Chapter 4 – Introduction to Tort Law

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

- Explain the purpose of tort law.

- Identify the three classifications of torts.

- Discuss various types of intentional torts.

- Explain negligence and defenses to claims of negligence.

- Describe strict liability torts and the reasons for them in the U.S. legal system.

In civil litigation, contract and tort claims are by far the most numerous. The law attempts to adjust for harms done by awarding damages to a successful plaintiff who demonstrates that the defendant was the cause of the plaintiff’s losses. This Chapter will explore the law of torts. Torts can be intentional torts, negligent torts, or strict liability torts. Employers must be aware that in many circumstances, the actions of their employees may create liability in tort. This Chapter explains the different kinds of torts, as well as available defenses to tort claims.

4.1 Purpose of Tort Laws

The term tort is the French equivalent of the English word wrong. The word tort is derived from the Latin word tortum, which means twisted or crooked or wrong. Long ago, tort was a word used in everyday speech; today it is left to the legal system. A judge will instruct a jury that a tort is usually defined as a wrong for which the law will provide a remedy, most often in the form of monetary damages. The law does not remedy all “wrongs.” Hurting someone’s feelings may be more devastating than saying something untrue about him behind his back; yet the law will not provide a remedy for saying something cruel to someone directly, while it may provide a remedy for "defaming" someone, orally or in writing, to others.

Although the word is no longer in general use, tort suits are the stuff of everyday headlines. More and more people injured by exposure to a variety of risks now seek redress (some sort of remedy through the courts). Headlines boast of multimillion-dollar jury awards against doctors who bungled operations, against newspapers that libeled subjects of stories, and against oil companies that devastate entire ecosystems. All are examples of tort suits.

The law of torts developed almost entirely in the common-law courts; that is, statutes passed by legislatures were not the source of law that plaintiffs usually relied on. Usually, plaintiffs would rely on the common law (judicial decisions). Through thousands of cases, the courts have fashioned a series of rules that govern the tortious conduct of individuals. Tort law holds individuals legally accountable for the consequences of their actions and those who suffer losses at the hands of others can be compensated.

Many acts (like murder) are both criminal and tortious. But torts and crimes are different. A crime is an act against the people as a whole. Society punishes the murderer; it does not usually compensate the family of the victim. Tort law, on the other hand, views the death as a private wrong for which damages are owed from the tortfeasor. In a civil case, the tort victim or his family, not the state, brings the action. The judgment against a defendant in a civil tort suit is usually expressed in monetary terms, not in terms of prison times or fines, and is the legal system’s way of trying to make up for the victim’s loss.

4.2 Types of Torts

There are three kinds of torts: intentional torts, negligent torts, and strict liability torts. Intentional torts arise from intentional acts, whereas unintentional torts often result from carelessness. Both intentional torts and negligent torts imply some fault on the part of the defendant. In strict liability torts, by contrast, there may be no fault at all, but tort law will sometimes require a defendant to make up for the victim’s losses even where the defendant was not careless and did not intend to do harm.

Dimensions of Tort Liability

There is a clear moral basis for recovery through the legal system where the defendant has been careless (negligent) or has intentionally caused harm. Using the concepts that we are free and autonomous beings with basic rights, we can see that when others interfere with either our freedom or our autonomy, we will usually react negatively. As the old saying goes, “Your right to swing your arm ends at the tip of my nose.” The law takes this even one step further: under intentional tort law, if you frighten someone by swinging your arms toward the tip of her nose, you may have committed the tort of assault, even if there is no actual touching (battery).

Under a capitalistic market system, rational economic rules also call for no negative externalities. That is, actions of individuals, either alone or in concert with others, should not negatively impact third parties. The law will try to compensate third parties who are harmed by your actions, even though it knows that a money judgment cannot actually mend a badly injured victim.

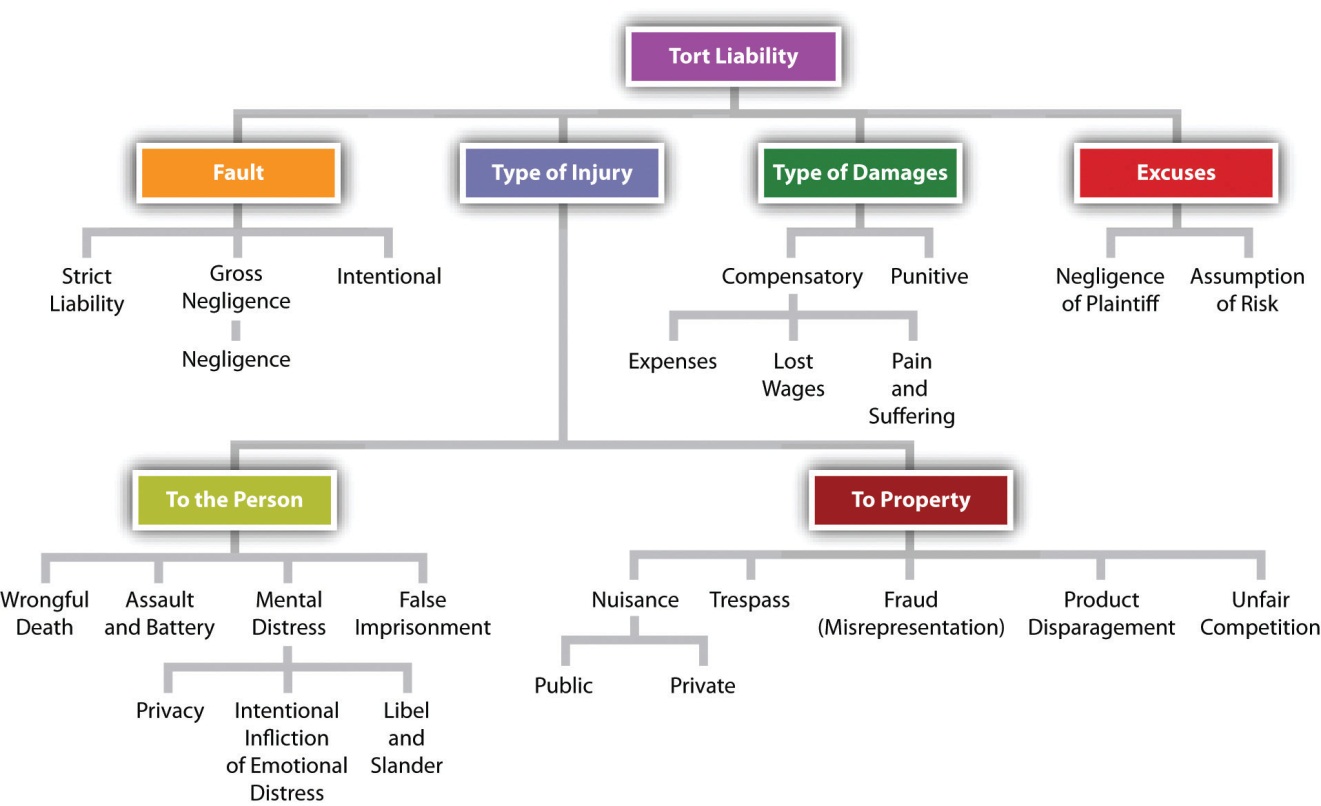

Figure 4.1 Dimensions of Tort Liability

Fault

Tort principles can be viewed along different dimensions. One is the fault dimension which requires a wrongful act by a defendant for the plaintiff to recover damages. The intent behind that act, however, need not be a specific intent. In other words, an innocent or relatively innocent action may still provide the basis for liability. Nevertheless, tort law—except for strict liability—relies on standards of fault, or blameworthiness.

The most obvious standard is willful conduct. If the defendant intentionally injures another, there is little argument about fault and tort liability. Thus, all crimes resulting in injury to a person or property (murder, assault, arson, etc.) are also torts, and the plaintiff may bring a civil lawsuit to recover damages for injuries to his person, family, or property.

