Chapter 3 – Alternative Dispute Resolution

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe the process of negotiation as it is commonly employed in business.

- Discuss the process of mediation as an alternative dispute resolution (ADR) strategy.

- Discuss the option of arbitration as an alternative dispute resolution (ADR) strategy.

- Describe the benefits and drawbacks of ADR as compared to litigation.

3.1 General Perspectives on Alternative Dispute Resolution

Imagine that you believe you’ve been wronged by a supplier, by your employer, or by a business where you are a customer. You’ve correctly determined that you have an actionable legal claim. But, now what do you do to try to resolve that claim? We learned in a prior chapter that one option might be to initiate a lawsuit against the alleged wrongdoer. But you know that litigation is expensive and time consuming, not to mention frustrating. If you want to try to continue to have a relationship with a supplier, employer, or other business, filing a lawsuit against them is unlikely to promote a strong current and future business relationship. If the matter is of a private nature you may not want to engage in a public process to determine the outcome. So, while you want the matter to be addressed and resolved, you may not want to engage in public, time-consuming, expensive and adversarial litigation to resolve it.

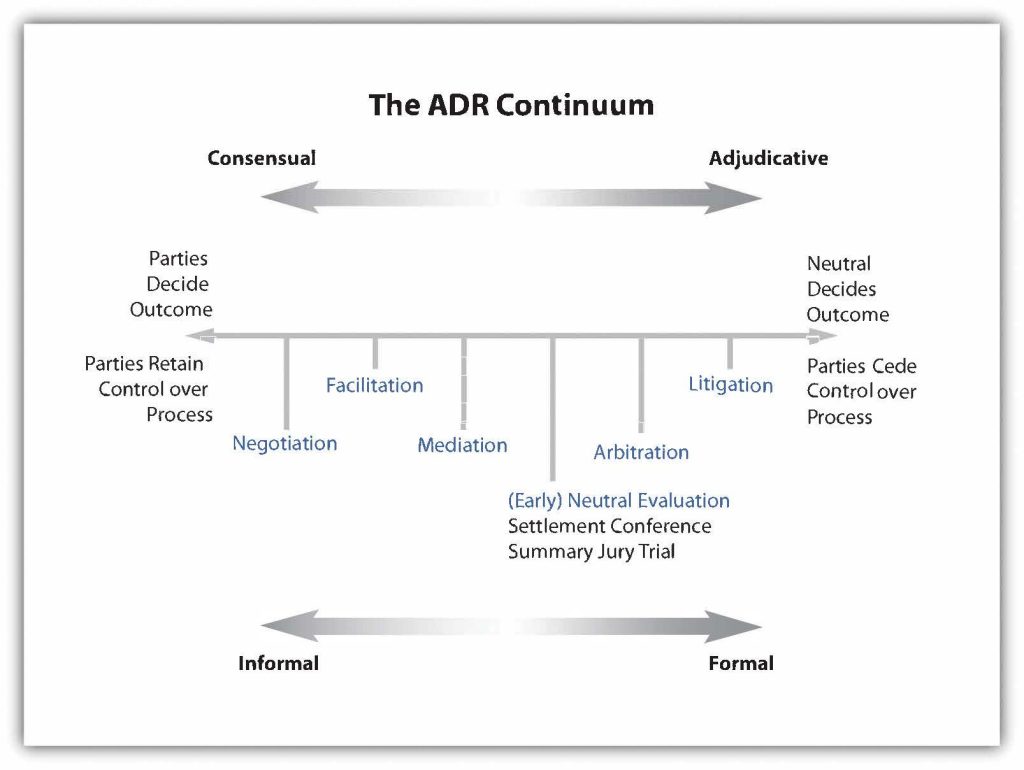

A common method of dispute resolution that avoids many of the challenges associated with litigation is alternative dispute resolution. Alternative dispute resolution (ADR) is a term that encompasses many different methods of dispute resolution other than litigation. ADR involves resolving disputes outside of the judicial process, though the judiciary can require parties to participate in specific types of ADR, such as arbitration, for some types of conflicts. Moreover, some ADR methods vest the power to resolve the dispute in a neutral party, while other strategies vest that power in the parties themselves. See Figure 3.1 “A Continuum of Different ADR Methods” to understand ADR methods based on where the power to solve the dispute is vested.

Figure 3.1 A Continuum of Different ADR Methods

Source: Adapted from New York State Unified Court System

Common methods of ADR include negotiation, mediation, and arbitration. Less frequently used methods of ADR include minitrials, hybrid forms of mediation-arbitration (with elements of both), and collaborative goal-oriented processes. ADR is often used to resolve disputes between businesses, employers and employees, and businesses and consumers. ADR can also be used in many other types of conflicts. For instance, ADR strategies can be used in domestic law cases, such as divorce, or in international legal issues, such as issues relating to transboundary pollution. This Chapter focuses on the use of common ADR methods in business, including the benefits and drawbacks to each. We will also examine potential consequences to parties that have unequal bargaining power. Additionally, we will examine the use of ADR methods in situations where ADR may not be the most appropriate method of dispute resolution, such as civil rights violations.

ADR methods are used outside of the courtroom, but that does not mean that they are outside of the interests of our legal system. Participation in ADR has important legal consequences. For instance, parties that have agreed by contract to be subject to binding arbitration give up their constitutional right to bring their complaint to court. The Federal Arbitration Act (FAA) is a federal statute under which parties are required to participate in arbitration when they have agreed by contract to do so, even in state court matters. Indeed, the FAA is a national policy favoring arbitration. In New Jersey, there are certain types of cases filed with courts that are required to go first to mandatory arbitration. This court-ordered arbitration would be non-binding because it was ordered by a court, yet this court rule showcases the policy of the state to try to use ADR to resolve disputes between parties.

