Chapter 2 – Courts and the Legal Process

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe the two different court systems in the United States, and explain why some cases can be filed in either court system.

- Explain the importance of subject matter jurisdiction and personal jurisdiction and know the difference between the two.

- Describe the various stages of a civil action: from pleadings, to discovery, to trial, and to appeals.

2.1 General Perspectives on Courts and the Legal Process

In the United States, law and government are interdependent. The Constitution establishes the basic framework of government and imposes certain limitations on the powers of government. In turn, the various branches of government are intimately involved in making, enforcing, and interpreting the law. Today, much of the law comes from Congress and the state legislatures. But it is in the courts that legislation is interpreted and prior case law is interpreted and applied.

As we go through this chapter, consider the case of Harry and Kay Robinson summarized below.

Robinson v. Audi

Harry and Kay Robinson purchased a new Audi automobile from Seaway Volkswagen, Inc. (Seaway), in Massena, New York, in 1976. The following year the Robinson family, who resided in New York, left that state for a new home in Arizona. As they passed through Oklahoma, another car struck their Audi in the rear, causing a fire that severely burned Kay Robinson and her two children. Later on, the Robinsons brought a products-liability action in the District Court for Creek County, Oklahoma, claiming that their injuries resulted from the defective design and placement of the Audi’s gas tank and fuel system. They sued numerous defendants, including the automobile’s manufacturer, Audi NSU Auto Union Aktiengesellschaft (Audi); its importer, Volkswagen of America, Inc. (Volkswagen); its regional distributor, World-Wide Volkswagen Corp. (World-Wide); and its retail dealer, Seaway.

A case like this raises several questions that this Chapter can help you answer. In which court should the Robinsons file their action? Can the Oklahoma court hear the case and make a judgment that will be enforceable against all of the defendants? Which law will the court use to come to a decision? Will it use New York law, Oklahoma law, federal law, or German law?

Should the Robinsons bring their action in state court or in federal court? Over which of the defendants will the court have personal jurisdiction?

2.2 The Relationship between State and Federal Court Systems in the United States

Although it is sometimes said that there are two separate court systems, the reality is more complex. There are more than fifty court systems in the United States. Each state has its own court system, there is a local court system in the District of Columbia, and of course there is the federal court system. While these are all separate court systems, there are points of contact between them.

Courts must honor the laws of other states, and must also honor federal law. To understand what this means, let’s review how state laws and federal laws might come into contact. First, under the Supremacy Clause of the United States Constitution, state courts must honor federal law where state laws are in conflict with federal law. Second, claims arising under federal statutes can be tried in the state courts as long as the Constitution or Congress has not explicitly required that only federal courts can hear that kind of claim. Third, under the full faith and credit clause, each state court is obligated to respect the final judgments of courts in other states. Thus, a contract dispute resolved by an Arkansas court cannot be relitigated in North Dakota when the plaintiff wants to collect on the Arkansas judgment in North Dakota. Fourth, state courts often must consider the laws of other states in deciding cases involving issues where two states have an interest, such as when drivers from two different states collide in a third state. Under these circumstances, state judges will consult their own state’s case decisions involving conflicts of laws and sometimes decide that they must apply another state’s laws to decide the case.

Just as state courts are concerned with federal law, so too are federal courts often concerned with state law and with what happens in state courts. Federal courts will consider state-law-based claims when a case involves claims using both state and federal law. Claims based on federal laws will permit the federal court to take jurisdiction over the whole case, including any state issues raised. In those cases, the federal court is said to exercise pendent jurisdiction over the state claims. Also, the Supreme Court will occasionally take appeals from a state supreme court where state law raises an important issue of federal law to be decided. For example, a convict on death row may claim that the state’s chosen method of execution using the injection of drugs is unusually painful and involves “cruel and unusual punishment,” raising an Eighth Amendment issue.

Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction is an essential concept in understanding courts and the legal system. Jurisdiction is a combination of two Latin words: juris (law) and diction (to speak). Which court has the power “to speak the law” is the basic question of jurisdiction. Jurisdiction therefore refers to the legal authority or power that a court governing body has over a particular geographical area, subject matter, or individuals. In order to decide a claim or controversy, a Court must have jurisdiction over that claim, the parties in the suit, and geographic area in which the claim arose. Jurisdiction determines which Court has the right to hear and decide legal cases and make rulings that bind the parties on various matters. Jurisdiction ensures that legal proceedings are conducted within a defined framework and that decisions are binding and enforceable.

Subject Matter Jurisdiction - Filing in Federal Court

The decision of whether a case can be heard in the federal courts is a question of subject matter jurisdiction. Federal court jurisdiction is based on the types of cases outlined in Article III of the Constitution. Generally, federal courts have jurisdiction over cases in the following situations, meaning that these cases can be filed in federal courts.

Federal Question Jurisdiction: Federal courts have jurisdiction over cases that involve a federal law, treaty, or the interpretation of the U.S. Constitution. If the legal dispute centers around a question of federal law, it can be brought in federal court. For example, cases involving violations of federal statutes like civil rights laws, antitrust laws, or intellectual property laws often fall under federal question jurisdiction, and therefore such cases can originate in the federal courts.

Diversity of Citizenship Jurisdiction: Federal courts can hear cases between parties from different states if the amount in controversy exceeds a certain threshold (currently $75,000). In these cases, the federal courts are applying state law to decide a case. This is intended to provide a neutral forum when parties from different states are involved in a dispute, and it helps prevent bias that might arise in state courts. For example, a citizen of New Jersey may sue a citizen of New York over a contract dispute in federal court, but if both were citizens of New Jersey, the plaintiff would be limited to the state courts. The Constitution establishes diversity jurisdiction to avoid any hostility of the local courts toward people from other states. In 2020 more than 40% of all lawsuits filed in federal court were based on diversity of citizenship. In a diversity of citizenship case, the plaintiff may choose to file in federal court. Or, the plaintiff may file in their home state court, and the defendant in turn may ask for removal to federal court on the basis of diversity. This may be because litigants sometimes believe that there would be a “home-court advantage” for an in-state plaintiff who brings a lawsuit against a nonresident in his local state court.

Along with these two main ways to establish subject matter jurisdiction in the federal courts, there are some other cases that originate in federal court - admiralty cases, cases between states, and bankruptcy cases among them.

The Federal Court System

The federal judicial system is uniform throughout the United States and consists of three levels: the district courts, the courts of appeal and the United States Supreme Court.