Most tort suits do not rely on intentional fault. Most tort suits arise from negligent conduct that in the circumstances is careless or poses unreasonable risks of causing damage. Most automobile accident and medical malpractice suits are examples of negligence suits.

The fault dimension is a continuum. At one end of the continuum is the deliberate desire to do injury. The middle ground is occupied by careless conduct or negligence, and then at the other end of the continuum – no fault – is conduct that most would consider entirely blameless. In other words, the defendant may have observed all possible precautions and yet still be held liable. This is called strict liability. Here are examples illustrating the three different types of torts discussed in this section.

Sandy is at a shooting range practicing her marksmanship. Sandy gets into an argument with James. While yelling at James, Sandy points the gun toward him, and the gun discharges unexpectedly and a bullet strikes and injures James.

Sandy is at a shooting range practicing her marksmanship and showing James how to use her gun. James has not handled a gun before, and Sandy gives James the gun without making sure that the gun isn't loaded with live bullets. It turns out the gun is loaded, it discharges unexpectedly and a bullet strikes and injures James.

Sandy is at a shooting range practicing her marksmanship. The gun she uses is made by a manufacturer with a reputation for producing high-quality firearms. However, due to an unforeseen manufacturing defect in one batch of guns, a small number of them occasionally discharge unexpectedly. Sandy has unknowingly purchased one of those guns. Sandy is using reasonable safety precautions while using the gun, but without any warning the gun discharges unexpectedly injuring James.

Nature of Injury

Tort liability varies by the type of injury caused. The most obvious type of injury is physical harm to the person (assault, battery, infliction of emotional distress, negligent exposure to toxic pollutants, wrongful death). Mental suffering can be redressed if it is a result of physical injury (e.g., shock and depression following an automobile accident). A few states now permit recovery for mental distress without a physical injury (a mother’s shock at seeing her son injured by a car while both were crossing the street). Other protected interests include a person’s reputation (injured by defamatory statements or writings), a person’s privacy (injured by those who divulge secrets of his personal life), and a person’s economic interests (misrepresentation to secure an economic advantage, certain forms of unfair competition).

Other torts don’t result in harm to a person, but instead result in harm to their property (trespass, nuisance, interference with contract).

Damages

Since the purpose of tort law is to compensate the victim for harm actually done, damages are usually measured by the extent of the injury. Expressed in money terms, these include replacement of property destroyed, compensation for lost wages, reimbursement for medical expenses, and dollars that are supposed to approximate the pain that is suffered. Damages for these injuries are called compensatory damages.

In certain instances, the courts will permit an award of punitive damages. As the word punitive implies, the purpose is to punish the defendant’s actions. Because a punitive award (sometimes called exemplary damages) is at odds with the general purpose of tort law, it is allowable only in aggravated situations. The law in most states permits recovery of punitive damages only when the defendant has deliberately committed a wrong with malicious intent or has otherwise done something outrageous.

Punitive damages are rarely allowed in negligence cases for that reason. But if someone sets out intentionally and maliciously to hurt another person, punitive damages may well be appropriate. Punitive damages are intended not only to punish the wrongdoer, by exacting an additional and sometimes heavy payment (the exact amount is left to the discretion of jury and judge), but also to deter others from similar conduct. The punitive damage award has been subject to heavy criticism in recent years in cases in which it has been awarded against manufacturers. One fear is that huge damage awards on behalf of a multitude of victims could swiftly bankrupt the defendant. Unlike compensatory damages, punitive damages are taxable.

Excuses

The law does not condemn every act that ultimately results in injury. Excuses are recognized under certain circumstances when the defendant's actions, although they might have caused harm, are considered justified or excusable due to specific reasons.

One common rule of exculpation is assumption of risk. A baseball fan who sits along the third base line close to the infield assumes the risk that a line drive foul ball may fly toward him and strike him. He will not be permitted to complain in court that the batter should have been more careful or that management should have either warned him or put up a protective barrier.

Another excuse is negligence of the plaintiff. If two drivers are careless and hit each other on the highway, some states will refuse to permit either to recover from the other. Still another excuse is consent: two boxers in the ring consent to being struck with fists (but not to being bitten on the ear).

4.3 Intentional Torts

Keeping these dimensions of torts in mind, let’s turn to a discussion of intentional torts. There are several intentional torts, and some common ones are illustrated in this section.

Assault and Battery

One of the most obvious intentional torts is assault and battery as tort law seeks to restrain individuals from using physical force on others. Assault is (1) the threat of immediate harm or offense of contact or (2) any act that would arouse reasonable apprehension of imminent harm. Battery is unauthorized and harmful or offensive physical contact with another person that causes injury. At common law, these were two separate torts. Some states now merge these torts and treat them together as a single tort.

Often an assault results in battery, but not always. Consider these three examples:

Alex is walking down the street when they suddenly become angry with Taylor. Alex clenches their fist and shouts at Taylor, "I'm going to punch you!" This is an assault as this could create a reasonable apprehension in Taylor's mind that imminent harmful physical contact is about to occur.

Alex is walking down the street when they suddenly become angry with Taylor. Alex runs up to Taylor from behind and punches Taylor in the back. This is a battery. This physical contact is an intentional act which (without consent or justification) caused harm.

Alex is walking down the street when they suddenly become angry with Taylor. Alex clenches their fist and shouts at Taylor, "I'm going to punch you!" Alex runs up and punches Taylor. Both assault and battery are present in this situation. The initial threat created the apprehension of imminent harm, and their subsequent physical act of the punch fulfilled that threat.

Transferred intent allows for the intent behind an action to be transferred from the intended victim to the actual victim. For example, If Alex becomes angry at Taylor and runs up to Taylor intending to land a punch, but Alex mistakenly punches Hermione, this is still an intentional tort. The intent to touch in an offensive way (battery) would transfer from Alex to Hermione, thus Hermione could sue Alex for battery for any damages she had suffered.

False Imprisonment

The tort of false imprisonment originally implied a locking up, as in a prison, but today it can occur if a person is restrained in a room or a car or even if his or her movements are restricted while walking down the street. People have a right to be free to go as they please, and anyone who, without cause, deprives another of that personal freedom has committed a tort. The intent requirement in the context of false imprisonment refers to the defendant's state of mind when engaging in the actions that led to the confinement. Specifically, the plaintiff needs to show that the defendant intended to confine or restrain them against their will. However, it's important to understand that the intent requirement does not necessarily mean that the defendant must have intended to cause harm to the plaintiff or to commit false imprisonment. The key aspect is the defendant's intent to confine the plaintiff, and the loss of liberty to the Plaintiff is enough to show harm.

Damages are allowed for time lost, discomfort and resulting ill health, mental suffering, humiliation, and loss of reputation or business.

Case 4.1

Lester v. Albers Super Markets, Inc., 94 Ohio App. 313, 114 N.E.2d 529 (Ohio 1952)

Facts: The plaintiff, carrying a bag of rolls purchased at another store, entered the defendant’s grocery store to buy some canned fruit. Seeing her bus outside, she stepped out of line and put the can on the counter. The store manager intercepted her and repeatedly demanded that she submit the bag to be searched. Finally, she acquiesced; he looked inside and said she could go. She testified that several people witnessed the scene, which lasted about fifteen minutes, and that she was humiliated. The jury awarded her $800. She also testified that no one laid a hand on her or made a move to restrain her from leaving by any one of numerous exits.

* * *

MATTHEWS, JUDGE.

As we view the record, it raises the fundamental question of what is imprisonment. Before any need for a determination of illegality arises there must be proof of imprisonment. In 35 Corpus Juris Secundum (C.J.S.), False Imprisonment, § II, pages 512–13, it is said: “Submission to the mere verbal direction of another, unaccompanied by force or by threats of any character, cannot constitute a false imprisonment, and there is no false imprisonment where an employer interviewing an employee declines to terminate the interview if no force or threat of force is used and false imprisonment may not be predicated on a person’s unfounded belief that he was restrained.”

Many cases are cited in support of the text.