It is likely that you will or already have agreed to a contract that contains a mandatory arbitration clause. Arbitration clauses are common in business contracts, consumer contracts, and even employee handbooks. If a dispute arises under that contract or agreement, you will be required to arbitrate your claim rather than going straight to court. Under a binding arbitration clause, you will have waived your constitutional rights to go to court. Because of this, it’s important to understand the ADR process, situations in which litigation is a better choice than ADR, and special issues that arise when parties have unequal bargaining power.

3.2 Negotiation

Let’s start this section with an example. A tent manufacturer has a supplier of tent fabric that supplies an appropriate water-resistant fabric to construct the tents. After many years of a good working relationship, there is an issue with the fabric supplier. Specifically, the fabric delivered was not water-resistant, despite the necessity of water-resistant fabric to produce the tents. The tent manufacturer notifies the supplier of the problem and the supplier denies that there is any issue with the fabric sent to fulfill the order. The tent manufacturer refuses to pay for the fabric. The supplier insists on payment before any future delivery of additional fabric. Without water-resistant fabric, the manufacturer cannot continue to produce tents.

This is an example of a business-to-business (B2B) dispute. Despite the problem, the manufacturer will likely want to continue working with the supplier and preserve a good, long-standing relationship. Accordingly, the parties will probably want to resolve this dispute quickly and without hard feelings. If this is the goal of the parties, it is unlikely that either one will immediately hire an attorney to file a formal complaint. That does not change the fact that there is a dispute that needs to be resolved.

One of the first strategies that the manufacturer and supplier are likely to employ is negotiation. Negotiation is a method of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) that retains power to resolve the dispute to the parties involved. No outside third party is vested with authoritative decision-making power concerning the resolution of the dispute. Negotiation requires the parties to define the conflicts and agree to an outcome to resolve those conflicts. Often, this can take the form of a compromise. Note that a compromise does not mean that anyone “loses.” Indeed, if both parties are satisfied with the result of the negotiation and the business relationship can continue moving forward, then both parties will be very likely to consider this as a “winning” situation.

Benefits to negotiation as a method of ADR include its potential for a speedy resolution, the inexpensive nature of participation, and the fact that parties participate voluntarily. Drawbacks include the fact that there are no set rules, and either party may bargain badly or even unethically, if they choose to do so. In a negotiation, there is no neutral party charged with ensuring that rules are followed, that the negotiation strategy is fair, or that the overall outcome is sound. Moreover, any party can walk away from the negotiation whenever it wishes, even going on to pursue another method of dispute resolution as appropriate. Negotiation is not guaranteed to resolve the dispute.

Generally speaking, attorneys are not involved in many business negotiations. Attorneys are not prohibited from being negotiators, or providing legal advice to a party that is negotiating, but they are not required to have a successful negotiation. Some parties might find it helpful not to have attorneys get involved when they feel capable of handling the negotiation themselves. Whether attorneys get involved, therefore, will depend on the circumstances of the negotiation.

Though the example above is a B2B dispute, the parties may or may not have equal bargaining power. If the manufacturer and the supplier are both dependent on each other for roughly equal portions of the respective businesses, then they are most likely relatively equal with respect to bargaining power. But if the manufacturer is a very small business but the supplier is a very large fabric company, then the B2B negotiation is potentially unbalanced, since one party has a much more powerful bargaining position than the other. For example, if the business needs that particular type of fabric, which is only available from one supplier, but the supplier doesn’t need the relationship with the tent business, this would result in unequal bargaining power.

When the negotiation occurs as a result of a dispute, then the party with the weakest bargaining position may be in a vulnerable spot. While anyone can engage in negotiation, this is a skill developed by people who are charged with settling existing disputes or with creating new agreements. The goal of negotiation is to achieve a “win-win” outcome, unlike litigation where one party must win and the other lose. The book Getting to Yes by Harvard Program on Negotiation members emphasizes principled negotiation and provides steps and strategies for achieving this goal. Common concepts in negotiation include BATNA (best alternative to a negotiated agreement), WATNA (worst alternative to a negotiated agreement), bargaining zone (the area within which parties can find an acceptable agreement), and reservation point (a party’s “bottom line” beyond which it will not agree to terms). This is just one strategy for negotiation.

Going back to the example, imagine that after negotiating with the fabric supplier, the tent manufacturer learns that the fabric supplier believed that it sent the correct fabric as a new tent employee inadvertently ordered the wrong fabric. Business records then confirm this was the source of the error. This sort of misunderstanding should be cleared up through negotiation. Any number of outcomes are now available to the parties once they’ve identified the source of the problem. It is likely that the dispute can be resolved in a professional manner, and the working relationship between the two businesses can be preserved.

3.3 Mediation

Mediation is a method of ADR in which parties work to form a mutually acceptable agreement. Like negotiation, parties in mediation do not vest authority to decide the dispute in a neutral third party. Instead, this authority to settle the dispute remains with the parties themselves, who are free to terminate mediation if they believe it is not working. Mediation is appropriate only for parties who are willing to participate in the process. Like negotiation, mediation seeks a “win-win” outcome for the parties involved. Additionally, mediation is confidential, which can be an attractive attribute for people who wish to avoid the public nature of litigation. The mediation process is usually much faster than litigation, and the associated costs can be substantially less expensive than litigation. If the dispute is unable to be resolved through mediation, the parties are free to pursue another form of ADR, such as arbitration, or they choose to litigate their claims in court.

