twenty feet below the surface. When the underground creek was located, city officials examined the brick walls in which it was encased and determined that it was not feasible to penetrate those walls in order to connect the surface water drainage with the underground creek. As a result of that conclusion, the city reversed its position and once again gave permission to drain the surface water onto the adjacent street and alley.

[T]he invoices at issue in this litigation relate to charges that Roger’s submitted to Nichols for the three days of excavation necessary to locate the underground sewer system and the cost for labor and materials necessary to refill the excavation with compactable materials and attain compaction by means of a tamping process.…The district court found that the charges submitted on the…invoices were fair and reasonable and that they had been performed for Nichols’ benefit and with his tacit approval.…

The court of appeals…concluded that a necessary element in establishing an implied-in-fact contract is that the services performed be beneficial to the alleged obligor. It concluded that Roger’s had failed to show that its services benefited Nichols.…

In describing the elements of an action on an implied contract, the court of appeals stated in [Citation], that the party seeking recovery must show:

(1) the services were carried out under such circumstances as to give the recipient reason to understand:

(a) they were performed for him and not some other person, and

(b) they were not rendered gratuitously, but with the expectation of compensation from the recipient; and

(2) the services were beneficial to the recipient.

In applying the italicized language in [Citation] to the present controversy, it was the conclusion of the court of appeals that Roger’s’ services conferred no benefit on Nichols. We disagree. There was substantial evidence in the record to support a finding that, unless and until an effort was made to locate the subterranean sewer system, the city refused to allow the project to proceed. Consequently, it was necessary to the successful completion of the project that the effort be made. The fact that examination of the brick wall surrounding the underground creek indicated that it was unfeasible to use that source of drainage does not alter the fact that the project was stalemated until drainage into the underground creek was fully explored and rejected. The district court properly concluded that Roger’s’ services conferred a benefit on Nichols.…

Decision of court of appeals vacated; district court judgment affirmed.

Case questions

- What facts must be established by a plaintiff to show the existence of an implied contract?

- What argument did Nichols make as to why there was no implied contract here?

- How would the facts have to be changed to make an express contract?

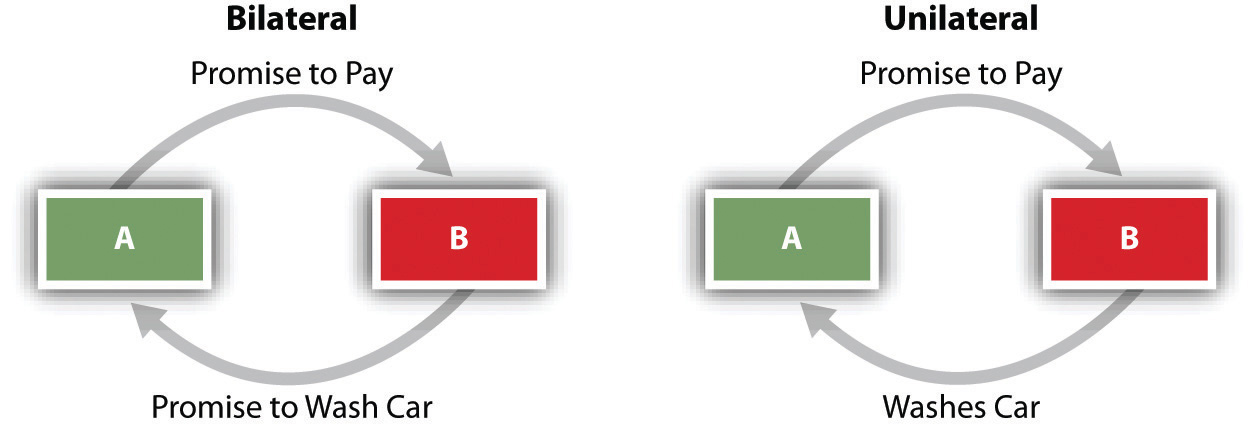

Bilateral or Unilateral Contracts

Bilateral Contracts

The typical contract is one in which both parties make mutual promises. Each is both promisor and promisee; that is, each pledges to do something, and each is the recipient of such a pledge. This type of contract is called a bilateral contract. The example above where the homeowner and the plumber enter a contract with express terms to fix the leaky fixture outside the house also illustrates a bilateral contract. The homeowner has offered payment, and the plumber has promised the repair.