* * *

In Fenn v. Kroger Grocery & Baking Co., Mo. Sup., 209 S.W. 885, 887, the court said:

A case was not made out for false arrest. The plaintiff said she was intercepted as she started to leave the store; that Mr. Krause stood where she could not pass him in going out. She does not say that he made any attempt to intercept her. She says he escorted her back to the desk, that he asked her to let him see the change.

…She does not say that she went unwillingly…Evidence is wholly lacking to show that she was detained by force or threats. It was probably a disagreeable experience, a humiliating one to her, but she came out victorious and was allowed to go when she desired with the assurance of Mr. Krause that it was all right. The demurrer to the evidence on both counts was properly sustained.

The result of the cases is epitomized in 22 Am.Jur. 368, as follows:

A customer or patron who apparently has not paid for what he has received may be detained for a reasonable time to investigate the circumstances, but upon payment of the demand, he has the unqualified right to leave the premises without restraint, so far as the proprietor is concerned, and it is false imprisonment for a private individual to detain one for an unreasonable time, or under unreasonable circumstances, for the purpose of investigating a dispute over the payment of a bill alleged to be owed by the person detained for cash services.

* * *

For these reasons, the judgment is reversed and final judgment entered for the defendant-appellant.

Case questions

- The court begins by saying what false imprisonment is not. What is the legal definition of false imprisonment?

- What kinds of detention are permissible for a store to use in accosting those that may have been shoplifting?

- Jody broke up with Jeremy and refused to talk to him. Jeremy saw Jody get into her car near the business school and parked right behind her so she could not move. He then stood next to the driver’s window for fifteen minutes, begging Jody to talk to him. She kept saying, “No, let me leave!” Has Jeremy committed the tort of false imprisonment?

Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress

The tort of intentional infliction of emotional distress (IIED) is a legal claim that allows individuals to seek compensation for severe emotional distress or mental anguish caused by the intentional and outrageous conduct of another party. Like other intentional torts, the defendant's actions must be intentional. The conduct of the defendant must involve extreme and outrageous behavior that goes beyond the bounds of decency. The plaintiff must suffer severe emotional distress as a result of the defendant's actions. Proving an IIED claims can be challenging as the threshold for establishing extreme and outrageous conduct is a high one. Examples of conduct that might lead to a successful IIED claim include intentional acts such as deliberate humiliation, intentional infliction of fear, or intentional spreading of false and harmful rumors. Many states require that this distress must result in physical symptoms such as nausea, headaches, ulcers, or, as in the case of the pregnant wife, a miscarriage. Other states have not required physical symptoms, finding that shame, embarrassment, fear, and anger constitute severe mental distress.

In an early California case, bill collectors came to the debtor’s home repeatedly and threatened the debtor’s pregnant wife. Among other things, they claimed that the wife would have to deliver her child in prison. The wife miscarried and had emotional and physical complications. The court found that the behavior of the collection company’s two agents was sufficiently outrageous to prove the tort of intentional infliction of emotional distress

Trespass and Nuisance

Trespass is intentionally going on land that belongs to someone else or putting something on someone else’s property and refusing to remove it. This part of tort law shows how strongly the law values the rights of property owners. The right to enjoy your property without interference from others is also found in common law of nuisance. To illustrate the difference between trespass and nuisance, consider this scenario. Roberto owns a piece of land, and Ysabel, without Roberto's permission, regularly enters his property to access a shortcut to a nearby park. In this scenario, Ysabel's repeated unauthorized entry onto Roberto's property constitutes a trespass. Trespass occurs when someone intentionally enters another person's property without permission. Even if Ysabel is just using the shortcut and doesn't cause any damage, the act of entering the property without authorization constitutes a trespass. Over time, Ysabel's continuous use of the shortcut and the resulting annoyance and inconvenience to Roberto and his neighbors can be considered a nuisance. Nuisance involves the unreasonable interference with another person's use and enjoyment of their property. Trespass focuses on the physical presence on the property without permission, while nuisance focuses on the unreasonable interference with the enjoyment of the property.

There are limits to property owners’ rights, however. In the case of Katko v. Briney, a property owner set up a spring gun in an abandoned farmhouse on his property. The gun was rigged in such a way that if an intruder entered the farmhouse unlawfully, the gun would discharge and potentially cause harm. When an intruder entered the farmhouse, it triggered the spring gun to discharge, severely injuring him. He sued the property owner claiming that the use of the spring gun constituted an unreasonable use of force. The Court found that the use of a spring gun in a potentially lethal way was unreasonable as an intruder to an abandoned house posed no threat to human life.

The rigging of a spring gun is an intentional act, but in the case of negligence on the part of the landowner, states have differing rules about trespass and negligence. In some states, a trespasser is only protected against the gross negligence of the landowner. In other states, trespassers may be owed the duty of due care on the part of the landowner. For example, consider if a very small child wanders off his own property and falls into a gravel pit on a nearby property; if the pit should (in the exercise of due care) have been filled in or some barrier erected around it, then there was negligence. But if the state law holds that the duty to trespassers is only to avoid gross negligence, the child’s family would lose, unless the state law makes an exception for very young trespassers. In general, guests, licensees, and invitees are owed a duty of due care; a trespasser may not be owed such a duty, but states have different rules on this.

Intentional Interference with Contractual Relations

The tort of intentional interference with contractual relations involves a situation where a third party intentionally takes actions to disrupt or interfere with an existing contractual relationship between two parties, causing harm to one of the parties involved. This tort can generally be established by proving four elements:

- There was a contract between the plaintiff and a third party.

- The defendant knew of the contract.

- The defendant improperly induced the third party to breach the contract or made performance of the contract impossible.

- There was injury to the plaintiff.

In a famous case of interference with contract relations, Texaco was sued by Pennzoil for interfering with an agreement that Pennzoil had with Getty Oil. After complicated negotiations between Pennzoil and Getty, a takeover share price was struck, a memorandum of understanding was signed, and a press release announced an agreement in principle between Pennzoil and Getty. Texaco’s lawyers, however, believed that Getty Oil was “still in play,” and before the lawyers for Pennzoil and Getty could complete the paperwork for their agreement, Texaco announced it was offering Getty shareholders an additional $12.50 per share over what Pennzoil had offered.

Texaco later increased its offer to $228 per share, and the Getty board of directors soon began dealing with Texaco instead of Pennzoil. Pennzoil decided to sue in Texas state court for tortious interference with a contract. After a long trial, the jury returned an enormous verdict against Texaco: $7.53 billion in actual damages and $3 billion in punitive damages. The verdict was so large that it would have bankrupted Texaco. After appeals were filed, Texaco agreed to pay $3 billion to Pennzoil to dismiss its claim of tortious interference with a contract.

Activity 4A

Case Debate:

Should punitive damages be available in intentional interference with contractual relations cases?

A breach of contract occurs when one party to a contract fails to fulfill its obligations as outlined in a valid and enforceable contract. As you will learn later in the course, punitive damages are generally not available in contract lawsuits. Yet, as noted in the Texaco case above, punitive damages, and a lot of them, were awarded in the tort case centered on interference with a contract.

Question: What makes a breach of contract case different than an intentional interference with contract case?

Question: In what way is a breach of contract case similar to a case that is centered on intentional interference with contract?

Case Debate: Look up a credible internet resource discussing punitive damages in tort actions. Should an interference with contract case be eligible for punitive damages against a third-party tortfeasor, when the party that actually decided to breach the contract would only be liable for compensatory damages?

Misuse of the Legal System

Malicious prosecution, abuse of process, and wrongful use of civil proceedings are all torts that involve misuse or abuse of the legal system. Here's a brief explanation of each:

Malicious Prosecution

Malicious prosecution is a tort causing someone to be prosecuted for a criminal act, knowing that there was no probable cause to believe that the plaintiff committed the crime. To be clear, the Plaintiff in the tort case would have been the Defendant accused of, but did not commit, a criminal act. Key to this tort is there must be a lack of reasonable grounds to initiate a criminal legal action, and malice in so initiating that action. The criminal proceeding must terminate in the plaintiff’s favor in order for his suit to be sustained. As with all torts, there must be a legal injury.