A neutral third-party mediator is crucial to the mediation process. Mediators act as a go-between for the parties, seeking to facilitate the agreement. Requirements to be a mediator vary by state. There are no uniform licensing requirements, but some states require specific training or qualifications for a person to be certified as a mediator. Mediators do not provide advice on the subject matter of the dispute. In fact, the mediators may not possess any subject-matter expertise concerning the nature of the dispute. However, many mediators are trained in conflict resolution, and this allows them to employ methods to discover common goals or objectives, set aside issues that are not relevant, and facilitate an agreement into which the parties will voluntarily enter. Mediators try to find common ground by identifying common goals or objectives and by asking parties to set aside the sometimes emotionally laden obstacles that are not relevant to the sought-after agreement itself.

Parties choose their mediator. This choice is often made based on the mediator’s reputation as a skilled conflict resolution expert, professional background, training, experience, cost, and availability. After a mediator is chosen, the parties prepare for mediation. For instance, prior to the mediation process, the mediator typically asks the parties to sign a mediation agreement. This agreement may embody the parties’ commitments to proceed in good faith, understanding of the voluntary nature of the process, commitments to confidentiality, and recognition of the mediator’s role of neutrality rather than one of legal counsel. At the outset, the mediator typically explains the process that the mediation will observe. The parties then proceed according to that plan, which may include opening statements, face-to-face communication, or indirect communication through the mediator. The mediator may suggest options for resolution and, depending on his or her skill, may be able to suggest alternatives not previously considered by the parties.

Mediation is often an option for parties who cannot negotiate with each other but who could reach a mutually beneficial or mutually acceptable resolution with the assistance of a neutral party to help sort out the issues to find a resolution that achieves the parties’ objectives. Sometimes parties in mediation retain attorneys, but this is not required. If parties do retain counsel, the costs for participating in the mediation will obviously increase.

In business, mediation is often the method of ADR used in disputes between employers and employees about topics such as workplace conditions, wrongful discharge, or advancement grievances. Mediation is used in disputes between businesses, such as in contract disputes. Mediation is also used for disputes arising between businesses and consumers, such as in medical malpractice cases or health care disputes.

For example, in the tent fabric dispute, a mediator can assist the parties in communicating their concerns and interests effectively, exploring potential solutions, and reaching a mutually satisfactory agreement. The mediator can first meet with each party separately to gain an understanding of their positions, interests, and concerns. The mediator can then facilitate a joint meeting where the parties can discuss the issue, clarify misunderstandings, and brainstorm potential solutions. The mediator can also help the parties evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of their positions and explore alternative options that may address the needs of both parties. If the core issue in the dispute is whether the fabric was really water-resistant, the mediator could help the parties decide on how to determine the quality of the fabric, say through some sort of testing. If the issue is financial, a mediator could help the parties to discuss and ultimately agree to spreading the cost of a replacement fabric over future orders, or otherwise revise their payment terms or delivery schedule to address the issue.

Like other forms of dispute resolution, mediation has benefits and drawbacks. Benefits are many. They include the relative expediency of reaching a resolution, the reduced costs as compared to litigation, the ability for parties that are unable to communicate with each other to resolve their dispute using a non-adversarial process, the imposition of rules on the process by the mediator to keep parties “within bounds” of the process, confidentiality, and the voluntary nature of participation. Of course, the potential for a “win-win” outcome is a benefit. Attorneys may or may not be involved, and this can be viewed as either a benefit or a drawback, depending on the circumstances.

Drawbacks to mediation also exist. For example, if parties are not willing to participate in the mediation process, the mediation will not work. This is because mediation requires voluntary participation between willing parties to reach a mutually agreeable resolution. Additionally, even after considerable effort by the parties in dispute, the mediation may fail. This means that the resolution of the problem may have to be postponed until another form of ADR is used, or until the parties litigate their case in court. Since mediators are individuals, they have different levels of expertise in conflict resolution, and they possess different backgrounds and worldviews that might influence the manner in which they conduct mediation. Parties may be satisfied with one mediator but not satisfied in subsequent mediations with a different mediator. Even if an agreement is reached, the mediation itself is usually not binding. Parties can later become dissatisfied with the agreement reached during mediation and choose to pursue the dispute through other ADR methods or through litigation. For this reason, parties often enter into a legally binding contract that embodies the terms of the resolution of the mediation immediately on conclusion of the successful mediation. Therefore, the terms of the mediation can become binding if they are reduced to such a contract, and some parties may find this to be disadvantageous to their interests. Of course, any party that signs such an agreement would do so voluntarily. However, in some cases, if legal counsel is not involved, parties may not fully understand the implications of the agreement that they are signing.

3.4 Arbitration

Arbitration is a method of ADR in which parties vest authority in a third-party neutral decision maker who will hear their case and issue a decision, which is called an arbitration award.

An arbitrator presides over arbitration proceedings, much as a judge would preside over a trial. For instance, they determine which evidence can be introduced, hear the parties’ cases, and issue decisions. Arbitrators may even be former members of the judiciary. Often, arbitrators are experts in the law and subject matter at issue in the dispute.