District Courts

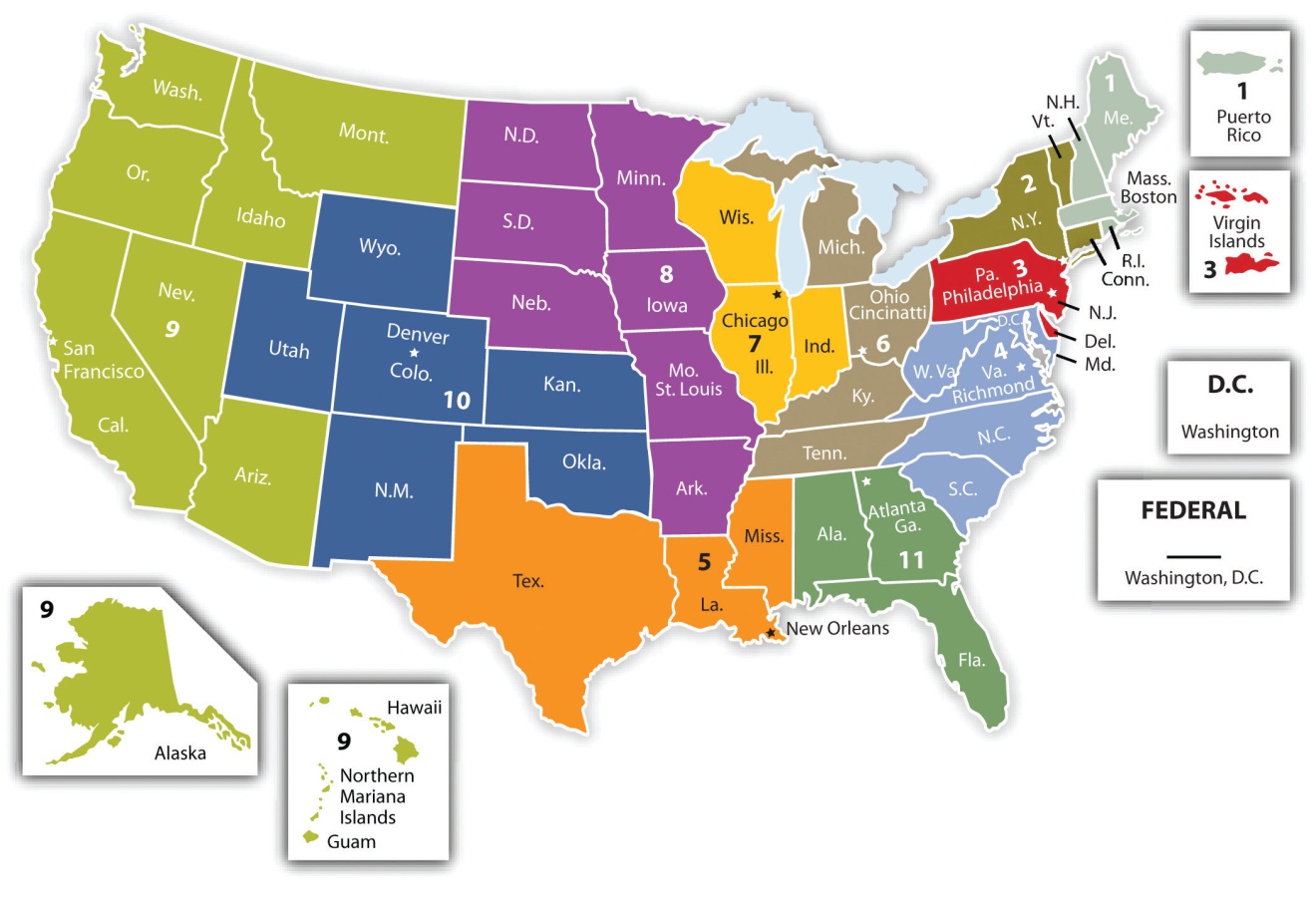

At the first level are the federal district courts, which are the trial courts in the federal system. Every state has one or more federal districts; the less populous states have one, and the more populous states (California, Texas, and New York) have four. New Jersey has one federal District Court.

Courts of Appeal

Cases from the district courts can then be appealed to the circuit courts of appeal, of which there are thirteen. Each circuit oversees the work of the district courts in several states. For example, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit hears appeals from district courts in New York, Connecticut, and Vermont. New Jersey is part of the Third Circuit, which also hears appeals from the district courts in Pennsylvania, Delaware, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Appeals are usually heard by three-judge panels, but sometimes there will be a rehearing at the court of appeals level, in which case all judges sit to hear the case “en banc.”

United States Supreme Court

Overseeing all federal courts is the U.S. Supreme Court, in Washington, DC. It consists of nine justices—the chief justice and eight associate justices. (This number is not constitutionally required; Congress can establish any number. It has been set at nine since after the Civil War.) The Supreme Court has selective control over most of its docket. By law, the cases it hears represent only a tiny fraction of the cases that are submitted. In the 2022 term, the Supreme Court had numerous petitions (over 7,000, not including thousands of petitions from prisoners) but decided only 58 cases. All the justices hear and consider each case together, unless a justice has a conflict of interest and must withdraw from hearing the case.

Figure 2.1 The Federal Judicial Circuits

Federal judges—including Supreme Court justices—are nominated by the president and must be confirmed by the Senate. Unlike state judges, who are usually elected and preside for a fixed term of years, federal judges sit for life unless they voluntarily retire or are impeached.

Exclusive Jurisdiction in Federal Courts

There are some cases that can only be heard in the federal courts. In other words, these types of cases cannot be filed in the state court systems. These cases are listed in Article III of the U.S. Constitution and include:

- cases in which two or more states are a party

- cases involving ambassadors and other high-ranking public figures

- federal crimes

- bankruptcy

- patent, copyright, and trademark cases

- cases involving Securities and banking regulation

In addition, other cases can be specified by federal statute where Congress declares that federal courts will have exclusive jurisdiction.

Subject Matter Jurisdiction - Filing in State Court

When a dispute does not fall within the specific jurisdiction of federal courts, the resulting case will be filed in state court. State courts have jurisdiction over a wide range of legal matters not filed in the federal courts. Basically, when a case cannot be filed in federal court because the federal courts do not have jurisdiction, the only choice for jurisdiction would be to file in state court. The vast majority of civil lawsuits in the United States are filed in state courts.

The State Court Systems

A typical state court system in the United States looks a lot like the federal court system, with three levels of courts that handle a wide range of legal matters arising under state laws. While the structure and terminology can vary from state to state, the following is a general overview of the components that might be found in a state court system.

State Trial Courts

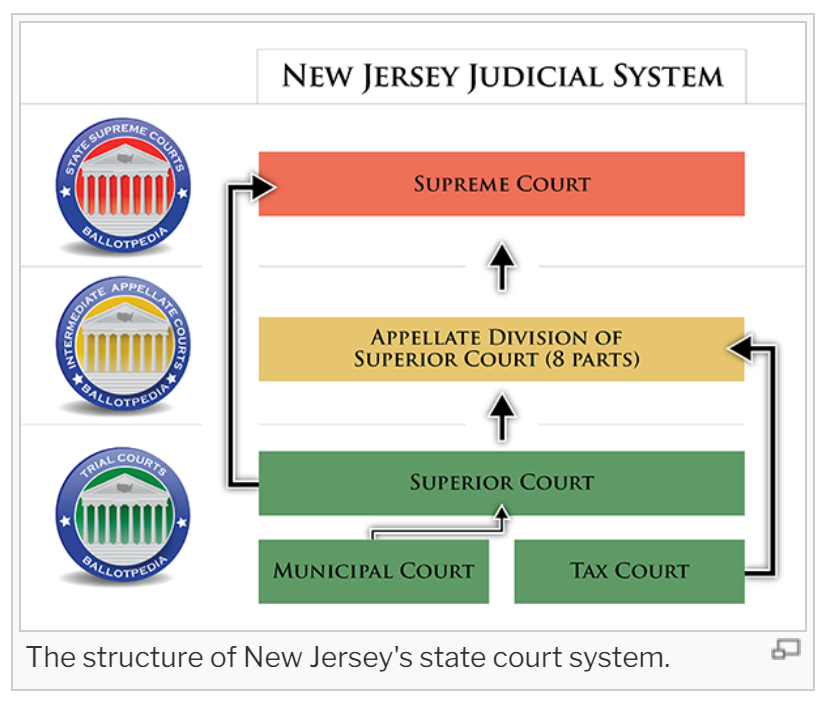

Each state will have a court that functions as its general trial court, which is going to be the court in which most cases will originate. In New Jersey, this court is the Superior Court.

State Intermediate Appellate Courts

Most, but not all, states have an intermediate appeals court that hears appeals from the state trial court. Whether or not a state has an intermediate appeals court will be established in its state constitution. These courts primarily handle appeals, ensuring that legal errors or misinterpretations are corrected. Court appeals in New Jersey go through the Appellate Division of the Superior Court.

State Supreme Court

This is the highest court in a state's judicial system. It has discretionary review authority over cases and provides final interpretation of state laws and constitution within the state. It often focuses on important legal questions and issues of public policy. In New Jersey, the highest court is called the New Jersey Supreme Court

Activity 2A

Appointed v. Elected Judges

There is no uniform way of selecting judges in state courts. The majority of states hold elections for the judiciary, with some states using partisan platforms for their judicial elections, and others using a non-partisan election process where judges run not with a political party, but rather on qualifications and experience. Some states have limited terms for elected judges, while in other states an election might lead to a lifetime seat on the judicial bench in a retention election. Other states, like New Jersey, use an appointment process for members of the judiciary, where judges are appointed by the state Governor either for a fixed term or for a lifetime appointment.

Research at least one internet source about judicial selection and length of judicial service and its impact on judicial independence, accountability, impartiality, public perception, and the overall effectiveness of the judiciary. Would it better serve society if judges were elected by the people, or appointed by a Governor or other political body? Should judges serve for a term, or for a lifetime seat? And if for a lifetime seat, are there any circumstances under which judges should be removed?