Wrongful Use of Civil Proceedings

Wrongful use of civil proceedings is similar to malicious prosecution but applies to civil cases. It involves the initiation of a civil lawsuit without proper grounds or with an improper motive, resulting in harm to the defendant. Civil litigation is usually costly and burdensome, and one who forces another to defend himself against baseless accusations should not be permitted to saddle the one he sues with the costs of defense. Like malicious prosecution, this tort provides a remedy for those who have been wrongfully sued in civil court. However, because, as a matter of public policy, litigation is favored as the means by which legal rights can be vindicated—indeed, the Supreme Court has even ruled that individuals have a constitutional right to litigate—the plaintiff must meet a heavy burden in proving his case.

Abuse of Process

Abuse of process is another legal tort related to the misuse of legal proceedings. It involves using a legal process itself to achieve some ulterior motive, such as intimidation or gaining an unfair advantage. In malicious prosecution and in wrongful use of civil proceedings, someone falsely accuses another person and starts a lawsuit without any real reason. In abuse of process differs because it focuses more narrowly on a legal process. So, there could be a real case for the Courts, but a litigant might be using a legal procedure within that case in a tricky or unfair way.

Defamation

Defamation involves making a false statement that causes injury to a person’s good name or reputation. The Restatement (Second) of Torts defines a defamatory communication as one that “so tends to harm the reputation of another as to lower him in the estimation of the community or to deter third persons from associating or dealing with him.”

In general, if the harm is done through the spoken word—one person to another, by telephone, by radio, or on television—it is called slander. If the defamatory statement is published in written form, it is called libel.

A statement is not defamatory unless it is false. Truth is an absolute defense to a charge of libel or slander. Moreover, the statement must be “published”—that is, communicated to a third person. You cannot be libeled by one who sends you a letter full of false accusations and scurrilous statements about you unless a third person opens it first (your roommate, perhaps). Any living person is capable of being defamed, but the dead are not. Corporations, partnerships, and other forms of associations can also be defamed if the statements tend to injure their ability to do business or to garner contributions.

The statement must have reference to a particular person, but he or she need not be identified by name. A statement that “the company president is a crook” is defamatory, as is a statement that “the major network weathermen are imposters.” The company president and the network weathermen could show that the words were aimed at them. But statements about large groups will not support an action for defamation (e.g., “all doctors are butchers” is not defamatory of any particular doctor). Publishing false information about another business’s product constitutes the tort of slander of quality, or trade libel. In some states, this is known as the tort of product disparagement. It may be difficult to establish damages, however. A plaintiff must prove that actual damages proximately resulted from the slander of quality and must also show the extent of the economic harm.

That a person did not intend to defame is not an excuse; a typographical error that converts a true statement into a false one in a newspaper, magazine, or corporate brochure can be sufficient to make a case of libel. Even the exercise of due care is usually no excuse if the statement is in fact communicated. Repeating a libel is itself a libel; a libel cannot be justified by showing that you were quoting someone else.

On the other hand, even if a plaintiff is able to prove that a defamatory statement was made, and a harm to reputation resulted, he is not necessarily entitled to an award of damages. That is because the law contains a number of privileges that excuse the defamation.

Absolute Privilege

Statements made during the course of judicial proceedings are absolutely privileged, meaning that they cannot serve as the basis for a defamation suit. Accurate accounts of judicial or other proceedings are absolutely privileged; a newspaper, for example, may pass on the slanderous comments of a judge in court. “Judicial” is broadly construed to include most proceedings of administrative bodies of the government. The Constitution exempts members of Congress from suits for libel or slander for any statements made in connection with legislative business. The courts have constructed a similar privilege for many executive branch officials.

Qualified Privilege

Absolute privileges pertain to those in the public sector. A narrower privilege exists for private citizens. In general, a statement that would otherwise be actionable is held to be justified if made in a reasonable manner and for a reasonable purpose. Thus, you may warn a friend to beware of dealing with a third person, and if you had reason to believe that what you said was true, you are privileged to issue the warning, even though false. Likewise, an employee may warn an employer about the conduct or character of a fellow or prospective employee, and a parent may complain to a school board about the competence or conduct of a child’s teacher. There is a line to be drawn, however, and a defendant with nothing but an idle interest in the matter (an “officious intermeddler”) must take the risk that his information is wrong.

In 1964, the Supreme Court handed down its historic decision in New York Times v. Sullivan, holding that under the First Amendment a libel judgment brought by a public official against a newspaper cannot stand unless the plaintiff has shown “actual malice,” which in turn was defined as “knowledge that [the statement] was false or with a reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.” In subsequent cases, the court extended the constitutional doctrine further, applying it not merely to government officials but to public figures, people who voluntarily place themselves in the public eye or who involuntarily find themselves the objects of public scrutiny. Whether a private person is or is not a public figure is a difficult question that has so far eluded rigorous definition and has been answered only from case to case. A CEO of a private corporation ordinarily would be considered a private figure unless he puts himself in the public eye—for example, by starring in the company’s television commercials.

Invasion of Privacy

Invasion of privacy involves violating an individual's right to keep certain aspects of their personal life private – it is a right “to be let alone.” This tort encompasses a range of situations where someone's privacy is intruded upon without their consent, leading to emotional distress, embarrassment, or other negative consequences. Courts and commentators have discerned at least four different types of interests: (1) the right to control the appropriation of your name and picture for commercial purposes, (2) the right to be free of intrusion on your “personal space” or seclusion, (3) freedom from public disclosure of embarrassing and intimate facts of your personal life, and (4) the right not to be presented in a “false light.”

Appropriation of Name or Likeness

This happens when someone uses an individual's name, likeness, or identity for commercial purposes without their permission, such as using someone's photo in an advertisement without their consent. This is the earliest privacy interest recognized by the courts. The aggrieved person can sue and recover damages for use of their likeness including unauthorized profits and also to have the court enjoin (judicially block) any further unauthorized use of the plaintiff’s name, likeness, or image.

Personal Space

This occurs when someone intentionally intrudes upon an individual's private space or personal affairs without a legitimate reason. Developed and extended over time, today, for example, taking photos of someone else with your cell phone in a locker room could constitute invasion of the right to privacy. Reading someone else’s mail or e-mail could also constitute an invasion of the right to privacy. Photographing someone on a city street is not tortious, but subsequent use of the photograph could be. Whether the invasion is in a public or private space, the amount of damages will depend on how the image or information is disclosed to others.

Public Disclosure of Embarrassing Facts

This involves revealing private and sensitive information about an individual to the public without their consent, causing harm or embarrassment. While circulation of false statements that do injury to a person are actionable under the laws of defamation, public disclosure protects the invasion of privacy into true statements when they are private and of no legitimate concern to the public. This might include publishing personal medical records, private conversations, or other intimate information, but may not extend as broadly to those that live life in the public eye.

False Light

False light occurs when false information is presented about an individual that portrays them inaccurately and in a false light, leading to harm or emotional distress. Though false, this might not be the same as defamation as the information presented may not be libelous or harm an individual’s reputation. Indeed, the publication might even glorify the plaintiff, making them seem more heroic than they actually are. Subject to the First Amendment requirement that the plaintiff must show intent or extreme recklessness, statements that put a person in a false light, like a fictionalized biography, are actionable.

4.4 Negligence

Elements of Negligence

Negligence occurs when someone doesn't take the proper level of care that a reasonably prudent person would in a similar situation, and this failure leads to harm. In layman's terms, this describes an accident. The law imposes a duty of care on all of us in our everyday lives and accidents caused by negligence are actionable. Negligence is not an intentional tort because in negligence there is no intent to harm another person or thing, but the resulting harm occurs because of a lack of reasonable care. The tort of negligence has four elements: (1) a duty of due care that the defendant had, (2) the breach of the duty of due care, (3) connection between cause and injury, and (4) actual damage or loss. Even if a plaintiff can prove each of these aspects, the defendant may be able to show that the law excuses the conduct that is the basis for the tort claim. We examine each of these factors below.