Their decisions do not form binding precedent, so no single arbitration decision would be binding on the next arbitration even if the issue in the dispute was similar. Arbitrators may be certified by the state in which they arbitrate, and they may arbitrate only certain types of claims. For instance, the Better Business Bureau trains its own arbitrators to hear common complaints between businesses and consumers (B2C).

Sometimes participation in an arbitration proceeding is mandatory. Mandatory arbitration results when disputes arise out of a legally binding contract in which the parties agreed to submit to mandatory arbitration. Arbitration is also mandatory when state law requires parties to enter into mandatory arbitration.

Although perhaps not obvious, federal law lies at the heart of mandatory arbitration clauses in contracts. Specifically, Congress enacted the Federal Arbitration Act (FAA) through its Commerce Clause powers. This act requires parties to engage in arbitration when those parties have entered into legally binding contracts with a mandatory arbitration clause, providing the subject of those contracts involves commerce. In Southland Park v. Keating, the U.S. Supreme Court interpreted this federal statute to apply to matters of both federal and state court jurisdiction. Indeed, the Court held that the FAA created a national policy in favor of arbitration. It also held that the FAA preempts state power to create a judicial forum for disputes arising under contracts with mandatory arbitration clauses. In a later decision, the Court held that the FAA encompasses transactions within the broadest permissible exercise of congressional power under the Commerce Clause. This means that the FAA requires mandatory arbitration clauses to be enforceable for virtually any transaction involving interstate commerce, very broadly construed.

Some states require mandatory arbitration for certain types of disputes. For instance, in Oregon, the state courts require mandatory arbitration for civil suits where the prayer for damages is less than $50,000, excluding attorney fees and costs. Many parties accept the arbitration award without appeal. However, when state law requires mandatory arbitration of certain types of disputes, parties are permitted to appeal because the arbitration is nonbinding. In nonbinding arbitration, the parties may choose to resolve their dispute through litigation if the arbitration award is rejected by a party. However, some states have statutory requirements that, in practice, create a chilling effect on appealing an arbitration award. For example, in the state of Washington, if the appealing party from a nonbinding mandatory arbitration does not do better at trial than the original award issued by the arbitrator, then that party will incur liability not only for its own expenses but also for those of the opposing side. In nonbinding arbitration, this is a powerful incentive for parties to accept the arbitration award without appealing to the judicial system.

In New Jersey, by rule of court, nonbinding arbitration is mandatory for civil cases involving automobile negligence, personal injury, contracts and commercial matters. In addition, some insurance matters must be submitted to nonbinding arbitration as well. Like the situation in Oregon above, if either party chooses to reject the arbitration award, the case can then proceed to trial.

Voluntary arbitration also exists, and it is frequently used in business disputes. Sometimes parties simply agree that they do not want to litigate a dispute because they believe that the benefits of arbitration outweigh the costs of litigation, so they choose voluntary arbitration in hopes of a speedy and relatively inexpensive and private outcome. Other times, parties are not certain how strong their case is. In such cases, arbitration can seem much more attractive than litigation.

Arbitration awards can be binding or nonbinding. Some states, like Washington State, have codified the rule that arbitration decisions are binding when parties voluntary submit to the arbitration procedure. In binding arbitration, the arbitration award is final; therefore, appealing an arbitration award to the judicial system is not available. In many states, an arbitration awards is converted to a judgment by the court, thereby creating the legal mechanism through which the judgment holder can pursue collection activities. This process, called confirmation, is contemplated by the FAA and often included in arbitration agreements. But even if the FAA does not apply, most states have enacted versions of either the Uniform Arbitration Act or the Revised Uniform Arbitration Act. These state laws allow confirmation of arbitration awards into judgments as well.

In the tent example, the tent manufacturer and the fabric supplier could agree to submit their dispute to voluntary arbitration. Since they are deciding to go to arbitration in lieu of litigation, they will most likely elect for the decision of the arbitrator to be binding. They would mostly likely select an arbitrator that has expertise in the fabric industry and will agree on the procedures and rules that will govern the arbitration process. During the arbitration, the arbitrator would review the evidence presented by both parties, including any independent testing of the fabric, and make a decision on whether the supplier provided water-resistant fabric or not. The arbitrator would then decide whether the supplier is entitled to payment for the fabric and, if so, the amount owed. If the parties agreed to make the arbitration binding, there would be no appeal of the arbitrator’s decision. However, if the parties elected non-binding arbitration, either of the parties that was unhappy with the award could appeal to the appropriate court.

Like any other form of dispute resolution, arbitration has certain benefits and drawbacks. Arbitration is an adversarial process like a trial, and it will produce a “winner” and a “loser.” Arbitration is more formal than negotiation and mediation and, in many ways, it resembles a trial. Parties present their cases to the arbitrator by introducing evidence. After both sides have presented their cases, the arbitrator issues an arbitration award.

Rules related to arbitration differ by state. The rules of procedure that apply to litigation in a trial do not typically apply to arbitration. Specifically, the rules are often less formal or less restrictive on the presentation of evidence and the arbitration procedure. Arbitrators decide which evidence to allow, and they are not required to follow precedents or to provide their reasoning in the final award. In short, arbitrations adhere to rules, but those rules are not the same as rules of procedure for litigation. Regardless of which rules are followed, arbitrations proceed under a set of external rules known to all parties involved in any given arbitration.