Unilateral Contract

A unilateral contract is a contract where one party makes a promise and the other party can accept that promise only by performing a specific act. Unilateral contracts are as valid as bilateral contracts. Suppose that the homeowner puts a sign on their lawn that says “I will pay $100 to the first person to fix the leaky fixture outside my home.” A plumber sees the sign, says nothing, but goes to the pipe, gets to work, and repairs the leak. This is a unilateral contract. In a unilateral contract, the acceptance of the promise is indicated through performance, rather than by making a reciprocal promise.

Figure 5.2 Bilateral and Unilateral Contracts

Case 5.2

Woolley v. Hoffmann-La Roche, Inc., 491 A.2d 1257 (N.J. 1985)

WILNTZ, C. J.

Plaintiff, Richard Woolley, was hired by defendant, Hoffmann-La Roche, Inc., in October 1969, as an Engineering Section Head in defendant’s Central Engineering Department at Nutley. There was no written employment contract between plaintiff and defendant. Plaintiff began work in mid-November 1969. Sometime in December, plaintiff received and read the personnel manual on which his claims are based.

[The company’s personnel manual had eight pages;] five of the eight pages are devoted to “termination.” In addition to setting forth the purpose and policy of the termination section, it defines “the types of termination” as “layoff,” “discharge due to performance,” “discharge, disciplinary,” “retirement” and “resignation.” As one might expect, layoff is a termination caused by lack of work, retirement a termination caused by age, resignation a termination on the initiative of the employee, and discharge due to performance and discharge, disciplinary, are both terminations for cause. There is no category set forth for discharge without cause. The termination section includes “Guidelines for discharge due to performance,” consisting of a fairly detailed procedure to be used before an employee may be fired for cause. Preceding these definitions of the five categories of termination is a section on “Policy,” the first sentence of which provides: “It is the policy of Hoffmann-La Roche to retain to the extent consistent with company requirements, the services of all employees who perform their duties efficiently and effectively.”

In 1976, plaintiff was promoted, and in January 1977 he was promoted again, this latter time to Group Leader for the Civil Engineering, the Piping Design, the Plant Layout, and the Standards and Systems Sections. In March 1978, plaintiff was directed to write a report to his supervisors about piping problems in one of defendant’s buildings in Nutley. This report was written and submitted to plaintiff’s immediate supervisor on April 5, 1978. On May 3, 1978, stating that the General Manager of defendant’s Corporate Engineering Department had lost confidence in him, plaintiff’s supervisors requested his resignation. Following this, by letter dated May 22, 1978, plaintiff was formally asked for his resignation, to be effective July 15, 1978.

Plaintiff refused to resign. Two weeks later defendant again requested plaintiff’s resignation, and told him he would be fired if he did not resign. Plaintiff again declined, and he was fired in July.

Plaintiff filed a complaint alleging breach of contract.…The gist of plaintiff’s breach of contract claim is that the express and implied promises in defendant’s employment manual created a contract under which he could not be fired at will, but rather only for cause, and then only after the procedures outlined in the manual were followed. Plaintiff contends that he was not dismissed for good cause, and that his firing was a breach of contract.

Defendant’s motion for summary judgment was granted by the trial court, which held that the employment manual was not contractually binding on defendant, thus allowing defendant to terminate plaintiff’s employment at will. The Appellate Division affirmed. We granted certification.

The employer’s contention here is that the distribution of the manual was simply an expression of the company’s “philosophy” and therefore free of any possible contractual consequences. The former employee claims it could reasonably be read as an explicit statement of company policies intended to be followed by the company in the same manner as if they were expressed in an agreement signed by both employer and employees.…

This Court has long recognized the capacity of the common law to develop and adapt to current needs.…The interests of employees, employers, and the public lead to the conclusion that the common law of New Jersey should limit the right of an employer to fire an employee at will.

In order for an offer in the form of a promise to become enforceable, it must be accepted. Acceptance will depend on what the promisor bargained for: he may have bargained for a return promise that, if given, would result in a bilateral contract, both promises becoming enforceable. Or he may have bargained for some action or nonaction that, if given or withheld, would render his promise enforceable as a unilateral contract. In most of the cases involving an employer’s personnel policy manual, the document is prepared without any negotiations and is voluntarily distributed to the workforce by the employer. It seeks no return promise from the employees. It is reasonable to interpret it as seeking continued work from the employees, who, in most cases, are free to quit since they are almost always employees at will, not simply in the sense that the employer can fire them without cause, but in the sense that they can quit without breaching any obligation. Thus analyzed, the manual is an offer that seeks the formation of a unilateral contract—the employees’ bargained-for action needed to make the offer binding being their continued work when they have no obligation to continue.