Standard of Care

Not every unintentional act that causes injury is negligent. If you brake to a stop when you see a child dart out in front of your car, and if the noise from your tires gives someone in a nearby house a heart attack, you have not acted negligently toward the person in the house. The purpose of the negligence standard is to protect others against the risk of injury that foreseeably would ensue from unreasonably dangerous conduct.

The law has tried to encapsulate this idea in the form of the famous standard of “the reasonable person.” This fictitious person “of ordinary prudence” is the model that juries are instructed to compare defendants with in assessing whether those defendants have acted negligently. If a defendant has acted “unreasonably under the circumstances” and his conduct posed an unreasonable risk of injury, then he is liable for injury caused by his conduct. Perhaps in most instances, it is not difficult to divine what the reasonable man would do. The reasonable man stops for traffic lights and always drives at reasonable speeds, does not throw baseballs through windows, performs surgical operations according to the average standards of the medical profession, ensures that the floors of his grocery store are kept free of fluids that would cause a patron to slip and fall, takes proper precautions to avoid spillage of oil from his supertanker, and so on. The "reasonable man" standard imposes hindsight on the decisions and actions of people in society; however, the circumstances of life are such that courts may sometimes impose a standard of due care that many people might not find reasonable.

Duty of Care

Duty of care refers to the legal obligation or responsibility that an individual owes to others to act in a way that does not put them at an unreasonable risk of harm. In a negligence claim, the plaintiff must show that the defendant had a duty of care toward them. This means that the defendant should have acted in a way that a reasonably prudent person would have in similar circumstances.

The law does not impose on us a duty to care for every person. In general, the law imposes no obligation to act in a situation to which we are strangers. We may pass by the drowning child without risking a lawsuit. But if we do act, then the law requires us to act carefully. The law of negligence requires us to behave with due regard for the foreseeable consequences of our actions in order to avoid unreasonable risks of injury. Affirmatively determining a duty of care can be difficult. Physicians, for example, are bound by principles of medical ethics to respect the confidences of their patients, which would place a heightened duty of care on them in their medical capacity, but not necessarily as individuals. In some situations, it may be difficult to tell in what capacity a person with medical expertise is acting.

Case 4.2

Whitlock v. University of Denver, 744 P.2d 54 (Supreme Court of Colorado 1987)

Factual Summary: On June 19, 1978, at approximately 10:00 p.m., plaintiff Oscar Whitlock suffered a paralyzing injury while attempting to complete a one-and-three-quarters front flip on a trampoline. As Whitlock attempted to perform the one-and-three-quarters front flip, he landed on the back of his head, causing his neck to break. The injury rendered him a quadriplegic. The trampoline was owned by the Beta Theta Pi fraternity (the Beta house) and was situated on the front yard of the fraternity premises, located on the University campus. At the time of his injury, Whitlock was twenty years old, attended the University of Denver, and was a member of the Beta house, where he held the office of acting house manager. The property on which the Beta house was located was leased to the local chapter house association of the Beta Theta Pi fraternity by the defendant University of Denver.

Whitlock had extensive experience jumping on trampolines and at trial recounted prior to his accident he had successfully executed the one-and-three-quarters front flip between seventy-five and one hundred times on the Beta house trampoline.

Whitlock brought suit against the manufacturer and seller of the trampoline, the University, the Beta Theta Pi fraternity and its local chapter, reaching settlements with all Defendants except the University.

At trial, the jury returned a verdict in favor of Whitlock, assessing his total damages at $ 7,300,000. The jury attributed twenty-eight percent of causal negligence to the conduct of Whitlock and seventy-two percent of causal negligence to the conduct of the University. The trial court accordingly reduced the amount of the award against the University to $ 5,256,000. On appeal, the court of appeals held that the University owed Whitlock a duty of due care to remove the trampoline from the fraternity premises or to supervise its use. The University then appealed to the state Supreme Court.

JUSTICE LOHR delivered the Opinion of the Court.

II.

A negligence claim must fail if based on circumstances for which the law imposes no duty of care upon the defendant for the benefit of the plaintiff. …

Whether the law should impose a duty requires consideration of many factors including, for example, the risk involved, the foreseeability and likelihood of injury as weighed against the social utility of the actor’s conduct, the magnitude of the burden of guarding against injury or harm, and the consequences of placing the burden upon the actor.

…

We believe that the fact that the University is charged with negligent failure to act rather than negligent affirmative action is a critical factor that strongly militates against imposition of a duty on the University under the facts of this case. In determining whether a defendant owes a duty to a particular plaintiff, the law has long recognized a distinction between action and a failure to act. …

The fact that an actor realizes or should realize that action on his part is necessary for another’s aid or protection does not of itself impose upon him a duty to take such action.

Imposition of a duty in all such cases would simply not meet the test of fairness under contemporary standards.

…

III.

The present case involves the alleged negligent failure to act, rather than negligent action. The plaintiff does not complain of any affirmative action taken by the University, but asserts instead that the University owed to Whitlock the duty to assure that the fraternity’s trampoline was used only under supervised conditions comparable to those in a gymnasium class, or in the alternative to cause the trampoline to be removed from the front lawn of the Beta house.…

A.

The student-university relationship has been scrutinized in several jurisdictions, and it is generally agreed that a university is not an insurer of its students’ safety. [Citations]

…By imposing a duty on the University in this case, the University would be encouraged to exercise more control over private student recreational choices, thereby effectively taking away much of the responsibility recently recognized in students for making their own decisions with respect to private entertainment and personal safety. …

…

Aside from advising the Beta house on one occasion to put the trampoline up when not in use, there is no evidence that the University officials attempted to assert control over trampoline use by the fraternity members. We conclude from this record that the University’s very limited actions concerning safety of student recreation did not give Whitlock or the other members of campus fraternities or sororities any reason to depend upon the University for evaluation of the safety of trampoline use.…Therefore, we conclude that the student-university relationship is not a special relationship of the type giving rise to a duty of the University to take reasonable measures to protect the members of fraternities and sororities from risks of engaging in extra-curricular trampoline jumping….

We [also] conclude that the relationship between the University and Whitlock was not one of dependence with respect to the activities at issue here, and provides no basis for the recognition of a duty of the University to take measures for protection of Whitlock against the injury that he suffered.

…

IV.

Considering all of the factors presented, we are persuaded that under the facts of this case the University of Denver had no duty to Whitlock to eliminate the private use of trampolines on its campus or to supervise that use. There exists no special relationship between the parties that justifies placing a duty upon the University to protect Whitlock from the well-known dangers of using a trampoline. Here, a conclusion that a special relationship existed between Whitlock and the University sufficient to warrant the imposition of liability for nonfeasance would directly contravene the competing social policy of fostering an educational environment of student autonomy and independence.

We reverse the judgment of the court of appeals and return this case to that court with directions to remand it to the trial court for dismissal of Whitlock’s complaint against the University.

Case questions

- How are comparative negligence numbers calculated by the trial court? How can the jury say that the University is 72 percent negligent and that Whitlock is 28 percent negligent?

- Why is this not an assumption of risk case?

- Is there any evidence that Whitlock was contributorily negligent? If not, why would the court engage in comparative negligence calculations?

Breach of Duty of Care

Breach of duty of care occurs when the defendant fails to meet the standard of care that a reasonably prudent person would have exercised in similar circumstances. A plaintiff must demonstrate that the defendant's actions (or inactions) fell below the expected standard of care, indicating negligence. Essentially, the defendant's behavior did not meet the level of care that a reasonable person would have taken.

Establishing a breach of the duty of due care where the defendant has violated a statute or municipal ordinance is eased considerably with the doctrine of negligence per se, a doctrine common to all U.S. state courts. If a legislative body sets a minimum standard of care for particular kinds of acts to protect a certain set of people from harm and a violation of that standard causes harm to someone in that set, the defendant is negligent per se. For example, If Harvey is driving sixty-five miles per hour in a fifty-five-mile-per-hour zone when he crashes into Haley’s car and the police accident report establishes that or he otherwise admits to going ten miles per hour over the speed limit, Haley does not have to prove that Harvey has breached a duty of due care. She will only have to prove that the speeding was an actual and proximate cause of the collision and will also have to prove the extent of the resulting damages to her.