Figure 2.2 The New Jersey State Court System

This image comes from the website Ballotpedia.org. It is suitable for reuse under GFDL licensing.

Subject Matter Jurisdiction – Limited versus General Jurisdiction Courts

Most cases that are filed in a Court system are filed in a court of general jurisdiction. A court of general jurisdiction has the authority to hear and decide a wide variety of cases, both civil and criminal, without being limited to specific subject matters or certain types of legal disputes. These courts are designed to handle a broad spectrum of legal issues and provide a forum for parties to resolve a wide range of disputes under the law. In the federal system, a Court of General Jurisdiction is the District Court. In New Jersey, an example of a court of general jurisdiction is the Superior Court, where trials are held. State courts of general jurisdiction hear cases involving incidents such as automobile accidents and injuries, or breaches of contract. They also try cases involving serious crimes. Decisions in courts of general jurisdiction are often made by juries.

Court systems also have courts of limited jurisdiction. These are courts that hear only certain types of cases – either cases that are specialized to a specific area of the law only, or cases that are considered smaller cases than would typically be heard by a court of general jurisdiction. For example, a state court that only hears landlord-tenant types of cases would be a court of limited jurisdiction to this specific area of law. In New Jersey, there is a tax court which is a specialized court hears cases involving disputes related to state taxation, including property taxes, income taxes, and other tax matters. There are also several specialized courts in the federal judicial system. These include the U.S. Tax Court, the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals, and the Court of Claims.

Limited jurisdiction courts can also include county or municipal courts that hear minor criminal cases (petty assaults, traffic offenses, and breach of peace, among others) and civil cases involving monetary amounts up to a fixed ceiling (no more than $10,000 in most states and far less in many states). Limited jurisdiction courts handle many cases, with estimates up to 80% of all cases filed in state court systems. One familiar limited jurisdiction state court is the small claims court, with jurisdiction to hear civil cases involving claims for amounts ranging between $1,000 and $5,000 in about half the states and for considerably less in the other states ($500 to $1,000). The advantage of the small claims court is that its procedures are informal, and lawyers are not necessary to present the case.

Decisions in limited jurisdiction courts are made by judges, and are usually considered final. If a party is dissatisfied with the outcome, typically that party will be able to get a new trial in a court of general jurisdiction. Because there has been one trial already, this is known as a trial de novo. It is not an appeal, since the case essentially starts over.

2.3 Subject Matter Jurisdiction – Original versus Appellate Jurisdiction

Two aspects of civil lawsuits are common to all state courts: trials and appeals. A court exercising a trial function has original jurisdiction—that is, jurisdiction to determine the facts of the case and apply the law to them. A court that hears appeals from the trial court is said to have appellate jurisdiction—it must accept the facts as determined by the trial court and limit its review to the lower court’s theory of the applicable law.

Original jurisdiction refers to the authority of a court to hear and decide a case when it is first filed. Original jurisdiction courts are also called courts of “first resort.” This is the court that is the initial forum for legal proceedings, where the case is presented, evidence is introduced, witnesses are heard, and a decision is reached on the merits of the case. Usually this is the trial court.

In contrast, appellate courts have appellate jurisdiction, which means they have the authority to review decisions made by lower courts, including courts of original jurisdiction. Appellate Courts do not reexamine the facts of the case but focus on legal issues, procedural errors, and the application of the law. For example, the appellant (the losing party who appeals) might complain that the judge wrongly instructed the jury on the meaning of the law, or improperly allowed testimony of a particular witness, or misconstrued the law in question. The appellee (who won in the lower court) will ask that the appellant be denied—usually this means that the appellee wants the lower-court judgment affirmed. The appellate court, which usually includes at least three judges, has quite a few choices: it can affirm, modify, reverse, or reverse and remand the lower court (return the case to the lower court for retrial).

Typically, a case will begin in a court of original jurisdiction, with the losing party having a right to appeal to a court of appellate jurisdiction. In many states in and in the federal system this would be the intermediate appellate court, which are usually composed of a panel of three judges. After the one appeal of right, further appeals by either party to the same or higher appeals court are discretionary. Should the highest court chose to hear the case, a single panel of between five and nine judges, typically located in the state capital, will review the case and decision of the lower court. For most litigants in state court, the ruling of the state supreme court is final. In a relatively small class of cases—those in which federal constitutional claims are made—appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court to issue a writ of certiorari remains a possibility.

Concurrent Jurisdiction

When a plaintiff takes a case to state court, it will be because state courts typically hear that kind of case (i.e., there is subject matter jurisdiction). If the plaintiff’s main cause of action comes from a certain state’s constitution, statutes, or court decisions, the state courts have subject matter jurisdiction over the case. If the plaintiff’s main cause of action is based on federal law (e.g., Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964), the federal courts have subject matter jurisdiction over the case. But federal courts will also have subject matter jurisdiction over certain cases that have only a state-based cause of action; those cases are ones in which the plaintiff(s) and the defendant(s) are from different states and the amount in controversy is more than $75,000. State courts can have subject matter jurisdiction over certain cases that have only a federal-based cause of action. The Supreme Court has now made clear that state courts have concurrent jurisdiction of any federal cause of action unless Congress has given exclusive jurisdiction to federal courts.

In short, a case with a federal question can be often be heard in either state or federal court, and a case that has parties with a diversity of citizenship can be heard in state courts or in federal courts where the tests of complete diversity and amount in controversy are met.

Whether a case will be heard in a state court or moved to a federal court will depend on the parties. If a plaintiff files a case in state trial court where concurrent jurisdiction applies, a defendant may (or may not) ask that the case be removed to federal district court.

Robinson v. Audi

Now consider Mr. and Mrs. Robinson and their products-liability claim against Seaway Volkswagen and the other three defendants. There is no federal products-liability law that could be used as a cause of action. They are most likely suing the defendants using products-liability law based on common-law negligence or common-law strict liability law, as found in state court cases. They were not yet Arizona residents at the time of the accident, and their accident does not establish them as Oklahoma residents, either. They bought the vehicle in New York from a New York–based retailer. None of the other defendants is from Oklahoma.

They file in an Oklahoma state court, but how will their attorney or the court know if the state court has subject matter jurisdiction? Unless the case is required to be in a federal court (i.e., unless the federal courts have exclusive jurisdiction over this kind of case), any state court system will have subject matter jurisdiction, including Oklahoma’s state court system. But if their claim is for a significant amount of money, they cannot file in small claims court, probate court, or any court in Oklahoma that does not have statutory jurisdiction over their claim. They will need to file in a court of general jurisdiction. In short, even filing in the right court system (state versus federal), the plaintiff must be careful to find the court that has subject matter jurisdiction.

If they wish to go to federal court, can they? There is no federal question presented here (the claim is based on state common law), and the United States is not a party, so the only basis for federal court jurisdiction would be diversity jurisdiction. If enough time has elapsed since the accident and they have established themselves as Arizona residents, they could sue in federal court in Oklahoma (or elsewhere), but only if none of the defendants—the retailer, the regional Volkswagen company, Volkswagen of North America, or Audi (in Germany) are incorporated in or have a principal place of business in Arizona. The federal judge would decide the case using federal civil procedure but would have to make the appropriate choice of state law. In this case, the choice of conflicting laws would most likely be Oklahoma, where the accident happened, or New York, where the defective product was sold.

Choice of Law and Choice of Forum Clauses

Sometimes parties decide in advance of a dispute what law will apply to their claims and what court they will file in. Such decisions are made in a written contract, and courts will honor contractual choices of parties in a lawsuit. Suppose the parties to a contract wind up in court arguing over the application of the contract’s terms. If the parties are from two different states, the judge may have difficulty determining which law to apply. But if the contract says that a particular state’s law will be applied if there is a dispute, then ordinarily the judge will apply that state’s law as a rule of decision in the case. For example, Kumar Patel (a Missouri resident) opens a brokerage account with Goldman, Sachs and Co., and the contractual agreement calls for “any disputes arising under this agreement” to be determined “according to the laws of the state of New York.” When Kumar claims in a Missouri court that his broker is “churning” his account, and, on the other hand, Goldman, Sachs claims that Kumar has failed to meet his margin call and owes $38,568.25 (plus interest and attorney’s fees), the judge in Missouri will apply New York law based on the contract between Kumar and Goldman, Sachs.