The unilateral contract analysis is perfectly adequate for that employee who was aware of the manual and who continued to work intending that continuation to be the action in exchange for the employer’s promise; it is even more helpful in support of that conclusion if, but for the employer’s policy manual, the employee would have quit. See generally M. Petit, “Modern Unilateral Contracts,” 63 Boston Univ. Law Rev. 551 (1983) (judicial use of unilateral contract analysis in employment cases is widespread).

…All that this opinion requires of an employer is that it be fair. It would be unfair to allow an employer to distribute a policy manual that makes the workforce believe that certain promises have been made and then to allow the employer to renege on those promises. What is sought here is basic honesty: if the employer, for whatever reason, does not want the manual to be capable of being construed by the court as a binding contract, there are simple ways to attain that goal. All that need be done is the inclusion in a very prominent position of an appropriate statement that there is no promise of any kind by the employer contained in the manual; that regardless of what the manual says or provides, the employer promises nothing and remains free to change wages and all other working conditions without having to consult anyone and without anyone’s agreement; and that the employer continues to have the absolute power to fire anyone with or without good cause.

Reversed and remanded for trial.

Case questions

- What did Woolley do to show his acceptance of the terms of employment offered to him?

- In part of the case not included here, the court notes that Mr. Woolley died “before oral arguments on this case.” How can there be any damages if the plaintiff has died? Who now has any case to pursue?

- The court here is changing the law of employment in New Jersey. It is making case law, and the rule here articulated governs similar future cases in New Jersey. Why did the court make this change? Why is it relevant that the court says it would be easy for an employer to avoid this problem?

Valid, Void, Voidable and Unenforceable

Valid

A valid contract is a legally binding and enforceable agreement that meets all the essential elements required by contract law. If a contract contains all of the required elements and complies with all relevant laws and regulations, it is valid and enforceable. Parties to a valid contract have legal obligations to fulfill their promises.

Void

Not every agreement between two people is a binding contract. An agreement that is lacking one of the legal elements of a contract is a void contract — that is, not a contract at all. An agreement that is illegal—for example, a promise to commit a crime in return for a money payment—is void. Neither party to a void “contract” may enforce it.

Voidable

By contrast, a voidable contract is one that may become unenforceable by one party but can be enforced by the other. For example, a minor (any person under eighteen, in most states) may “avoid” a contract with an adult; the adult may not enforce the contract against the minor if the minor refuses to carry out the bargain. But the adult has no choice if the minor wishes the contract to be performed.

A voidable contract remains a valid contract until it is voided. Thus a contract with a minor remains in force unless the minor decides he or she does not wish to be bound by it. When the minor reaches majority, he or she may “ratify” the contract—that is, agree to be bound by it—in which case the contract will no longer be voidable and will thereafter be fully enforceable.

Unenforceable

An unenforceable contract is one that some rule of law bars a court from enforcing. For example, Tom owes Pete money, but Pete has waited too long to collect it and the statute of limitations has run out. The contract for repayment is unenforceable because he’s simply waited too long, and Pete is out of luck.

The Doctrine of Promissory Estoppel

A promise or what seems to be a promise is usually enforceable only if it is otherwise embedded in the elements necessary to make that promise a contract. Sometimes, though, people say things that seem like promises, and on which another person relies. In some circumstances courts have recognized that insisting on the existence of the traditional elements of contract to determine whether a promise is enforceable could work an injustice where there has been reliance. Thus developed the equitable doctrine of promissory estoppel, which has become an important adjunct to contract law. The Restatement (Section 90) puts it this way: “A promise which the promisor should reasonably expect to induce action or forbearance on the party of the promisee or a third person and which does induce such action or forbearance is binding if injustice can be avoided only by enforcement of the promise. The remedy granted for breach may be limited as justice requires.” To be “estopped” means to be prohibited from denying now the validity of a promise you made before. Contract protects agreements; promissory estoppel protects reliance, and that’s a significant difference. Practically speaking, promissory estoppel may serve to provide a remedy in situations where under traditional contract law, a party may have none.