Causation: Actual Cause and Proximate Cause

Causation involves establishing a direct link between the defendant's breach of duty and the harm suffered by the plaintiff. In tort theory, there are two kinds of causes that a plaintiff must prove: actual cause and proximate cause. Actual cause (causation in fact) can be found if the connection between the defendant’s act and the plaintiff’s injuries passes the “but for” test: if an injury would not have occurred “but for” the defendant’s conduct, then the defendant is the cause of the injury. Still, this is not enough causation to create liability. The injuries to the plaintiff must also be foreseeable, or not “too remote,” for the defendant’s act to create liability. This is proximate cause: a cause that is not too remote or unforeseeable. For proximate cause, foreseeability is key. The harm suffered by the plaintiff must have been a foreseeable consequence of the defendant's breach of duty.

Case 4.3

Palsgraf v. Long Island R.R., 248 N.Y. 339,162 N.E. 99 (N.Y. 1928)

CARDOZO, C. J.

Plaintiff was standing on a platform of defendant’s railroad after buying a ticket to go to Rockaway Beach. A train stopped at the station, bound for another place. Two men ran forward to catch it. One of the men reached the platform of the car without mishap, though the train was already moving. The other man, carrying a package, jumped aboard the car, but seemed unsteady as if about to fall. A guard on the car, who had held the door open, reached forward to help him in, and another guard on the platform pushed him from behind. In this act, the package was dislodged, and fell upon the rails. It was a package of small size, about fifteen inches long, and was covered by a newspaper. In fact it contained fireworks, but there was nothing in its appearance to give notice of its contents. The fireworks when they fell exploded. The shock of· the explosion threw down some scales at the other end of the platform many feet away. The scales struck the plaintiff, causing injuries for which she sues.

The conduct of the defendant’s guard, if a wrong in its relation to the holder of the package, was not a wrong in its relation to the plaintiff, standing far away. Relatively to her it was not negligence at all. Nothing in the situation gave notice that the falling package had in it the potency of peril to persons thus removed. Negligence is not actionable unless it involves the invasion of a legally protected interest, the violation of a right. “Proof of negligence in the air, so to speak, will not do.…If no hazard was apparent to the eye of ordinary vigilance, an act innocent and harmless, at least to outward seeming, with reference to her, did not take to itself the quality of a tort because it happened to be a wrong, though apparently not one involving the risk of bodily insecurity, with reference to someone else.…The plaintiff sues in her own right for a wrong personal to her, and not as the vicarious beneficiary of a breach of duty to another.

A different conclusion will involve us, and swiftly too, in a maze of contradictions. A guard stumbles over a package which has been left upon a platform.

It seems to be a bundle of newspapers. It turns out to be a can of dynamite. To the eye of ordinary vigilance, the bundle is abandoned waste, which may be kicked or trod on with impunity. Is a passenger at the other end of the platform protected by the law against the unsuspected hazard concealed beneath the waste? If not, is the result to be any different, so far as the distant passenger is concerned, when the guard stumbles over a valise which a truckman or a porter has left upon the walk?…The orbit of the danger as disclosed to the eye of reasonable vigilance would be the orbit of the duty. One who jostles one’s neighbor in a crowd does not invade the rights of others standing at the outer fringe when the unintended contact casts a bomb upon the ground. The wrongdoer as to them is the man who carries the bomb, not the one who explodes it without suspicion of the danger. Life will have to be made over, and human nature transformed, before prevision so extravagant can be accepted as the norm of conduct, the customary standard to which behavior must conform.

The argument for the plaintiff is built upon the shifting meanings of such words as “wrong” and “wrongful” and shares their instability. For what the plaintiff must show is a “wrong” to herself; i.e., a violation of her own right, and not merely a “wrong” to someone else, nor conduct “wrongful” because unsocial, but not a “wrong” to anyone. We are told that one who drives at reckless speed through a crowded city street is guilty of a negligent act and therefore of a wrongful one, irrespective of the consequences.

Negligent the act is, and wrongful in the sense that it is unsocial, but wrongful and unsocial in relation to other travelers, only because the eye of vigilance perceives the risk of damage. If the same act were to be committed on a speedway or a race course, it would lose its wrongful quality. The risk reasonably to be perceived defines the duty to be obeyed, and risk imports relation; it is risk to another or to others within the range of apprehension. This does not mean, of course, that one who launches a destructive force is always relieved of liability, if the force, though known to be destructive, pursues an unexpected path.…Some acts, such as shooting are so imminently dangerous to anyone who may come within reach of the missile however unexpectedly, as to impose a duty of prevision not far from that of an insurer. Even today, and much oftener in earlier stages of the law, one acts sometimes at one’s peril.…These cases aside, wrong-is defined in terms of the natural or probable, at least when unintentional.…Negligence, like risk, is thus a term of relation.

Negligence in the abstract, apart from things related, is surely not a tort, if indeed it is understandable at all.…One who seeks redress at law does not make out a cause of action by showing without more that there has been damage to his person. If the harm was not willful, he must show that the act as to him had possibilities of danger so many and apparent as to entitle him to be protected against the doing of it though the harm was unintended.

* * *

The judgment of the Appellate Division and that of the Trial Term should be reversed, and the complaint dismissed, with costs in all courts.

Case questions

- Is there actual cause in this case? How can you tell?

- Why should Mrs. Palsgraf (or her insurance company) be made to pay for injuries that were caused by the negligence of the Long Island Rail Road?

- How is this accident not foreseeable?

Damages

Damages refer to the actual harm, injury, or loss suffered by the plaintiff as a result of the defendant's negligent action. To have a valid negligence claim, the plaintiff must show that they suffered some form of harm, whether it's physical injuries, financial losses, emotional distress, or damage to property. Damages are a critical component because without damages, there can be no claim.

The fear that she might be injured in the future is not a sufficient basis for a plaintiff to bring a lawsuit. This rule has proved troublesome in medical malpractice and industrial disease cases. A doctor’s negligent act or a company’s negligent exposure of a worker to some form of contamination might not become manifest in the body for years. In the meantime, the tort statute of limitations might have run out, barring the victim from suing at all. An increasing number of courts have eased the plaintiff’s predicament by ruling that the statute of limitations does not begin to run until the victim discovers that she has been injured or contracted a disease.

The law allows an exception to the general rule that damages must be shown when the plaintiff stands in danger of immediate injury from a hazardous activity. If you discover your neighbor experimenting with explosives in his basement, you could bring suit to enjoin him from further experimentation, even though he has not yet blown up his house—and yours.

Problems of Proof

The plaintiff in a tort suit, as in any other, has the burden of proving his allegations.

He must show that the defendant took the actions complained of as negligent, demonstrate the circumstances that make the actions negligent, and prove the occurrence and extent of injury. Factual issues are for the jury to resolve. Since it is frequently difficult to make out the requisite proof, the law allows certain presumptions and rules of evidence that ease the plaintiff’s burden, on the ground that without them substantial injustice would be done. One important rule goes by the Latin phrase res ipsa loquitur, meaning “the thing speaks for itself.” The best evidence is always the most direct evidence: an eyewitness account of the acts in question. But eyewitnesses are often unavailable, and in any event, they frequently cannot testify directly to the reasonableness of someone’s conduct, which inevitably can only be inferred from the circumstances.

In many cases, therefore, circumstantial evidence (evidence that is indirect) will be the only evidence or will constitute the bulk of the evidence. Circumstantial evidence can often be quite telling: though no one saw anyone leave the building, muddy footprints tracing a path along the sidewalk are fairly conclusive. Res ipsa loquitur is a rule of circumstantial evidence that permits the jury to draw an inference of negligence. A common statement of the rule is the following: “There must be reasonable evidence of negligence but where the thing is shown to be under the management of the defendant or his servants, and the accident is such as in the ordinary course of things does not happen if those who have the management use proper care, it affords reasonable evidence, in the absence of explanation by the defendants, that the accident arose from want of care.”