Ordinarily, a choice-of-law clause will be accompanied by a choice-of-forum clause. In a choice-of-forum clause, the parties in the contract specify which court they will go to in the event of a dispute arising under the terms of contract. For example, Harold (a resident of Virginia) rents a car from Alamo at the Denver International Airport. He does not look at the fine print on the contract. He also waives all collision and other insurance that Alamo offers at the time of his rental. While driving back from Telluride Bluegrass Festival, he has an accident in Idaho Springs, Colorado. His rented Nissan Altima is badly damaged. On returning to Virginia, he would like to settle up with Alamo, but his insurance company and Alamo cannot come to terms. He realizes, however, that he has agreed to hear the dispute with Alamo in a specific court in San Antonio, Texas. In the absence of fraud or bad faith, any court in the United States is likely to uphold the choice-of-form clause and require Harold (or his insurance company) to litigate in San Antonio, Texas.

Figure 2.3 Sample Conflict-of-Law Principles

|

Substantive Law Issue |

Law to be Applied |

|

Liability for injury caused by tortious conduct |

State in which the injury was inflicted |

|

Real property |

State where the property is located |

|

Personal Property: inheritance |

Domicile of deceased (not location of property) |

|

Contract: validity |

State in which contract was made |

|

Contract: breach |

State in which contract was to be performed* |

|

*Or, in many states, the state with the most significant contacts with the contractual activities |

|

|

Note: Choice-of-law clauses in a contract will ordinarily be honored by judges in state and federal courts. |

|

2.4 Personal Jurisdiction

Personal jurisdiction, also known as "in personam jurisdiction," refers to a court's authority to make decisions and issue rulings that are legally binding on a specific individual or entity involved in a legal case. It pertains to the court's power over the parties themselves, as opposed to subject matter jurisdiction (which we explored above) which focuses on the court's authority over the type of case being heard.

In order for a court to exercise personal jurisdiction over a party, certain conditions or connections must be established. These conditions generally involve the defendant's contacts with the jurisdiction in which the court is located. Note that this analysis does not focus on the Plaintiff. The Court must still have jurisdiction over the Plaintiff, but as the filing party, the Plaintiff consents to the jurisdiction of the court that they choose to file in.

As to the Defendant, there are two ways to obtain jurisdiction and both are related to the defendant's activities within the jurisdiction. General personal jurisdiction is typically established when a defendant has significant and continuous contacts with the jurisdiction, such as maintaining a residence or conducting substantial business activities there. In other words, the physical presence of the Defendant within the area the court serves provides jurisdiction over the Defendant for purposes of litigation. This means that personal jurisdiction of a state court over persons is clear for those defendants found within the state.

At times, a lawsuit is filed against a Defendant that is not ordinarily present in the area served by the Court, such as an out-of-state Defendant. In this situation, jurisdiction can still be obtained by establishing that the Defendant has sufficient minimum contacts with the forum.

The minimum contacts test was established by the U.S. Supreme Court in the landmark case International Shoe Co. v. Washington (1945). The test considers whether a defendant's connections or activities within a particular jurisdiction are substantial enough to warrant that jurisdiction's courts asserting personal jurisdiction over the defendant. The defendant has minimum contacts if he has purposefully availed himself of the benefits and protections of the jurisdiction in question such that he could reasonably foresee that they could be subject to lawsuits in that jurisdiction.

Almost every state in the United States has a statute regarding personal jurisdiction, instructing judges when it is permissible to assert personal jurisdiction over an out-of-state resident. These are called long-arm statutes. But no state can reach out beyond the limits of what is constitutionally permissible under the Fourteenth Amendment, which binds the states with its proviso to guarantee the due process rights of the citizens of every state in the union.

In sum, the exercise of personal jurisdiction over the defendant must be consistent with due process and any statutes in that state that prescribe the jurisdictional reach of that state.

Case 2.1

Burger King Corp. v. Rudzewicz, 471 U.S. 462 (U.S. Supreme Court 1985)

Summary

Burger King Corp. is a Florida corporation with principal offices in Miami. It principally conducts restaurant business through franchisees. The franchisees are licensed to use Burger King’s trademarks and service marks in standardized restaurant facilities. Rudzewicz is a Michigan resident who, with a partner (MacShara) operated a Burger King franchise in Drayton Plains, Michigan. Negotiations for setting up the franchise occurred in 1978 largely between Rudzewicz, his partner, and a regional office of Burger King in Birmingham, Michigan, although some deals and concessions were made by Burger King in Florida. A preliminary agreement was signed in February of 1979. Rudzewicz and MacShara assumed operation of an existing facility in Drayton Plains and MacShara attended prescribed management courses in Miami during the four months following Feb. 1979.

Rudzewicz and MacShara bought $165,000 worth of restaurant equipment from Burger King’s Davmor Industries division in Miami. But before the final agreements were signed, the parties began to disagree over site-development fees, building design, computation of monthly rent, and whether Rudzewicz and MacShara could assign their liabilities to a corporation they had formed. Negotiations took place between Rudzewicz, MacShara, and the Birmingham regional office; but Rudzewicz and MacShara learned that the regional office had limited decision-making power and turned directly to Miami headquarters for their concerns. The final agreement was signed by June 1979 and provided that the franchise relationship was governed by Florida law, and called for payment of all required fees and forwarding of all relevant notices to Miami headquarters.

The Drayton Plains restaurant did fairly well at first, but a recession in late 1979 caused the franchisees to fall far behind in their monthly payments to Miami. Notice of default was sent from Miami to Rudzewicz, who nevertheless continued to operate the restaurant as a Burger King franchise. Burger King sued in federal district court for the southern district of Florida. Rudzewicz contested the court’s personal jurisdiction over him, since he had never been to Florida.

The federal court looked to Florida’s long arm statute and held that it did have personal jurisdiction over the non-resident franchisees, and awarded Burger King a quarter of a million dollars in contract damages and enjoined the franchisees from further operation of the Drayton Plains facility. Franchisees appealed to the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals and won a reversal based on lack of personal jurisdiction. Burger King petitioned the Supreme Ct. for a writ of certiorari.

Justice Brennan delivered the opinion of the court.

The Due Process Clause protects an individual’s liberty interest in not being subject to the binding judgments of a forum with which he has established no meaningful “contacts, ties, or relations.” International Shoe Co. v. Washington. By requiring that individuals have “fair warning that a particular activity may subject [them] to the jurisdiction of a foreign sovereign,” the Due Process Clause “gives a degree of predictability to the legal system that allows potential defendants to structure their primary conduct with some minimum assurance as to where that conduct will and will not render them liable to suit.”…

Where a forum seeks to assert specific jurisdiction over an out-of-state defendant who has not consented to suit there, this “fair warning” requirement is satisfied if the defendant has “purposefully directed” his activities at residents of the forum, and the litigation results from alleged injuries that “arise out of or relate to” those activities, Thus “[t]he forum State does not exceed its powers under the Due Process Clause if it asserts personal jurisdiction over a corporation that delivers its products into the stream of commerce with the expectation that they will be purchased by consumers in the forum State” and those products subsequently injure forum consumers. Similarly, a publisher who distributes magazines in a distant State may fairly be held accountable in that forum for damages resulting there from an allegedly defamatory story.…

…[T]he constitutional touchstone remains whether the defendant purposefully established “minimum contacts” in the forum State.…In defining when it is that a potential defendant should “reasonably anticipate” out-of-state litigation, the Court frequently has drawn from the reasoning of Hanson v. Denckla, 357 U.S. 235, 253 (1958):

The unilateral activity of those who claim some relationship with a nonresident defendant cannot satisfy the requirement of contact with the forum State. The application of that rule will vary with the quality and nature of the defendant’s activity, but it is essential in each case that there be some act by which the defendant purposefully avails itself of the privilege of conducting activities within the forum State, thus invoking the benefits and protections of its laws.