Arbitration can be more expensive than negotiation or mediation, but it is often less expensive than litigation. In Circuit City Stores Inc. v. Adams, the U.S. Supreme Court noted that avoiding the cost of litigation was a real benefit of arbitration. The costly discovery phase of a trial is nonexistent or sharply reduced in arbitration. However, arbitration is not necessarily inexpensive. Parties must bear the costs of the arbitrator, and they typically retain counsel to represent them. Additionally, in mandatory arbitration clause cases, the arbitration may be required to take place in a distant city from one of the parties. This means that the party will have to pay travel costs and associated expenses during the arbitration proceeding. The Circuit City Court also noted that mandatory arbitration clauses avoid difficult choice-of-law problems that litigants often face, particularly in employment law cases.

Arbitration is faster than litigation, but it is not as private as negotiation or mediation. Unlike mediators, arbitrators are often subject-matter experts in the legal area of dispute. However, as is true for mediators, much depends on the arbitrator’s skill and judgment.

A common issue that arises is whether mandatory arbitration is fair in certain circumstances. It’s easy to imagine that arbitration is fair when both parties are equally situated. For example, business-to-business (B2B) arbitrations are often perceived as fair, especially if businesses are roughly the same size or have roughly equal bargaining power. This is because they will be able to devote approximately the same amount of resources to a dispute resolution, and they both understand the subject under dispute, whatever the commercial issue may be. Moreover, in B2B disputes, the subjects of disputes are commercial issues, which may not implicate deeper social and ethical questions. For example, contract disputes between businesses might involve whether goods are conforming goods or nonconforming goods under the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC). No powerful social or ethical questions arise in such disputes. Indeed, resolving such disputes might be seen as “business as usual” to many commercial enterprises.

However, issues of fairness often arise in business to employee (B2E) and business to consumer (B2C) situations, particularly where parties with unequal bargaining power have entered into a contract that contains a mandatory arbitration clause. In such cases, the weaker party has no real negotiating power to modify or to delete the mandatory arbitration clause, so that party is required to agree to such a clause if it wants to engage in certain types of transactions. For example, almost all credit card contracts contain mandatory arbitration clauses. This means that if a consumer wishes to have a credit card account, he will agree to waive his constitutional rights to a trial by signing the credit card contract. As we know, the FAA will require parties to adhere to the mandatory arbitration agreed to in such a contract, in the event that a dispute arises under that contract. In such cases, questions regarding whether consent was actually given may legitimately be raised. However, the U.S. Supreme Court has held that in B2E contexts, unequal bargaining power alone is not a sufficient reason to hold that arbitration agreements are unenforceable, and it is not sufficient to preclude arbitration.

Additionally, concerns about fairness do not end at contract formation. If a dispute arises and mandatory arbitration is commenced, the unequal power between parties will continue to be an important issue. In the case between a credit card company and an average consumer debtor, the credit card company would clearly be in a more powerful position vis-à-vis the debtor by virtue of the company’s financial strength and all that comes with it, such as experienced attorneys on staff, dispute-resolution experience, and contractual terms that favor it, rather than the consumer debtor. In such cases, if the consumer debtor is the aggrieved party, he may very well decide to drop the matter, especially if the arbitration clause requires arbitration proceedings to occur in a distant city. The credit card company will have vast financial resources as compared to the consumer debtor. Moreover, in this example the credit card company’s legal counsel will know how to navigate the arbitration process and will have experience in dispute resolution, processes that often confound people who are not trained in law. Additionally, the list of arbitrators may include people who are dependent on repeat business from the credit card company for their own livelihoods, thereby creating—or at least suggesting—an inherent conflict of interest. Many mandatory arbitration clauses create binding awards on one party while reserving the right to bring a claim in court to the other party. That is, a mandatory arbitration clause may allow the credit card company to appeal an arbitrator’s award but to render an award binding on the consumer debtor. Obviously, this would allow the credit card company to appeal an unfavorable ruling, while requiring the consumer debtor to abide by an arbitrator’s unfavorable ruling. To a consumer debtor, the arbitration experience can seem like a game played on the credit card company’s home court—daunting, feckless, and intimidating.

Additionally, some types of disputes that have been subjected to mandatory arbitration raise serious questions about the appropriateness of ADR, due to the nature of the underlying dispute. For example, in some recent B2E disputes, claims relating to sexual assault have been subjected to mandatory arbitration when the employee signed an employment contract with a mandatory arbitration clause. Tracy Barker, for example, was reportedly sexually assaulted by a State Department employee in Iraq while she was employed as a civilian contractor by KBR Inc., a former Halliburton subsidiary. When she tried to bring her claim in court, the judge dismissed the claim, citing the mandatory arbitration clause in her employment contract. After arbitration, she won a three-million-dollar arbitration award. As KBR Inc. noted, this “decision validates what KBR has maintained all along; that the arbitration process is truly neutral and works in the best interest of the parties involved.” Despite this statement, KBR Inc. has filed a motion to modify the award.

In a similar case, employee Jamie Leigh Jones worked for KBR Inc. in Iraq when she was drugged and gang raped. She was initially prohibited from suing KBR Inc. in court because her employment contract contained a mandatory arbitration clause. However, when considering this case, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that sexual assault cases may, in fact, be brought in court rather than being subjected to mandatory arbitration, despite the contract language requiring mandatory arbitration. Jones’s claims were beyond the scope of the arbitration clause, because sexual assault is not within the scope of employment.

Cases like these have brought public attention to the question of fairness in the use of arbitration clauses, and some states have made recent changes to laws in this area.