If a barrel of flour rolls out of a factory window and hits someone, or a soda bottle explodes, or an airplane crashes, courts in every state permit juries to conclude, in the absence of contrary explanations by the defendants, that there was negligence. The plaintiff is not put to the impossible task of explaining precisely how the accident occurred. A defendant can always offer evidence that he acted reasonably—for example, that the flour barrel was securely fastened and that a bolt of lightning, for which he was not responsible, broke its bands, causing it to roll out of the window. But testimony by the factory employees that they secured the barrel, in the absence of any further explanation, will not usually serve to rebut the inference. That the defendant was negligent does not conclude the inquiry or automatically entitle the plaintiff to a judgment. Tort law provides the defendant with several excuses, some of which are discussed briefly in the next section.

Excuses

There are more excuses (defenses) than are listed here, but contributory negligence or comparative negligence, assumption of risk, and act of God are among the principal defenses that will completely or partially excuse the negligence of the defendant.

Contributory and Comparative Negligence

Under an old common-law rule for contributory negligence, it was a complete defense to show that the plaintiff in a negligence suit was himself negligent. Even if the plaintiff was only mildly negligent, most of the fault being chargeable to the defendant, the court would dismiss the suit if the plaintiff’s conduct contributed to his injury. In a few states today, this rule of contributory negligence is still in effect. However, because the result of such a rule is manifestly unjust, this rule has been changed in many states to some version of comparative negligence. Under the rule of comparative negligence, damages are apportioned according to the degree of culpability of each of the parties involved. For example, if the plaintiff has sustained a $100,000 injury and is 20 percent responsible, the defendant will be liable for $80,000 in damages. In the Whitlock case (Case 4.2) above, at trial, the jury used comparative negligence to apportion responsibility between Plaintiff Whitlock and the University.

Assumption of Risk

Assumption of risk is a legal defense that a defendant can use in a negligence lawsuit if it can be shown that the plaintiff voluntarily and knowingly accepted the risks associated with a certain activity or situation, and therefore, the defendant should not be held liable for any resulting injuries or harm. In other words, the defendant asserts that the plaintiff cannot recover damages because they willingly exposed themselves to the danger and are responsible for their own injuries.

The assumption of risk doctrine arises in a few ways. The plaintiff may have formally agreed with the defendant before entering a risky situation that he will relieve the defendant of liability should injury occur. (“You can borrow my car if you agree not to sue me if the brakes fail, because they’re worn and I haven’t had a chance to replace them.”) Or the plaintiff may have entered into a relationship with the defendant knowing that the defendant is not in a position to protect him from known risks (the fan who is hit by a line drive in a ballpark). Or the plaintiff may act in the face of a risky situation known in advance to have been created by the defendant’s negligence (failure to leave, while there was an opportunity to do so, such as getting into an automobile when the driver is known to be drunk).

In some cases, the plaintiff might explicitly agree to waive their right to sue for injuries arising from a specific activity in a written waiver or release of liability. In still other situations, the actions of the plaintiff may show that they understand and accept the risk associated with certain activities like skydiving or rock climbing.

Act of God

Technically, the rule that no one is responsible for an “act of God,” or force majeure as it is sometimes called, is not an excuse but a defense premised on a lack of causation. If a force of nature caused the harm, then the defendant was not negligent in the first place. A marina, obligated to look after boats moored at its dock, is not liable if a sudden and fierce storm against which no precaution was possible destroys someone’s vessel. However, if it is foreseeable that harm will result from a negligent condition triggered by a natural event, then there is liability. For example, a work crew failed to remove residue explosive gas from an oil barge. Lightning hit the barge, exploded the gas, and injured several workmen. The plaintiff recovered damages against the company because the negligence consisted of the failure to guard against any one of a number of chance occurrences that could ignite the gas.

Vicarious Liability

Liability for negligent acts does not always end with the one who was negligent. Under certain circumstances, the liability is imputed to others. For example, an employer is responsible for the negligence of his employees if they were acting in the scope of employment. This rule of vicarious liability is often called respondeat superior, meaning that the higher authority must respond to claims brought against one of its agents. Respondeat superior is not limited to the employment relationship but extends to a number of other agency relationships as well.

Legislatures in many states have enacted laws that make people vicariously liable for acts of certain people with whom they have a relationship, though not necessarily one of agency. It is common, for example, for the owner of an automobile to be liable for the negligence of one to whom the owner lends the car. So-called dram shop statutes place liability on bar and tavern owners and others who serve too much alcohol to one who, in an intoxicated state, later causes injury to others. In these situations, although the injurious act of the drinker stemmed from negligence, the one whom the law holds vicariously liable (the bartender) is not himself necessarily negligent—the law is holding him strictly liable, and to this concept we now turn.

4.5 Strict Liability

Thus far, we have considered principles of liability that in some sense depend upon the “fault” of the tortfeasor. In intentional torts, the concept of "fault" relates to the deliberate and intentional actions of the defendant that led to harm or injury to the plaintiff. The fault in negligence cases can be seen in the defendant's failure to meet a certain standard of care. Strict liability is a legal doctrine that holds a party legally responsible for certain actions or activities, regardless of their fault. In strict liability cases, the focus is not on whether the defendant acted negligently or intentionally, but rather on whether they engaged in a certain activity that caused harm, even if they took precautions to prevent that harm.

Strict liability cases do not require proving the defendant's intent or fault. The focus is on the act itself and its consequences. Strict liability often applies to activities or products that are considered inherently dangerous or pose significant risks to the public. Examples include storing hazardous materials, keeping wild animals, and manufacturing certain products.

Hazardous Activities

it has long been held that someone who engages in ultrahazardous (or sometimes, abnormally dangerous) activities is liable for damage that he causes, even though he has taken every possible precaution to avoid harm to someone else. Strict liability often applies to ultrahazardous activities, which are inherently dangerous actions that have the potential to cause significant harm or damage. The concept of strict liability in hazardous activities means that those who engage in such activities can be held legally responsible for any harm that occurs, regardless of their intent or level of care. Examples of such activities include setting explosives, handling toxic materials, operating heavy machinery, blasting operations, storing and transporting hazardous chemicals, and operating power plants.

Activity 4D

Debate: Strict Liability

Strict liability, or liability without fault, is often justified as promoting public safety. Does it?

Search the internet for an article that addresses the reasons for holding defendants strictly liable even when there is no fault behind an injury. Does this promote public safety? Would society be better served if negligence were required to hold a defendant liable in the event of an injury?

Animals

Strict liability can apply to cases involving damages caused by animals, particularly those that are considered inherently dangerous or have a propensity for causing harm. Animal owners can be held strictly liable for any injuries or damages their animals cause, regardless of whether the owner was negligent or had knowledge of the animal's behavior. This can include wild animals, certain breeds of dogs with aggressive tendencies, and animals that are commonly used for their strength or guarding abilities. Unlike negligence cases, where the plaintiff needs to prove that the defendant's lack of reasonable care led to the harm, strict liability doesn't require proving negligence. In cases involving dangerous animals, the owner can be held liable for any injuries caused by their animal, even if they took precautions to prevent harm.

Case 4.4

Klein v. Pyrodyne Corporation, 810 P.2d 917 (Supreme Court of Washington, 1991)

Pyrodyne Corporation (Pyrodyne) is a licensed fireworks display company that contracted to display fireworks at the Western Washington State Fairgrounds in Puyallup, Washington, on July 4, 1987. During the fireworks display, one of the mortar launchers discharged a rocket on a horizontal trajectory parallel to the earth. The rocket exploded near a crowd of onlookers, including Danny Klein. Klein’s clothing was set on fire, and he suffered facial burns and serious injury to his eyes. Klein sued Pyrodyne for strict liability to recover for his injuries. Pyrodyne asserted that the Chinese manufacturer of the fireworks was negligent in producing the rocket and therefore Pyrodyne should not be held liable. The trial court applied the doctrine of strict liability and held in favor of Klein. Pyrodyne appealed.