This “purposeful availment” requirement ensures that a defendant will not be hauled into a jurisdiction solely as a result of “random,” “fortuitous,” or “attenuated” contacts, or of the “unilateral activity of another party or a third person,” [Citations] Jurisdiction is proper, however, where the contacts proximately result from actions by the defendant himself that create a “substantial connection” with the forum State. [Citations] Thus where the defendant “deliberately” has engaged in significant activities within a State, or has created “continuing obligations” between himself and residents of the forum, he manifestly has availed himself of the privilege of conducting business there, and because his activities are shielded by “the benefits and protections” of the forum’s laws it is presumptively not unreasonable to require him to submit to the burdens of litigation in that forum as well.

Jurisdiction in these circumstances may not be avoided merely because the defendant did not physically enter the forum State. Although territorial presence frequently will enhance a potential defendant’s affiliation with a State and reinforce the reasonable foreseeability of suit there, it is an inescapable fact of modern commercial life that a substantial amount of business is transacted solely by mail and wire communications across state lines, thus obviating the need for physical presence within a State in which business is conducted. So long as a commercial actor’s efforts are “purposefully directed” toward residents of another State, we have consistently rejected the notion that an absence of physical contacts can defeat personal jurisdiction there.

Once it has been decided that a defendant purposefully established minimum contacts within the forum State, these contacts may be considered in light of other factors to determine whether the assertion of personal jurisdiction would comport with “fair play and substantial justice.” International Shoe Co. v. Washington, 326 U.S., at 320. Thus courts in “appropriate case[s]” may evaluate “the burden on the defendant,” “the forum State’s interest in adjudicating the dispute,” “the plaintiff’s interest in obtaining convenient and effective relief,” “the interstate judicial system’s interest in obtaining the most efficient resolution of controversies,” and the “shared interest of the several States in furthering fundamental substantive social policies.” These considerations sometimes serve to establish the reasonableness of jurisdiction upon a lesser showing of minimum contacts than would otherwise be required. [Citations] Applying these principles to the case at hand, we believe there is substantial record evidence supporting the District Court’s conclusion that the assertion of personal jurisdiction over Rudzewicz in Florida for the alleged breach of his franchise agreement did not offend due process.…

In this case, no physical ties to Florida can be attributed to Rudzewicz other than MacShara’s brief training course in Miami. Rudzewicz did not maintain offices in Florida and, for all that appears from the record, has never even visited there. Yet this franchise dispute grew directly out of “a contract which had a substantial connection with that State.” Eschewing the option of operating an independent local enterprise, Rudzewicz deliberately “reach[ed] out beyond” Michigan and negotiated with a Florida corporation for the purchase of a long-term franchise and the manifold benefits that would derive from affiliation with a nationwide organization. Upon approval, he entered into a carefully structured 20-year relationship that envisioned continuing and wide-reaching contacts with Burger King in Florida. In light of Rudzewicz’ voluntary acceptance of the long-term and exacting regulation of his business from Burger King’s Miami headquarters, the “quality and nature” of his relationship to the company in Florida can in no sense be viewed as “random,” “fortuitous,” or “attenuated.” Rudzewicz’ refusal to make the contractually required payments in Miami, and his continued use of Burger King’s trademarks and confidential business information after his termination, caused foreseeable injuries to the corporation in Florida. For these reasons it was, at the very least, presumptively reasonable for Rudzewicz to be called to account there for such injuries.

…Because Rudzewicz established a substantial and continuing relationship with Burger King’s Miami headquarters, received fair notice from the contract documents and the course of dealing that he might be subject to suit in Florida, and has failed to demonstrate how jurisdiction in that forum would otherwise be fundamentally unfair, we conclude that the District Court’s exercise of jurisdiction pursuant to Fla. Stat. 48.193(1)(g) (Supp. 1984) did not offend due process. The judgment of the Court of Appeals is accordingly reversed, and the case is remanded for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

It is so ordered.

Case questions

- Why did Burger King sue in Florida rather than in Michigan?

- If Florida has a long-arm statute that tells Florida courts that it may exercise personal jurisdiction over someone like Rudzewicz, why is the court talking about the due process clause?

- Why is this case in federal court rather than in a Florida state court?

- If this case had been filed in state court in Florida, would Rudzewicz be required to come to Florida? Explain.

In rem Jurisdiction

In rem jurisdiction, also known as "jurisdiction over the thing," refers to a court's authority to make decisions and rulings concerning a specific property or asset, rather than over a particular individual. This type of jurisdiction is often invoked when the case involves rights or claims associated with a piece of property, such as real estate, personal property, or other assets. In cases involving in rem jurisdiction, the court's authority is based on its control over the property itself, rather than the parties involved. This means that the court can make determinations about the property's ownership, title, rights, or other legal issues related to the property. In rem jurisdiction is commonly used in cases involving property disputes, foreclosure proceedings, probate matters, and admiralty and maritime law.

2.5 Venue

Before concluding the discussion about jurisdiction, we should explore the requirement of venue. Venue refers to the specific geographic location or district where a legal case is heard or tried. It determines the appropriate court within a particular jurisdiction that has the authority to handle a case. While jurisdiction refers to the court's authority to hear a case based on factors such as subject matter and parties involved, venue determines the physical location of the court where the case should be heard. The concept of venue is crucial for ensuring that legal proceedings take place in a fair and convenient location, often to facilitate access to justice for the parties involved and to promote efficiency in the legal process. For example, in a civil lawsuit, venue may be determined based on factors such as where the events giving rise to the dispute occurred, where the parties reside, or where the contract was executed. In New Jersey, the venue of a case filed in the state court system would be the specific county in which the case is filed (e.g. Hunterdon County). If there are concerns about improper venue, parties may seek a change of venue to move the case to a different court location within the same jurisdiction that is a more appropriate geographic location where the case should be heard.

2.6 How a Case Proceeds in Court

In this section, we consider how lawsuits are begun and how they make their way through the Courts. Courts do not reach out for cases. Instead, cases are brought to them, usually when an attorney files a case with the right court on behalf of a person that believes they have suffered a legal harm. Once correctly filed, the case will proceed through the various processes designed with due process concerns in mind. In the United States, we have an adversarial court process, which means that the parties oppose each other throughout the litigation, with the goal of “winning” their case. The lawyer, if one is employed by the litigant, serves as an advocate for the client’s claim. Their duty would be to shape the evidence and the argument—the line of reasoning about the evidence—to advance his client’s cause and persuade the court of its rightness. The lawyer for the opposing party will be doing the same thing, of course, for her client. The judge (or, if one is sitting, the jury) must sort out the facts and reach a decision from this cross-fire of evidence and argument. The litigant that initiated the case has the burden of proof, which in a civil trial is generally a “preponderance of the evidence” which means that the plaintiff’s evidence must outweigh whatever evidence the defendant can muster that casts doubts on the plaintiff’s claim. Let’s review the process in more depth below.

Initial Pleadings and Process

Complaint and Summons

Beginning a lawsuit is simple and is spelled out in the rules of procedure by which each court system operates. A civil plaintiff begins a lawsuit by filing a complaint—a document clearly explaining the grounds for suit—with the clerk of the court. A complaint will have several key components as it serves as an initial pleading and sets the stage for the remainder of the litigation. The complaint will have a caption which indicates the parties to the lawsuit, the court the case is filed in, and the type of case, as well as identifying information called a docket number so the case can be tracked. The complaint must establish that the court has jurisdiction to decide the controversy, and the complaint must state the nature of the plaintiff’s claim and the relief that is being asked for (usually an award of money, but sometimes an injunction, or a declaration of legal rights). In addition, the complaint is signed, attesting to its truthfulness. Once the complaint is filed with the court, the defendant must be served with the complaint and summons. The summons is a court document stating the name of the plaintiff and their attorney and directing the defendant to respond to the complaint within a fixed time period.

Jurisdiction and Venue

As the complaint must establish that the Court has the power to decide the case, the complaint must be filed in a correct location. The Court must have subject matter jurisdiction over the claim in the complaint, and the complaint must be filed in the proper geographic location – called venue.

Service of Process

As stated above, the defendant in the case must be “served”—that is, must receive notice that he has been sued. This delivery of notice is referred to as service of process. Service can be done by physically presenting the defendant with a copy of the summons and complaint. But sometimes the defendant is difficult to find (or deliberately avoids the marshal or other process server). The rules spell out a variety of ways by which individuals and corporations can be served. These include using U.S. Postal Service certified mail or serving someone already designated to receive service of process. A corporation or partnership, for example, is often required by state law to designate a “registered agent” for purposes of getting public notices or receiving a summons and complaint.