In part as a reaction to these types of cases, the Ending Forced Arbitration of Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment Act of 2021 was signed into law in 2022 by President Joe Biden. This Act amends the FAA and give employees with arbitration agreements with their employers the option of bringing claims of sexual assault or sexual harassment either in arbitration or in court.

In B2C cases, different issues of fairness exist. As noted previously, when the parties possess unequal power, these issues can be magnified. Public Citizen, a nonprofit organization that represents consumer interests in Congress, released a report concerning arbitration in B2C disputes. Specifically, the report argued that arbitration is unfair to consumers in B2C disputes and that consumers fare better in litigation than in arbitration. According to the report, incentives exist to favor businesses over consumers in the arbitration process. It pointed to the lack of appeal rights, lack of requirement to follow precedents or established law, limits on consumers’ remedies, prohibitions against class-action suits, limitations on access to jury trials, limitations on abilities to collect evidence, and greater expense as additional factors speaking to the unfairness of arbitration over litigation in B2C disputes.

Importantly, and despite the FAA’s broad interpretation, not all binding arbitration clauses have been upheld by courts in B2C cases. In 2007, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that AT&T’s binding arbitration clause for wireless customers is unenforceable under California state law. The court further noted that the relevant state law is not preempted by the FAA, because the FAA does not prevent the courts from applying state law. In this case, that law involved unconscionability of contract terms. As noted previously, the FAA requires parties to submit to mandatory arbitration when they agree to do so in a legally binding contract, and it preempts state powers to provide a judicial forum in those matters. However, the Ninth Circuit’s holding in this case underscores the fact that state contract law is not circumvented by the federal statute.

Arbitration is a widely used form of ADR, but important questions have been raised about its appropriateness in certain types of disputes. Before signing a mandatory arbitration agreement, it’s important to realize that under current law, your opportunity to bring your claim in court will be severely restricted or entirely precluded. Moreover, if you sign such an agreement with a party who holds inherently greater power than you, such as your employer, then you may find yourself at an extreme disadvantage in an arbitration proceeding.

Activity 3B

What’s Your Verdict?

3.5 Other Methods of Alternative Dispute Resolution

Remember that ADR is a broad term used to denote methods of resolving disputes outside of litigation. This can really be any method, whether or not it bears a specific label or adheres to a particular procedure. For instance, negotiation might be a quick meeting in the hallway between parties, or it might involve a formal round of negotiations where all parties are represented by legal counsel.

However, when parties are attempting to resolve a dispute, it makes sense for them to agree to a specific procedure beforehand, so that each party understands how to proceed. Negotiation, mediation, and arbitration are the most common forms of ADR. However, these methods might not be appropriate for every dispute. Other forms of ADR exist, ranging from in-house programs to very formal external processes. This section briefly discusses commonly used alternatives to resolving disputes besides negotiation, mediation, arbitration, or litigation.

Some ADR processes or programs are available only to certain groups of people, such as members of a particular organization. For instance, some organizations, like Boeing, have an internal ethics hotline. This hotline is available for employees to report perceived ethics violations that they have observed. Ethics advisors answer employees’ questions and follow up on reports that need further investigation. One major benefit of this method is that reporting parties generally (but not always) remain anonymous. Another benefit is that the company has time to redress problems that could give rise to disputes of much greater magnitude if left unaddressed.

An open-door policy is an in-house program that allows company employees to go directly to any level of management to file a complaint or grievance, without threat of retaliation for their reporting. In theory, this policy creates an open atmosphere of trust, and it breaks down class barriers between groups of employees. However, many employees may not feel comfortable in making a complaint about a manager’s decision. Moreover, supervisors may not be comfortable with their employees bypassing them to file complaints. Open-door policies sound very good in theory, but they may not work as well in practice.

Another type of in-house program is an ombudsmen’s office. These stations generally hear complaints from stakeholders, such as employees or customers. Ombudsmen try to troubleshoot these complaints by investigating and attempting to resolve the issues before they escalate into more formal complaints.

More formal methods of ADR include mediation-arbitration (med-arb), which is essentially a mediation followed by an arbitration. If the mediation does not produce a satisfactory outcome, then the parties submit to arbitration. The neutral party mediating the dispute also serves as the arbitrator if the dispute-resolution process goes that far. Med-arb has the same benefits and drawbacks as mediation and arbitration separately, with some important differences. For instance, parties in a med-arb know that their dispute will be resolved. This is unlike mediation alone, where parties may walk away if they do not think that the mediation is serving their interests. Moreover, the parties in med-arb have an opportunity to reach a win-win outcome as in mediation. However, if they do not reach a satisfactory outcome, then one party will “win” and one party will “lose” during the arbitration phase. The knowledge that an arbitration will definitely follow a failed mediation can be a strong incentive to ensure that the mediation phase of a med-arb works.

Private judging, contemplated by many state statutes, is a process in which active or retired judges may be hired for private trials. Private judging is essentially private litigation. The hired judge can preside over a private trial that is not truncated by limits on discovery or abbreviated rules of procedure, as would be the case in arbitration. Additionally, the judge who oversees the process is highly experienced in such matters as evidence and decision rendering. Moreover, the parties who can afford to pay for this service have a substantial benefit in not having to wait to have their cases heard in the public court. The private trial is also private rather than public, which may be important to parties who require confidentiality. In states where statutes permit hiring a judge for such matters, the parties’ ability to appeal is often preserved. Drawbacks include the sometimes-questionable nature of enforceability of judgments rendered, though some state statutes allow enforceability of those judgments as if they were issued in public court. Moreover, this system may benefit those who can afford to pay for this service, while others must wait for their case to appear on the docket in public court. This raises questions of fairness.