Executory v. Executed

Executory and executed are terms used to describe the current status of a contract based on whether or not the parties have fulfilled their respective obligations at the moment of the classification. This helps us understand where the contract stands in terms of performance.

Executory

An executory contract is a contract in which one or more parties have not yet fulfilled their obligations or duties. In other words, the contractual promises made by one or more parties remain uncompleted or “in progress.” The completion of these promises is expected to occur in the future, and the contract is still active. Until all parties have performed their respective obligations, the contract remains executory. For example, if the homeowner has made an agreement with the plumber to come to their home to repair the leaky fixture, but the repair is not complete yet, the contract is executory.

Executed

An executed contract is a contract in which all parties involved have fully performed and completed their obligations. All promises made in the contract have been fulfilled, and there are no remaining duties or outstanding actions required. Once a contract is executed, it is considered closed, and the parties no longer have any legal obligations under that specific contract. The plumbing contract would be executed when the pipe leak is repaired, and the homeowner has paid the plumber for the service.

Formal and Informal Contracts

Formal contracts are contracts that require a specific form or format to be legally valid and enforceable. These formalities typically involve the manner in which the contract is created, executed, and documented. The four types of formal contracts recognized by the Restatement are (1) contracts under seal, (2) recognizances, (3) letters of credit, and (4) negotiable instruments.

The primary difference between a formal contract and an informal contract lies in the level of formality and the specific requirements for their creation and enforceability. Therefore, an informal contract is a contract that is not a formal contract. Note that this is not a difference between written and unwritten contracts. An informal contract can also be a written contract. The contract would be written and informal if there are no requirements that the contract be written in a specific format.

Activity 5A

Build a Contract

A contract may meet more than one of the classifications described in this chapter, but within certain categories, can only be classified in one way (for example, a contract can be formal OR informal, but not both). Use the drag and drop activity below to sample different combinations of contract classifications.

Additional Terminology: Suffixes Expressing Relationships

Although not really part of the classification of contracts, it is worth highlighting that in legal terminology, common English language suffixes (end syllables of words) are used to express relationships between parties. For example:

Offeror. One who makes an offer.

Offeree. One to whom an offer is made.

Promisor. One who makes a promise.

Promisee. One to whom a promise is made.

Obligor. One who makes and has an obligation.

Obligee. One to whom an obligation is made.

Transferor. One who makes a transfer.

Transferee. One to whom a transfer is made.

Check Your Understanding

a contract in which the terms and conditions are explicitly stated, either orally or in writing, with the intent of both parties to enter a contract

a contract in which the agreement is not explicitly stated in words but is inferred from the conduct and actions of the parties involved

quasi contract

an obligation imposed by a judge to prevent injustice and thus not a contract

one who makes a promise

one to whom a promise is made

a contract in which both parties exchange promises to perform

an agreement to pay in exchange for performance, if the potential performer chooses to act

a legally binding and enforceable agreement that meets all the essential elements required by contract law

agreeing verbally or in writing to the terms of a contract, which is one of the requirements to show there was a contract

an agreement that is lacking one or more of the legal elements of a contract

a contract that may become unenforceable by one party but can be enforced by the other

confirmation of an action which was not pre-approved and may not have been authorized

a contract that some rule of law bars a court from enforcing

a legal principle that prevents a person who made a promise from reneging when someone else has reasonably relied on the promise and will suffer a loss if the promise is broken

a contract in which one or more parties have not yet fulfilled their obligations or duties

a contract in which all parties involved have fully performed and completed their obligations

a contract that requires a specific form or format to be legally valid and enforceable

a contract that does not require consideration in order to be binding but that must be sealed, delivered, and show a clear intention of the parties to create a contract under seal

an obligation of record entered into before a court or magistrate requiring the performance of an act (such as appearance in court) usually under penalty of a money forfeiture

a letter addressed by a banker to a correspondent certifying that a person named therein is entitled to draw on the writer's credit up to a certain sum

a transferable instrument (as a note, check, or draft) containing an unconditional promise or order to pay to a holder or to the order of a holder upon issue, possession, demand, or at a specified time

any contract that is not a formal contract

one who makes an offer

a specific proposal to enter into an agreement with another; an offer is essential to the formation of an enforceable contract

one to whom an offer is made

one who makes and has an obligation

one to whom an obligation is made

one who makes a transfer

one to whom a transfer is made