Timing of Filing

The timing of the filing is important. Almost every possible legal complaint is governed by a federal or state statute of limitations, which requires a lawsuit to be filed within a certain period of time. For example, in many states a lawsuit for injuries resulting from an automobile accident must be filed within two years of the accident or the plaintiff forfeits his right to proceed. As noted earlier, making a correct initial filing, and including the required components of a complaint in a court that has subject matter jurisdiction is critical to avoiding statute of limitations problems.

Answer and Affirmative Defenses

Once a complaint is appropriately served, the Defendant in a lawsuit files an answer. The answer is the initial pleading of the defendant that is a written response to the plaintiff's claims. The answer typically either ‘admits’ or ‘denies’ the allegations made by the plaintiff. Admitted allegations are accepted as true, while denied allegations require the plaintiff to prove their case. Therefore, most allegations are denied. The answer may also include "affirmative defenses," which are legal reasons that, if proven, would excuse the defendant from liability. Affirmative defenses can also introduce new facts or principles to justify the defendant's actions. As an example, the issue of the statute of limitations, referenced above, could be an affirmative defense if by defendant’s calculations the plaintiff did not file their complaint in time. The answer may also include counterclaims against the plaintiff or cross-claims against other defendants. The answer is filed within a specific time frame governed by the rules of the court in which the complaint was filed.

Motions and Discovery

The early phases of a civil action are characterized by many different kinds of motions and the exchange of mutual fact-finding between the parties that is known as discovery. After the pleadings, the parties may make various motions, which are requests to the judge to rule on legal issues in the case. Motions in the early stages of a lawsuit usually aim to dismiss the lawsuit, to have it moved to another venue, or to compel the other party to act in certain ways during the discovery process.

Motions

In litigation, a "motion" is a formal request made by one party to a lawsuit (the moving party) asking the court to take a specific action or make a particular decision. If a party wins a motion, or loses one for that matter, it can streamline the legal issues in the case substantially.

Motions to Dismiss at Pleadings Stage

A complaint and subsequent pleadings are usually quite general and give little detail. But in some instances, a case can be decided based on the pleadings alone. For example, if the defendant fails to answer the complaint, the Plaintiff can move for the court to enter a default judgment, awarding the plaintiff what they seek.

A defendant that believes that the complaint is defective can move to dismiss the complaint on the grounds that the plaintiff failed to “state a claim on which relief can be granted,” or on the basis that there is no subject matter jurisdiction for the court chosen by the plaintiff, or on the basis that there is no personal jurisdiction over the defendant. The defendant is saying, in effect, that even if all the plaintiff’s allegations are true, they do not amount to a legal claim that can be heard by the court.

Motion for Summary Judgment

A "motion for summary judgment" is a legal request made by a party to a lawsuit, asking the court to decide the case or specific claims in their favor without going to trial. This motion is typically filed after the parties have conducted discovery (summarized below) such that key facts in the case are known to both parties. If there is no triable question of fact or law, there is no reason to have a trial with a jury, and a judge could simply decide the case.

Discovery

If the claim made by the plaintiff involves a factual dispute, the case will usually involve some degree of discovery, where each party tries to get as much information out of the other party as the discovery rules allow. In a civil action, the parties are entitled to learn the facts of the case before trial. The basic idea is to help the parties determine what the evidence might be, who the potential witnesses are, and what specific issues are relevant. Full discovery helps determine which cases should genuinely go to trial to be heard by a jury, and which cases can be amicably settled. It helps each side understand the strengths and weaknesses of their opponent's claims and defenses. There are several methods by which discovery can take place, the most common of which are listed here:

Interrogatories: Written questions that one party sends to the other which the recipient is required to answer under oath. Interrogatories seek factual information, legal contentions, or details about the parties' claims and defenses.

Depositions: Oral testimony given under oath outside of court, typically recorded by a court reporter. Parties or witnesses answer questions posed by attorneys. Depositions help gather firsthand accounts and allow each party to assess credibility.

Requests for Production: Formal requests for specific documents, electronically stored information, or tangible items relevant to the case. These requests seek evidence such as contracts, emails, reports, and records.

Requests for Admission: Written requests asking the opposing party to admit or deny specific statements or facts. Admissions streamline the issues by eliminating the need to prove certain facts at trial. An allegation that was denied in the pleading stage of the lawsuit might now be admitted after full discovery.

Physical and Mental Examinations: When a person's physical or mental condition is relevant to the case, such as in a personal injury case, a court may order an examination by a qualified medical professional.

The lawyers, not the court, run the discovery process. For example, one party simply makes a written demand, stating the time at which the deposition will take place or the type of documents it wishes to inspect and make copies of. A party unreasonably resisting discovery methods (whether depositions, written interrogatories, or requests for documents) can be challenged using a motion to compel discovery as judges can be brought into the process to push reluctant parties to make more disclosure or to protect a party from irrelevant or unreasonable discovery requests. For example, the party receiving the discovery request can apply to the court for a protective order if it can show that the demand is for privileged material (e.g., a party’s lawyers’ records are not open for inspection) or that the demand was made to harass the opponent. In complex cases between companies, the discovery of documents can run into tens of millions of pages and can take years. Depositions can consume days or even weeks of an executive’s time.

The Pretrial and Trial Phase

Once the discovery period is complete, the case moves on to trial if it has not been settled. Most cases are settled before this stage; perhaps 85 percent of all civil cases end before trial, and more than 90 percent of criminal prosecutions end with a guilty plea.

Pretrial Conference

Depending on the nature and complexity of the case, the court may hold a pretrial conference to clarify the issues and establish a timetable for the upcoming trial, as well as discuss any legal issues or pretrial motions raised in the case. The pretrial conference may also be used as a settlement conference to see if the parties can work out their differences and avoid trial altogether. If the judge believes that settlement is a possibility, the judge will explore the strengths and weaknesses of each party’s case with the attorneys. The parties may decide that it is more prudent or efficient to settle than to risk going to trial.

Trial

If the case does not settle, motions have been fully litigated, and discovery is complete, the case will be scheduled for trial.

Jury Selection

At trial, the first order of business is to select a jury. The judge and sometimes the lawyers are permitted to question the jurors to be sure that they are unbiased. This questioning is known as the voir dire (pronounced vwahr-DEER). This is an important process, and a great deal of thought goes into selecting the jury, especially in high-profile cases. A jury panel can be as few as six persons, or as many as twelve, with alternates selected and sitting in court in case one of the jurors is unable to continue. In a long trial, having alternates is essential; even in shorter trials, most courts will have at least two alternate jurors.

In both criminal and civil trials, each side has opportunities to challenge potential jurors for cause. For example, in the Robinsons’ case against Audi, the attorneys representing Audi will want to know if any prospective jurors have ever owned an Audi, what their experience has been, and if they had a similar problem (or worse) with their Audi that was not resolved to their satisfaction. If so, the defense attorney could well believe that such a juror has a potential for a bias against her client. In that case, she could use a for cause challenge, explaining to the judge the basis for her challenge. The judge, at her discretion, could either accept the for-cause reason or reject it.

Even if an attorney cannot articulate a for-cause reason acceptable to the judge, she may use one of several peremptory challenges that most states (and the federal system) allow. A trial attorney with many years of experience may have a sixth sense about a potential juror and, in consultation with the client, may decide to use a peremptory challenge to avoid having that juror on the panel.

Opening Statements

After the jury is sworn and seated, the plaintiff’s lawyer makes an opening statement, laying out the nature of the plaintiff’s claim, the facts of the case as the plaintiff sees them, and the evidence that the lawyer will present. The defendant’s lawyer may also make an opening statement or may reserve his right to do so at the end of the plaintiff’s case.

Examination of Witnesses

Once opening statements are completed, the plaintiff’s lawyer then calls witnesses and presents the physical evidence that is relevant to her proof, called the plaintiff's case in chief. The initial questioning of witnesses by the party that calls them to the stand is a direct examination. Testimony at trial is usually far from a smooth narration. The rules of evidence (that govern the kinds of testimony and documents that may be introduced at trial) and the question-and-answer format tend to make the presentation of evidence choppy and difficult to follow.