Section 519 of the Restatement (Second) of Torts provides that any party carrying on an “abnormally dangerous activity” is strictly liable for ensuing damages. The public display of fireworks fits this definition. The court stated: “Any time a person ignites rockets with the intention of sending them aloft to explode in the presence of large crowds of people, a high risk of serious personal injury or property damage is created. That risk arises because of the possibility that a rocket will malfunction or be misdirected.” Pyrodyne argued that its liability was cut off by the Chinese manufacturer’s negligence. The court rejected this argument, stating, “Even if negligence may properly be regarded as an intervening cause, it cannot function to relieve Pyrodyne from strict liability.”

The Washington Supreme Court held that the public display of fireworks is an abnormally dangerous activity that warrants the imposition of strict liability.

Affirmed.

Case questions

- Why would certain activities be deemed ultrahazardous or abnormally dangerous so that strict liability is imposed?

- If the activities are known to be abnormally dangerous, did Klein assume the risk?

- Assume that the fireworks were negligently manufactured in China. Should Klein’s only remedy be against the Chinese company, as Pyrodyne argues? Why or why not?

Strict Liability for Products

Strict liability may also apply as a legal standard for products, even those that are not ultrahazardous. Strict product liability was initially was created by a California Supreme Court decision in the 1962 case of Greenman v. Yuba Power Products, Inc. In Greenman, the plaintiff had used a home power saw and bench, the Shopsmith, designed and manufactured by the defendant. He was experienced in using power tools and was injured while using the approved lathe attachment to the Shopsmith to fashion a wooden chalice. The case was decided on the premise that Greenman had done nothing wrong in using the machine but that the machine had a defect that was “latent” (not easily discoverable by the consumer). Rather than decide the case based on warranties, or by requiring that Greenman prove how the defendant had been negligent, Justice Traynor found for the plaintiff based on the overall social utility of strict liability in cases of defective products. According to his decision, the purpose of such liability is to ensure that the “cost of injuries resulting from defective products is borne by the manufacturers…rather than by the injured persons who are powerless to protect themselves.”

Today, the majority of U.S. states recognize strict liability for defective products, although some states limit strict liability actions to damages for personal injuries rather than property damage. Injured plaintiffs have to prove the product caused the harm but do not have to prove exactly how the manufacturer was careless. Purchasers of the product, as well as injured guests, bystanders, and others with no direct relationship to the product, may sue for damages caused by the product.

The Restatement specifies six requirements all of which must be met for a plaintiff to recover using strict liability for a product that the plaintiff claims is defective:

- The product must be in a defective condition when the defendant sells it.

- The defendant must normally be engaged in the business of selling or otherwise distributing the product.

- The product must be unreasonably dangerous to the user or consumer because of its defective condition.

- The plaintiff must incur physical harm to self or to property by using or consuming the product.

- The defective condition must be the proximate cause of the injury or damage.

- The goods must not have been substantially changed from the time the product was sold to the time the injury was sustained.

For defendants, who can include manufacturers, distributors, processors, assemblers, packagers, bottlers, retailers, and wholesalers, there are a number of defenses that are available, including assumption of risk, product misuse and comparative negligence, commonly known dangers, and the knowledgeable-user defense. We have already seen assumption of risk and comparative negligence in terms of negligence actions; the application of these is similar in products-liability actions.

Under product misuse, a plaintiff who uses a product in an unexpected and unusual way will not recover for injuries caused by such misuse. For example, suppose that someone uses a rotary lawn mower to trim a hedge and that after twenty minutes of such use loses control of the mower because of its weight and suffers serious cuts to his abdomen after dropping it. Here, there would be a defense of product misuse, as well as contributory negligence. Consider the urban (or Internet) legend of Mervin Gratz, who supposedly put his Winnebago on autopilot to go back and make coffee in the kitchen, then recovered millions after his Winnebago turned over and he suffered serious injuries. There are multiple defenses to this alleged action; these would include the defenses of contributory negligence, comparative negligence, and product misuse. (There was never any such case, and certainly no such recovery; it is not known who started this legend, or why.)

Another defense against strict liability as a cause of action is the knowledgeable-user defense. If the parents of obese teenagers bring a lawsuit against McDonald’s, claiming that its fast-food products are defective and that McDonald’s should have warned customers of the adverse health effects of eating its products, a defense based on the knowledgeable user is available. In one case, the court found that the high levels of cholesterol, fat, salt, and sugar in McDonald’s food is well known to users. The court stated, “If consumers know (or reasonably should know) the potential ill health effects of eating at McDonald’s, they cannot blame McDonald’s if they, nonetheless, choose to satiate their appetite with a surfeit of supersized McDonald’s products.”

- A woman fell ill in a store. An employee put the woman in an infirmary but provided no medical care for six hours, and she died. The woman’s family sued the store for wrongful death. What arguments could the store make that it was not liable? What arguments could the family make? Which seem the stronger arguments? Why?

- The signals on a railroad crossing are defective. Although the railroad company was notified of the problem a month earlier, the railroad inspector has failed to come by and repair them. Seeing the all-clear signal, a car drives up and stalls on the tracks as a train rounds the bend. For the past two weeks the car had been stalling, and the driver kept putting off taking the car to the shop for a tune-up. As the train rounds the bend, the engineer is distracted by a conductor and does not see the car until it is too late to stop. Who is negligent? Who must bear the liability for the damage to the car and to the train?

- Suppose in the Katko v. Briney case that instead of setting such a device, the defendants had simply let the floor immediately inside the front door rot until it was so weak that anybody who came in and took two steps straight ahead would fall through the floor and to the cellar. Will the defendant be liable in this case? What if they invited a realtor to appraise the place and did not warn her of the floor? Does it matter whether the injured person is a trespasser or an invitee?

- Plaintiff’s husband died in an accident, leaving her with several children and no money except a valid insurance policy by which she was entitled to $5,000. Insurance Company refused to pay, delaying and refusing payment and meanwhile “inviting” Plaintiff to accept less than $5,000, hinting that it had a defense. Plaintiff was reduced to accepting housing and charity from relatives. She sued the insurance company for bad-faith refusal to settle the claim and for the intentional infliction of emotional distress. The lower court dismissed the case. Should the court of appeals allow the matter to proceed to trial?

References

Johnson v. Kosmos Portland Cement Co., 64 F.2d 193 (6th Cir. 1933).

Katko v. Briney, 183 N.W.2d 657 (Iowa 1971).

New York Times v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964).

Pellman v. McDonald’s Corp., 237 F.2d 512 (S.D.N.Y. 2003).

Restatement (Second) of Torts, Section 559 (1965).

Scott v. London & St. Katherine Docks Co., 3 H. & C. 596, 159 Eng.Rep. 665 (Q.B. 1865).

Tarasoff v. Regents of University of California, 551 P.2d 334 (Calif. 1976).

physical or mental damage

1) the money awarded to one party because of an injury or loss caused by another party; and 2) the harm an injured party suffers because of another party's wrongful conduct

a deliberate act that causes harm to another, and for which the injured person may sue the wrongdoer for damages

a tort claim that arises when a person or entity is careless and that carelessness injures or harms someone

a tort in which liability is imposed without regard to fault

the state of being legally responsible for something

a person who commits an intentional or negligent tort—a wrongful act that harms another

responsibility for wrongdoing or failure

(1) the threat of immediate harm or offense of contact or (2) any act that would arouse reasonable apprehension of imminent harm

unauthorized and harmful or offensive physical contact with another person that causes injury

failure to use reasonable care, resulting in injury or property damage to another

a wrongful act that causes injury

a legal claim that allows individuals to seek compensation for severe emotional distress or mental anguish caused by the intentional and outrageous conduct of another party

intentionally going on land that belongs to someone else or putting something on someone else’s property and refusing to remove it