A minitrial is a procedure that allows the parties to present their case to decision makers on both sides of the dispute, following discovery. This is a private affair. After the cases are presented, the parties enter into mediation or negotiation to resolve their dispute.

A summary jury trial is a mock trial presented to a jury whose verdict is nonbinding. The presentation is brief and succinct, and it follows a discovery period. The jury does not know that its verdict will be advisory only. This process allows parties to measure the strengths and weaknesses of their cases prior to engaging in litigation, which presumably saves both time and money. After the minitrial, parties are in a better position to negotiate or mediate an outcome that fairly represents their positions.

3.6 Public Policy, Legislation, and Alternative Dispute Resolution

Alternative dispute resolution can be a very useful alternative to litigation. There are many advantages to parties, such as expediency, cost savings, and greater privacy than litigation. In business-to-business (B2B) disputes, alternative dispute resolution (ADR) often makes sense.

The Federal Arbitration Act (FAA) is a federal statute that the U.S. Supreme Court interpreted as a national policy favoring arbitration in Southland Corp. v. Keating. According to the Southland Corp Court, state power to create judicial forums to resolve claims when contracting parties enter into a mandatory arbitration agreement has been preempted by the FAA. However, not all disputes are well suited for ADR. This is an area in which Congress could make substantial changes in public policy through the creation of new law to ensure fairness between unequal parties and to ensure the protection of civil rights. Congress could do this by making ADR optional, rather than mandatory, for some types of disputes. It could also exclude certain types of disputes from being bound to arbitration through mandatory arbitration clauses.

For example, the proposed Arbitration Fairness Act of 2009 (AFA) would invalidate mandatory arbitration clauses in employment and consumer disputes, as well as in disputes arising from civil rights violations. The AFA is a proposed bill to amend the FAA. Under the Commerce Clause, Congress has the power to limit the use of mandatory arbitration, just as it has the power to enforce mandatory arbitration clauses under the Commerce Clause through the existing FAA. By passing a new law that excludes certain types of disputes from being subjected to mandatory arbitration, Congress could set new policy regarding fairness in dispute resolution. Likewise, if it fails to act, Congress is also acceding to the U.S. Supreme Court’s broad interpretation of the FAA as a national policy favoring arbitration. Either way, policy regarding mandatory arbitration exists, and Congress has a central role in defining that policy. Recent Congresses have considered many Bills that would create more options and choice surrounding arbitration under the FAA, but thus far they have failed to receive enough votes to make it to the President’s desk for a signature.

In 1925, when the FAA was originally passed, records indicate that Congress intended that mandatory arbitration clauses be enforced in contracts between merchants, rather than between businesses and consumers or between employers and employees. In the latter relationships, the parties have vastly unequal power. Moreover, despite the existence of mandatory arbitration clauses in contracts, the FAA was not contemplated as a means to preempt state power to provide judicial forums for certain types of disputes. However, the U.S. Supreme Court has greatly expanded the FAA’s applicability since then.

If Congress passed the AFA, this would be an example of one branch of government “checking” another branch’s power as contemplated by the U.S. Constitution. Specifically, the legislative branch would be checking the judicial branch’s power by passing a law to counteract the U.S. Supreme Court’s broad interpretation of the FAA in Southland Corp. v. Keating.

This is how our government is supposed to work. One branch checks another branch’s power. This “checking” of power maintains relative balance among the branches. Because people have different points of entry into the lawmaking process, this system ultimately balances the many special interests of the American people. For example, some businesses and employers that do not wish the AFA to pass may wonder what recourse they have. After all, the U.S. Supreme Court’s interpretation of the FAA currently favors their interests. Since the AFA has not yet passed, they could lobby lawmakers against its passage. Note too that if the AFA becomes law, these interest groups are not simply shut out of the government’s lawmaking process. They continue to have access to lawmaking. One point of entry is through the legislative branch. For instance, they could return to Congress and ask it to pass a new law to counteract the AFA, or to repeal the AFA altogether. They also have a point of entry to the lawmaking process through the judicial branch. Specifically, once a case or controversy arose under the AFA in which they had standing, they could ask the courts to interpret the statute narrowly, or they could ask the courts to strike down the statute altogether.

On the other side of the issue, consumers and employees who do not like the FAA’s current broad interpretation can work within our government system to change the law. For instance, they can ask Congress to pass a new law, such as the AFA. They could ask Congress to repeal the FAA. They could also wait for another case to arise under the FAA to try to get the relevant holding in the Southland Corp. case overturned. This is perhaps more difficult than the first two options, because any U.S. Supreme Court case produces many progeny at the circuit court level. Each decision at the circuit court level also produces binding precedent within that jurisdiction. It is very difficult to get a case before the U.S. Supreme Court. Even if that happened, there would be no guarantee that the Court would overturn a prior opinion. In fact, the opposite is usually true. Precedent is most often followed rather than overturned.

In the United States, the policy process is open for participation, though changes often take much work and time. People with special interests tend to coalesce and press for changes in the law to reflect those positions. This appears to be what is happening in the world of ADR now. After many years of mandatory arbitration requirements that have yielded perhaps unfair processes or results, groups that believe they should not be forced into ADR by mandatory arbitration clauses are building momentum for their position in Congress. If the AFA passes, that will not be the end of the story, however. New interest groups may form to support the previous law, or a new law altogether.