Anyone who has watched an actual televised trial or a television melodrama featuring a trial scene will appreciate the nature of the trial itself: witnesses are asked questions about a number of issues that may or may not be related, the opposing lawyer will frequently object to the question or the form in which it is asked, and the jury may be sent from the room while the lawyers argue at the bench before the judge.

After direct examination of each witness is over, the opposing lawyer may conduct cross-examination. The formal rules of direct testimony are then relaxed, and the cross-examiner may probe the witness more informally, asking questions that may not seem immediately relevant. The opposing attorney may become harsh trying to cast doubt on a witness’s credibility, trying to trip her up and show that the answers she gave are false or not to be trusted. This use of cross-examination, along with the requirement that the witness must respond to questions that are at all relevant to the questions raised by the case, distinguishes common-law courts from those of authoritarian regimes around the world.

Following cross-examination, the plaintiff’s lawyer may then question the witness again: this is called redirect examination and is used to demonstrate that the witness’s original answers were accurate and to show that any implications otherwise, suggested by the cross-examiner, were unwarranted. The cross-examiner may then engage the witness in recross-examination, and so on. The process usually stops after cross-examination or redirect.

During the trial, the judge’s chief responsibility is to see that the trial is fair to both sides. One big piece of that responsibility is to rule on the admissibility of evidence. A judge may rule that a particular question is out of order—that is, not relevant or appropriate—or that a given document is irrelevant. Where the attorney is convinced that a particular witness, a particular question, or a particular document (or part thereof) is critical to her case, she may preserve an objection to the court’s ruling by saying “exception,” in which case the court stenographer will note the exception, and the attorney may raise these issues on appeal should there be one.

At the end of the plaintiff’s case, the defendant presents his case in chief, following the same procedure just outlined. The plaintiff is then entitled to present rebuttal witnesses, if necessary, to deny or argue with the evidence the defendant has introduced. The defendant in turn may present “surrebuttal” witnesses.

Motion for Directed Verdict

When all testimony has been introduced, either party may ask the judge for a motion for directed verdict—a verdict decided by the judge without advice from the jury. This motion may be granted if the plaintiff has failed to introduce evidence that is legally sufficient to meet her burden of proof or if the defendant has failed to do the same on issues on which she has the burden of proof. (For example, the plaintiff alleges that the defendant owes him money and introduces a signed promissory note. The defendant cannot show that the note is invalid. The defendant must lose the case unless he can show that the debt has been paid or otherwise discharged.)

The defendant can move for a directed verdict at the close of the plaintiff’s case, but the judge will usually wait to hear the entire case until deciding whether to do so. Directed verdicts are not usually granted, since it is the jury’s job to determine the facts in dispute.

Closing Argument

If the judge refuses to grant a directed verdict, each lawyer will then present a closing argument to the jury (or, if there is no jury, to the judge alone). The closing argument is used to tie up the loose ends, as the attorney tries to bring together various seemingly unrelated facts into a story that will make sense to the jury, and make the argument as to why finding in their client’s favor is the correct verdict.

Jury Instruction

After closing arguments, the judge will instruct the jury. The purpose of jury instruction is to explain to the jurors the meaning of the law as it relates to the issues they are considering and to tell the jurors what facts they must determine if they are to give a verdict for one party or the other. Each lawyer will have prepared a set of written instructions that she hopes the judge will give to the jury. These will be tailored to advance her client’s case. Many a verdict has been overturned on appeal because a trial judge has wrongly instructed the jury. The judge will carefully determine which instructions to give and often will use a set of pattern instructions provided by the state bar association or the supreme court of the state. These pattern jury instructions are often safer because they are patterned after language that appellate courts have used previously, and appellate courts are less likely to find reversible error in the instructions. In civil cases, the plaintiff has the burden of proof, typically of proving their claim by a preponderance of the evidence. The jury will be instructed on what this means and how to apply this burden of proof.

Deliberations and Verdict

After all instructions are given, the jury will retire to a private room and discuss the case and the answers requested by the judge for as long as it takes to reach a unanimous verdict. In New Jersey, civil cases are not required to be unanimous. Instead, only 5/6 of the jurors need to agree on a verdict. If the jury cannot reach a decision, this is called a hung jury, and the case will have to be retried. When a jury does reach a verdict, it delivers it in court with both parties and their lawyers present. The jury is then discharged, and control over the case returns to the judge. (If there is no jury, the judge will usually announce in a written opinion his findings of fact and how the law applies to those facts. Juries just announce their verdicts and do not state their reasons for reaching them.)

Posttrial Motions

Once the trial is complete, it is still possible to ask the judge to make a ruling that is contrary to the jury verdict. The losing party at trial is allowed to ask the judge for a new trial or for a judgment notwithstanding the verdict (often called a JNOV, from the Latin non obstante veredicto).

Motion for a New Trial: A motion for a new trial is a request made by a party after a trial has concluded, asking the court to set aside the jury's verdict and order a new trial. This motion is typically based on perceived errors or irregularities that occurred during the trial that may have influenced the outcome. The party seeking a new trial asserts that some legal error, procedural mistake, or unfairness occurred during the trial process that warrants another opportunity to present their case.

Judgment Notwithstanding the Verdict (JNOV): A JNOV is a motion that challenges the jury's verdict after trial. It is typically filed by the losing party, arguing that the jury's verdict was not supported by sufficient evidence or was legally erroneous. In other words, the party contends that even if all the evidence is viewed in the light most favorable to the winning party, no reasonable jury could have reached the verdict that was reached.

Post-trial, a party may renew a prior motion for directed verdict. A judge who decides that a directed verdict is appropriate will usually wait to see what the jury’s verdict is. If it is favorable to the party the judge thinks should win, she can rely on that verdict. If the verdict is for the other party, the judge can grant the motion for JNOV. This is a safer way to proceed because if the judge is reversed on appeal, a new trial is not necessary. The jury’s verdict always can be restored, whereas without a jury verdict (as happens when a directed verdict is granted before the case goes to the jury), the entire case must be presented to a new jury.

Case 2.2

Ferlito v. Johnson & Johnson Products, Inc., 771 F. Supp. 196 (U.S. District Ct., Eastern District of Michigan 1991)

GADOLA, J.

Plaintiffs Susan and Frank Ferlito, husband and wife, attended a Halloween party in 1984 dressed as Mary (Mrs. Ferlito) and her little lamb (Mr. Ferlito). Mrs. Ferlito had constructed a lamb costume for her husband by gluing cotton batting manufactured by defendant Johnson & Johnson Products (“JJP”) to a suit of long underwear. She had also used defendant’s product to fashion a headpiece, complete with ears. The costume covered Mr. Ferlito from his head to his ankles, except for his face and hands, which were blackened with Halloween paint. At the party Mr. Ferlito attempted to light his cigarette by using a butane lighter. The flame passed close to his left arm, and the cotton batting on his left sleeve ignited. Plaintiffs sued defendant for injuries they suffered from burns which covered approximately one-third of Mr. Ferlito’s body.

Following a jury verdict entered for plaintiffs November 2, 1989, the Honorable Ralph M. Freeman entered a judgment for plaintiff Frank Ferlito in the amount of $555,000 and for plaintiff Susan Ferlito in the amount of $ 70,000. Judgment was entered November 7, 1989. Subsequently, on November 16, 1989, defendant JJP filed a timely motion for judgment notwithstanding the verdict pursuant to Fed.R.Civ.P. 50(b) or, in the alternative, for new trial. Plaintiffs filed their response to defendant’s motion December 18, 1989; and defendant filed a reply January 4, 1990. Before reaching a decision on this motion, Judge Freeman died. The case was reassigned to this court April 12, 1990.

MOTION FOR JUDGMENT NOTWITHSTANDING THE VERDICT

Defendant JJP filed two motions for a directed verdict, the first on October 27, 1989, at the close of plaintiffs’ proofs, and the second on October 30, 1989, at the close of defendant’s proofs. Judge Freeman denied both motions without prejudice. Judgment for plaintiffs was entered November 7, 1989; and defendant’s instant motion, filed November 16, 1989, was filed in a timely manner.

The standard for determining whether to grant a j.n.o.v. is identical to the standard for evaluating a motion for directed verdict:

In determining whether the evidence is sufficient, the trial court may neither weigh the evidence, pass on the credibility of witnesses nor substitute its judgment for that of the jury. Rather, the evidence must be viewed in the light most favorable to the party against whom the motion is made, drawing from that evidence all reasonable inferences in his favor. If after reviewing the evidence…the trial court is of the opinion that reasonable minds could not come to the result reached by the jury, then the motion for j.n.o.v. should be granted.

To recover in a “failure to warn” product liability action, a plaintiff must prove each of the following four elements of negligence: (1) that the defendant owed a duty to the plaintiff, (2) that the defendant violated that duty, (3) that the defendant’s breach of that duty was a proximate cause of the damages suffered by the plaintiff, and (4) that the plaintiff suffered damages.

To establish a prima facie case that a manufacturer’s breach of its duty to warn was a proximate cause of an injury sustained, a plaintiff must present evidence that the product would have been used differently had the proffered warnings been given.1[Citations omitted] In the absence of evidence that a warning would have prevented the harm complained of by altering the plaintiff’s conduct, the failure to warn cannot be deemed a proximate cause of the plaintiff’s injury as a matter of law. [In accordance with procedure in a diversity of citizenship case, such as this one, the court cites Michigan case law as the basis for its legal interpretation.]

…

A manufacturer has a duty “to warn the purchasers or users of its product about dangers associated with intended use.” Conversely, a manufacturer has no duty to warn of a danger arising from an unforeseeable misuse of its product. [Citation] Thus, whether a manufacturer has a duty to warn depends on whether the use of the product and the injury sustained by it are foreseeable. Gootee v. Colt Industries Inc., 712 F.2d 1057, 1065 (6th Cir. 1983); Owens v. Allis-Chalmers Corp., 414 Mich. 413, 425, 326 N.W.2d 372 (1982). Whether a plaintiff’s use of a product is foreseeable is a legal question to be resolved by the court. Trotter, supra. Whether the resulting injury is foreseeable is a question of fact for the jury.2 Thomas v. International Harvester Co., 57 Mich. App. 79, 225 N.W.2d 175 (1974).

In the instant action no reasonable jury could find that JJP’s failure to warn of the flammability of cotton batting was a proximate cause of plaintiffs’ injuries because plaintiffs failed to offer any evidence to establish that a flammability warning on JJP’s cotton batting would have dissuaded them from using the product in the manner that they did.

Plaintiffs repeatedly stated in their response brief that plaintiff Susan Ferlito testified that “she would never again use cotton batting to make a costume…" However, a review of the trial transcript reveals that plaintiff Susan Ferlito never testified that she would never again use cotton batting to make a costume. More importantly, the transcript contains no statement by plaintiff Susan Ferlito that a flammability warning on defendant JJP’s product would have dissuaded her from using the cotton batting to construct the costume in the first place. At oral argument counsel for plaintiffs conceded that there was no testimony during the trial that either plaintiff Susan Ferlito or her husband, plaintiff Frank J. Ferlito, would have acted any different if there had been a flammability warning on the product’s package. The absence of such testimony is fatal to plaintiffs’ case; for without it, plaintiffs have failed to prove proximate cause, one of the essential elements of their negligence claim.

In addition, both plaintiffs testified that they knew that cotton batting burns when it is exposed to flame. Susan Ferlito testified that she knew at the time she purchased the cotton batting that it would burn if exposed to an open flame. Frank Ferlito testified that he knew at the time he appeared at the Halloween party that cotton batting would burn if exposed to an open flame. His additional testimony that he would not have intentionally put a flame to the cotton batting shows that he recognized the risk of injury of which he claims JJP should have warned. Because both plaintiffs were already aware of the danger, a warning by JJP would have been superfluous. Therefore, a reasonable jury could not have found that JJP’s failure to provide a warning was a proximate cause of plaintiffs’ injuries.

The evidence in this case clearly demonstrated that neither the use to which plaintiffs put JJP’s product nor the injuries arising from that use were foreseeable. Susan Ferlito testified that the idea for the costume was hers alone. As described on the product’s package, its intended uses are for cleansing, applying medications, and infant care. Plaintiffs’ showing that the product may be used on occasion in classrooms for decorative purposes failed to demonstrate the foreseeability of an adult male encapsulating himself from head to toe in cotton batting and then lighting up a cigarette.

ORDER

NOW, THEREFORE, IT IS HEREBY ORDERED that defendant JJP’s motion for judgment notwithstanding the verdict is GRANTED.

IT IS FURTHER ORDERED that the judgment entered November 2, 1989, is SET ASIDE.

IT IS FURTHER ORDERED that the clerk will enter a judgment in favor of the defendant JJP.

Case questions

- The opinion focuses on proximate cause. As we will see when we study tort law, a negligence case cannot be won unless the plaintiff shows that the defendant has breached a duty and that the defendant’s breach has actually and proximately caused the damage complained of. What, exactly, is the alleged breach of duty by the defendant here?

- Explain why Judge Gadola reasoning that JJP had no duty to warn in this case. After this case, would they then have a duty to warn, knowing that someone might use their product in this way?

Judgment or Order

At the end of a trial, the judge will enter an order that makes findings of fact (often with the help of a jury) and conclusions of law. The judge will also make a judgment as to what relief or remedy should be given. Often it is an award of money damages to one of the parties. The losing party may ask for a new trial at this point or within a short period of time following. Once the trial judge denies any such request, the judgment—in the form of the court’s order—is final.

Appeal

If the loser’s motion for a new trial or a JNOV is denied, the losing party may appeal but must ordinarily post a bond sufficient to ensure that there are funds to pay the amount awarded to the winning party. In an appeal, the appellant aims to show that there was some prejudicial error committed by the trial judge. There will be errors, of course, but the errors must be significant (i.e., not harmless). The basic idea is for an appellate court to ensure that a reasonably fair trial was provided to both sides. Enforcement of the court’s judgment—an award of money, an injunction—is usually stayed (postponed) until the appellate court has ruled. As noted earlier, the party making the appeal is called the appellant, and the party defending the judgment is the appellee (or in some courts, the petitioner and the respondent).

During the trial, the losing party may have objected to certain procedural decisions by the judge. In compiling a record on appeal, the appellant needs to show the appellate court some examples of mistakes made by the judge—for example, having erroneously admitted evidence, having failed to admit proper evidence that should have been admitted, or having wrongly instructed the jury. The appellate court must determine if those mistakes were serious enough to amount to prejudicial error.

Appellate and trial procedures are different. The appellate court does not hear witnesses or accept evidence. It reviews the record of the case—the transcript of the witnesses’ testimony and the documents received into evidence at trial—to try to find a legal error on a specific request of one or both of the parties. The parties’ lawyers prepare briefs (written statements containing the facts in the case), the procedural steps taken, and the argument or discussion of the meaning of the law and how it applies to the facts. After reading the briefs on appeal, the appellate court may dispose of the appeal without argument, issuing a written opinion that may be very short or many pages. Often, though, the appellate court will hear oral argument. (This can be months, or even more than a year after the briefs are filed.) Each lawyer is given a short period of time, usually no more than thirty minutes, to present his client’s case. The lawyer rarely gets a chance for an extended statement because he is usually interrupted by questions from the judges. Through this exchange between judges and lawyers, specific legal positions can be tested and their limits explored.

Depending on what it decides, the appellate court will affirm the lower court’s judgment, modify it, reverse it, or remand it to the lower court for retrial or other action directed by the higher court. The appellate court itself does not take specific action in the case; it sits only to rule on contested issues of law. The lower court must issue the final judgment in the case. As we have already seen, there is the possibility of appealing from an intermediate appellate court to the state supreme court in twenty-nine states and to the U.S. Supreme Court from a ruling from a federal circuit court of appeal. In cases raising constitutional issues, there is also the possibility of appeal to the Supreme Court from the state courts.

Like trial judges, appellate judges must follow previous decisions, or precedent. But not every previous case is a precedent for every court. Lower courts must respect appellate court decisions, and courts in one state are not bound by decisions of courts in other states. State courts are not bound by decisions of federal courts, except on points of federal law that come from federal courts within the state or from a federal circuit in which the state court sits. A state supreme court is not bound by case law in any other state. But a supreme court in one state with a type of case it has not previously dealt with may find persuasive reasoning in decisions of other state supreme courts.