Activity 3C

Debate: Unbinding Arbitration

Randall Fris was employed by Exxon Shipping Company as an able-bodied seaman on an oil tanker called the Exxon Long Beach. Fris worked under a union agreement that required arbitration of employment disputes. Exxon had a policy against working under the influence of drugs or alcohol on its tankers, and the agreement with the union provided for the use of a breathalyzer test ‘for cause’ with a Blood Alcohol Content (BAC) of .04 or above considered intoxicated for purposes of working on an Exxon tanker. The agreement stated that the penalty for such intoxication “… may result in discharge from the vessel and subject the employee to further discipline up to and including termination.” Around midnight one night, Fris reported for duty on the tanker appearing to several officers to be intoxicated. A breathalyzer was administered and resulting in a BAC of .15. The next day, Exxon Shipping discharged Fris, and the union filed a grievance. The grievance was submitted to a panel of arbitrators and after a hearing, the panel found that Fris should be reinstated to his position, stating that the policy did not require dismissal, and considering the totality of the circumstances, including the length of employment and Fris’ good record, termination was not the appropriate remedy.

Question: As a rule, arbitration is mandatory and binding and cannot be appealed. What does this mean for a case like the Exxon Shipping case?

Question: Would you be in favor of a law that prevented arbitrations from being binding in certain situation? What situations?

Question: Should Exxon Shipping be able to appeal this decision even though the arbitration clause in the union agreement is for binding arbitration?

Debate the Case: Find and review a source of information on the benefits and drawbacks of binding arbitration. If arbitration was non-binding would this change the utility of this type of alternative dispute resolution? Would arbitration still be a valuable alternative to litigation?

- What are the benefits of negotiation as a dispute-resolution method? What are the drawbacks?

- How can parties that have unequal bargaining power negotiate meaningfully, without one party taking advantage of the other? Have you ever negotiated with someone who had more bargaining power than you? What were your strategies during the negotiation? Did you obtain your goal by the conclusion of the negotiation?

- Identify a situation in which you would choose mediation as your preferred method of dispute resolution. Why is mediation the best method in this situation? What are the potential benefits and drawbacks of mediation in this situation?

- Should mediators be required to be licensed, like attorneys or physicians, before practicing? Why or why not?

- Bank of America announced that it would no longer require mandatory arbitration in disputes arising between it and consumer credit card account holders. Review the story here: http://www.reuters.com/article/idUSTRE57D03E20090814. What are the benefits and drawbacks to Bank of America’s credit card account customers with respect to this change?

- In what contexts have you entered into an arbitration agreement (e.g., home purchase, credit card agreement, cell phone agreement)? Write a short essay discussing the implications of entering into that agreement.

- Locate two “ethics hotline” programs from an online search. Compare these programs. What are the benefits and drawbacks to each?

References

9 U.S.C. §1 et seq.

Circuit City Stores, Inc., v. Adams, 532 U.S. 105 (2001).

Citizens Bank v. Alafabco, Inc., 539 U.S. 52 (2003).

Exxon Shipping Co. v. Exxon Seamen’s Union, 11 F.3d 1189 (3d Cir. 1993)

Gilmer v. Interstate/Johnson Lane Corp., 500 U.S. 20 (1991).

Jones v. Halliburton Co., 583 F.3d 228 (5th Cir. 2009).

Juan A. Lozano, “Woman Awarded $3M in Assault Claim against KBR,” AP News, November 19, 2009

Lozano v. AT & T Wireless, 504 F.3d 718 (9th Cir. 2007).

Margaret L. Moses, Statutory Misconstruction: How the Supreme Court Created a Federal Arbitration Law Never Enacted by Congress, 34 Fla. St. U.L. Rev. 99 (2006).

New Jersey Court Rule 4:21A

ORS 36.405.

Roger Fisher, William Ury, and Bruce Patton, Getting to Yes (New York: Penguin Books, 1991), 100.

Southland Corp. v. Keating, 465 U.S. 1 (1984).

Uniform Arbitration Act, RCW 7.04.

Washington State Court Rules of Procedure, Superior Court Mandatory Arbitration Rules 7.3.

a catchall term that describes a variety of methods that parties can use to resolve disputes outside of court, including negotiation, conciliation, mediation, collaborative practice, and the many types of arbitration

an out-of-court procedure for resolving disputes in which one or more people -- the arbitrator(s) -- hear evidence and make a decision

a give-and-take discussion that attempts to reach an agreement or settle a dispute

a process that involves opposing parties in a dispute meeting with a neutral third party (called the "mediator") who helps them negotiate a resolution outside of court

a procedure that allows the parties to present their case to decision makers on both sides of the dispute, following discovery

a mediation followed by an arbitration when the mediation does not produce a satisfactory outcome

a federal statute under which parties are required to participate in arbitration when they have agreed by contract to do so, even in state court matters

mandatory referral of a certain class of civil suits to an arbitration hearing

a sector of business activity that focuses on commerce performed between businesses

a person who conducts mediations as a neutral third party to work with parties in dispute and try to reach a resolution

1) The written decision of an arbitrator or commissioner (or any nonjudicial arbiter) setting out the arbitrator's award. 2) The amount awarded in a money judgment to a party to a lawsuit, arbitration, or administrative claim

individual, often an expert in the law and subject matter at issue, who presides over arbitration proceedings

a transaction between a business and its employee

a transaction that takes place between a business and an individual as the end customer

a process in which active or retired judges may be hired for private trials

government policies that affect the whole population